“Houston, Tranquility Base here. The Eagle has landed.”

Fifty years ago this month, those immortal words from Apollo 11 astronaut Neil Armstrong were heard by hundreds of millions of awestruck earthlings, roughly 240,000 miles away. And they echoed throughout human history.

Since the beginning of homo-sapiens, man has looked up to the night sky and mused about the pure white light from the Moon. It’s periodically changing shape and brightness has long-fascinated hunters, farmers, and gatherers. Its regular monthly cycle became the first clock by which humans measured the passage of time. Certain aspects of the lunar cycle steadfastly marked the arrival of special activities, such as the start of harvest season. The gravitational pull of the Moon on our oceans creates tides, by which ancient mariners would schedule their voyages. Occasionally, it almost looks as if one could touch it. In some ways, the Moon has become an extension of the human psyche, like the mountains and oceans here on Earth.

The study of celestial objects, astronomy, is the oldest of our recognized sciences. World famous scientists, such as Galileo and Kepler, improved crude telescopes so they could view the Moon more intimately and study its various mountains, craters, and plains in detail. The invention of the telescope greatly expanded the human study of the cosmos.

But, our Moon, remained vexingly beyond our physical grasp…

That is, until the Cold War, when rocket technology was in its formative stages. The Soviet Union and the United States decided that space was both a strategic national security frontier and an ideal environment in which to showcase technological superiority to the rest of the world. The Soviets staked the first claim in October 1957 by placing a small satellite called Sputnik into orbit around the Earth.

The first man-made object to reach the Moon was also Soviet—the unmanned probe Luna 2, which was purposefully crashed on the Moon’s surface in September 1959. This was followed by numerous probes from both the Soviet Union and the United States doing flybys, orbits, and controlled crashes with many failures along the way.

On May 25, 1961, President John F. Kennedy ignited a dramatic expansion of the great Moon race of the 1960s. In a televised speech to Congress, he proposed the U.S. “should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to the Earth.”

Both the Soviet and U.S. space agencies had been focusing their efforts on unmanned probes and robot landers. Now the entire game had changed—humans were going to the Moon instead!

Finally, in February 1966, the USSR unmanned Luna 9 successfully made the first soft landing on the Moon and transmitted photographic data back to Earth. Four months later, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s (NASA) unmanned Surveyor 1 made the first U.S. soft landing and gathered data about the lunar surface for the upcoming Apollo landings.

For various reasons, the U.S.S.R. manned spaceflight program then ran into many rocket delays and launch failures, although their unmanned programs kept moving forward.

After two NASA lunar orbital flights—Apollo 8, in December, 1968, and Apollo 10, in May, 1969—the entire world anxiously anticipated the flight of Apollo 11.

