The Mona Lisa, Leonardo Da Vinci’s iconic painting wasn’t always as famous as she is now. Prior to Vincenzo Peruggia ripping her off the wall in the Louvre in August 1911, she was just another pretty face.

My longtime affinity for Mona Lisa goes back to childhood; my mother always displayed her image, and my girlish heart soared when Nat King Cole crooned the Mona Lisa song from cafe jukeboxes. Imagine the thrill when I met Ray Evans who wrote the “Mona Lisa” song. Giddy as a schoolgirl, I asked about his 1950s megahit. “It’s my best money-maker; I still get royalties in my mailbox.” Evans told me and sang the first line. “Mona Lisa, Mona Lisa men have named you…”

When I further researched “the lady with the mystic smile” I learned how she had become the most famous painting on earth. According to my Facebook friend, art historian Professor Noah Charney, he writes about her mysterious back story in his book, The Thefts of Mona Lisa: On Stealing the World’s Most Famous Painting. Professor Charney founded ARCA— Association for Research into Crimes Against Art, a non-profit Rome-based think tank.

The 1911 heist of the Mona Lisa first appeared to have all the marks of an international theft ring, but the artwork was stolen by a nondescript disgruntled museum contractor, Vincenzo Peruggia, who co-workers nicknamed ‘macaroni’.

Peruggia, the unassuming thief from Dumenza in Northern Italy, went to Paris to find work, and was ironically contracted to the Louvre Museum to build a protective glass case for the Mona Lisa. The Louvre, without sufficient alarm systems, was finally beefing up security after Iberian head sculptures had been stolen in 1907 and sold to Picasso. The staff did maintenance on Mondays when the museum was closed.

The Salon Carre, where Mona Lisa was exhibited, also featured Titian, Raphael, Giorgione, Veronese, Tintoretto, Velasquez, Rubens, and Rembrandt masterworks. Peruggia targeted the Mona Lisa, (known as La Giaconda in Italy and La Jocunde in France) because he mistakenly perceived that Napoleon had plundered it along with other Italian treasures during his late 18th century Italian Campaign. Burning with patriotism and a dash of larceny, he believed Da Vinci’s painting should be returned to Italy. Though other Italian paintings were then more valuable, the Mona Lisa was accessible and portable.

Peruggia had spent the previous Sunday night hiding in an airless closet off the staircase while scheming to steal the masterpiece at daybreak. His intention was to return it to the Uffizi in Florence, perhaps with a reward, and hence be acclaimed a national hero.

About 7:30 the morning of 21st August 1911, the white-smocked worker calmly lifted the masterpiece from the protective wall cradle and carried the unwieldy frame to the staircase. There he removed the painted wood panel from the frame, wrapped it in his smock and pried the doorknob off an exit door. It did not open. By chance a worker arrived and unwittingly opened the door. Peruggia nonchalantly carried the treasure under his arm to a museum courtyard and out to the street where he discarded the incriminating doorknob.

Meanwhile, back at the museum, with only a skeleton crew in the low-security 50-acre museum, no one noticed the blank space on the wall until replicator artist Louis Beroud arrived to finish his own copy of La Jocunde. The place where once hung the masterpiece had four pegs in the wall; the painting was missing!

Monsieur Picquet, maintenance director, coolly replied that the painting may have been removed to photograph in better light as was the custom. The earthshattering impact of the daring theft would not be discovered until Tuesday when viewers arrived. Gendarmes rushed in, launched a dragnet around Paris, trains, trolleys and trawlers were stopped. Mon Dieu!

That fateful Monday morning when Vincenzo Peruggia had exited the Louvre unnoticed he hopped a trolley to his flat at 5 Rue de l’Hopital Saint Louis. Carrying the precious loot to his fourth storey room, he placed the Mona Lisa in a firewood cabinet behind his bed, and gloated.

The thief could never have imagined in his wildest dreams that he had succeeded in pulling off the biggest art heist in history, and singlehandedly made the Mona Lisa the world’s most recognizable work of art. Peruggia’s single act of valor, or skullduggery, was to bring fame to the once-incognito Mona Lisa and the then-estimated worth skyrocketed way beyond $5 million.

French detectives jumped on the case, interviewed museum staff, staged roadblocks, newspapers screamed banner headlines, and the frantic hoopla seemed over the top to many. Even though once acclaimed as the “embodiment of the eternal feminine” she was still so obscure that the Washington Post showed an incorrect image with the headline, “Priceless art treasure gone.” Mona who?

So Mona Lisa, once a 16th century nobody, suddenly became