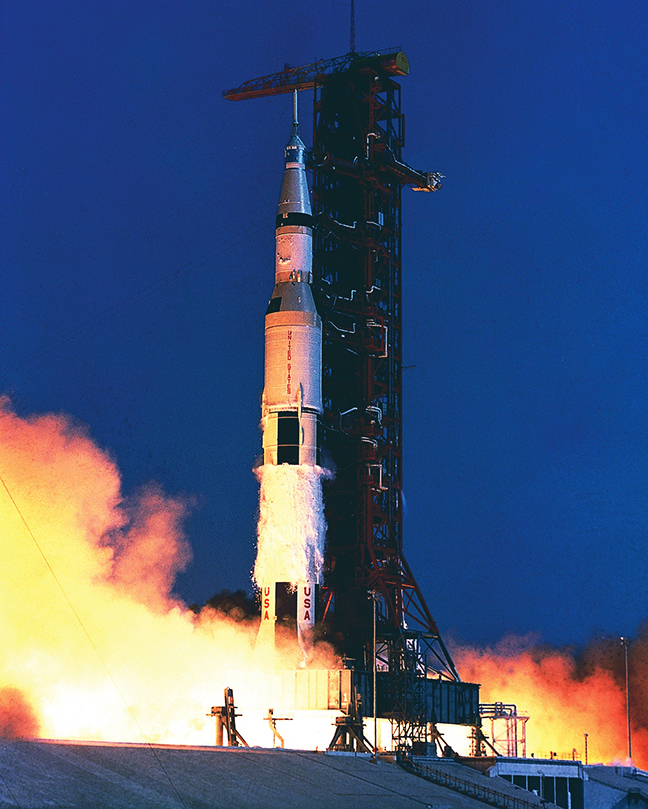

On July 16, 1969, a mighty Saturn V rocket launched the Apollo 11 mission from Kennedy Space Center with three astronauts inside the command module. The Mission Commander was Neil Armstrong, the Lunar Module Pilot was Buzz Aldrin, and the Command Module Pilot was Michael Collins.

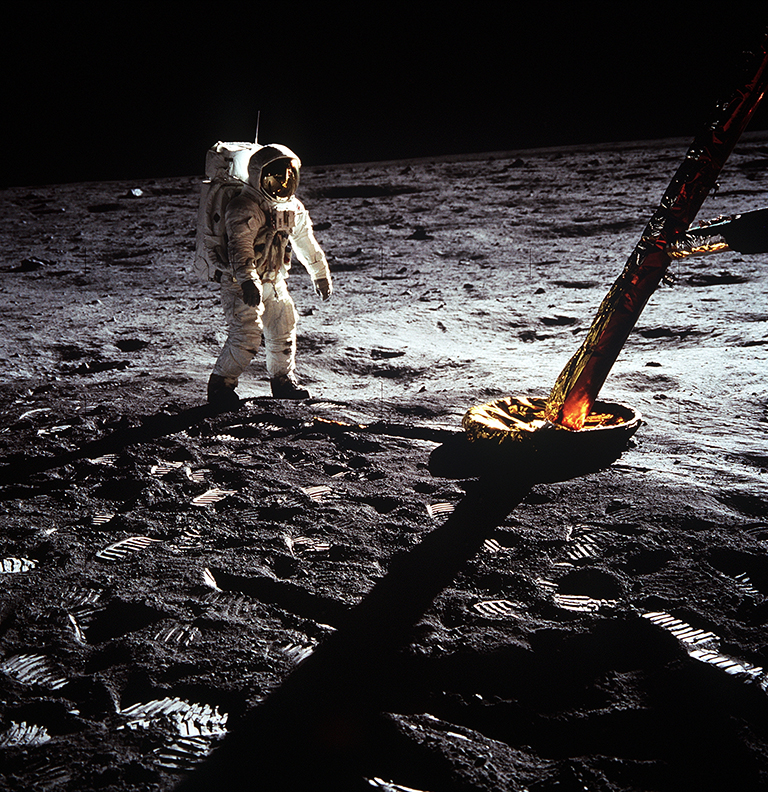

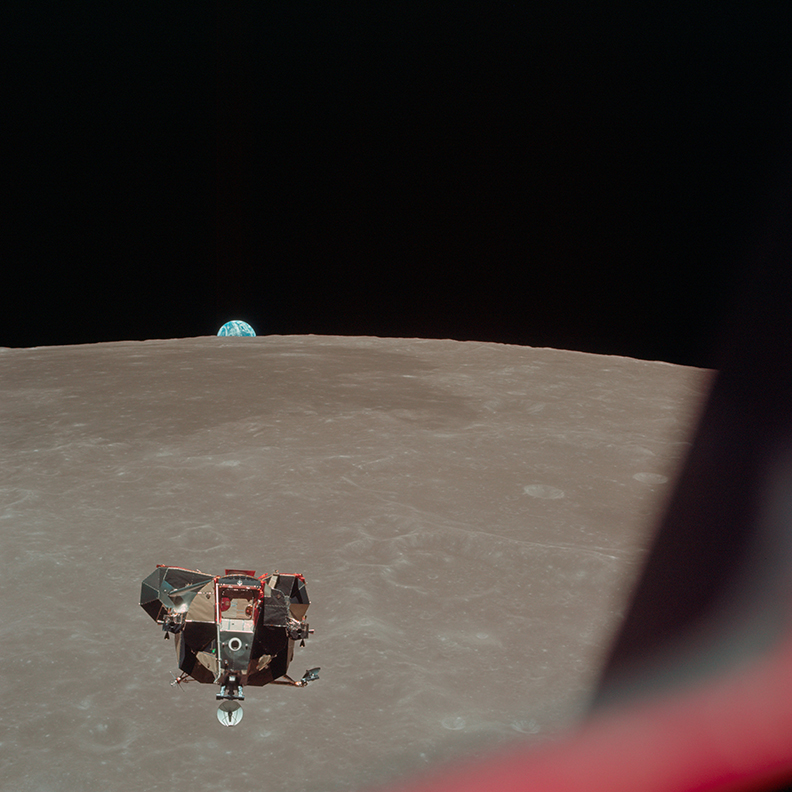

Following a three-day translunar flight, the command module Columbia was guided into lunar orbit. After several hours, the lunar module Eagle separated from the main spacecraft with Armstrong and Aldrin inside, and descended to the Moon’s surface. The LM was the very first true spacecraft, designed to fly in the vacuum of space, not in Earth’s atmosphere.

The Eagle landed very near to the planned target point in the Sea of Tranquility. That’s when Armstrong radioed to NASA mission control in Houston “The Eagle has landed.” Hundreds of millions of TV viewers were momentarily “welded together as one mind” in the collective awe of having a human finally being on the surface of the Moon.

After a few hours of rest, both astronauts dressed in their space suits. Armstrong exited the LM first, slowly descending a ladder. After making the three-foot jump from the bottom step to the Moon’s surface he uttered “That’s one small step for a man, one giant leap for mankind.”

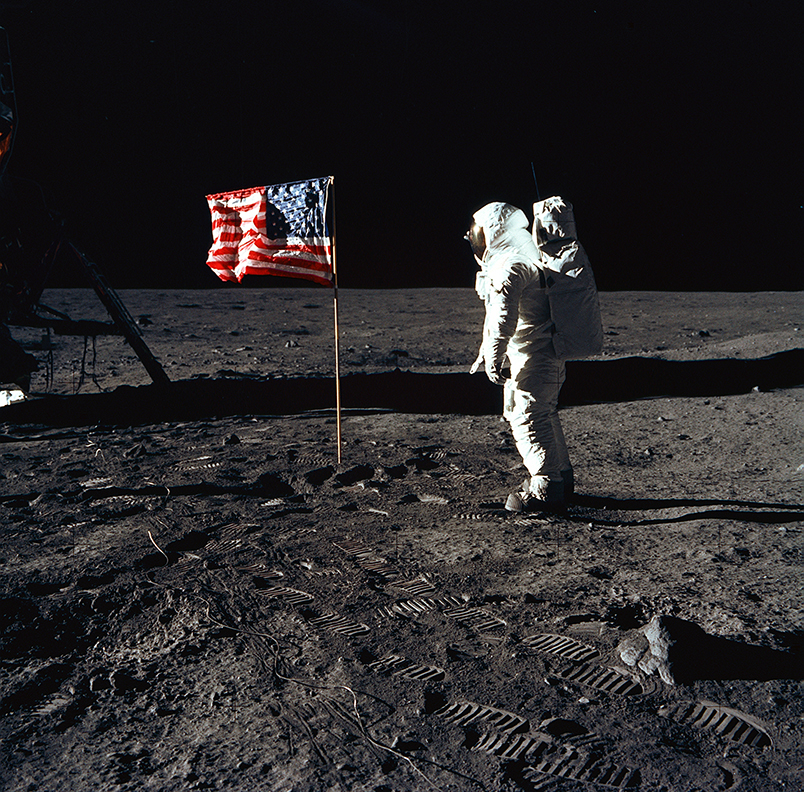

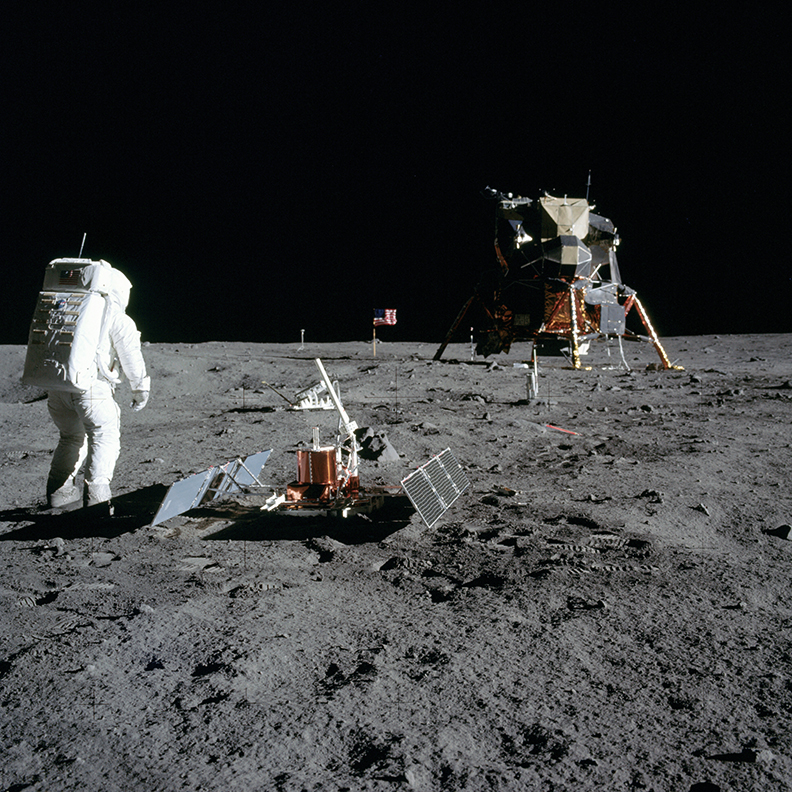

Twenty minutes later, Aldrin carefully crawled across the “porch” of the LM and descended the ladder to join Armstrong on the surface. During their moonwalk of two and a half hours, they set up several experiments, planted an American flag, collected Moon rocks and soil samples, took many photographs, and provided verbal descriptions of surface features. Most of this activity was watched on live black and white TV back on Earth.

When the lunar surface Extra Vehicular Activity (EVA) plan had been completed, they re-entered the LM with 48 pounds of lunar rocks (Earth weight) and prepared to blast off to rendezvous with Collins, who had orbited the Moon alone 25 times in the command module Columbia.

A few hours later, all the three astronauts were together again and their spacecraft headed back to Earth using a gravity-assisted return trajectory.

On July 24, the spacecraft splashed down in the Pacific Ocean near Johnston Island. The WWII-era aircraft carrier USS Hornet (CVS-12) flawlessly recovered the spacecraft and its three-man crew. Using a formal NASA quarantine protocol to prevent potential moon germs from getting into the Earth’s biosphere, the astronauts exited their spacecraft wearing special biological isolation garments. The outside of these suits were then wiped down by a Navy UDT swimmer using a bleach solution.

After being flown back to the Hornet by helicopter, the astronauts were ensconced in a unique NASA trailer called a Mobile Quarantine Facility (MQF) where they changed into flight suits. An hour later, from inside the MQF, the three astronauts chatted with President Richard Nixon who welcomed them back to Earth. This was the only time a President had ever been physically present for a spacecraft recovery at sea. The ceremony was broadcast live to 500 million TV viewers worldwide!

The Apollo 11 lunar landing mission is considered the greatest scientific achievement in the history of mankind. While earthlings will inevitably go back to the Moon and on to Mars and beyond, we will forever be standing on the shoulders of the vast Apollo program team. This is estimated to have consisted of 400,000 people – NASA employees, university professors and students, commercial contractors and parts suppliers—not to mention the American taxpayers who footed the $25 billion cost!

From July 16 to 24, the USS Hornet Sea, Air and Space Museum will be joining the Smithsonian Institution, NASA, the Navy and other organizations in commemorating the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 mission. More information about the public Splashdown 50 event can be found at https://uss-hornet.org/splashdown50

Leave a Reply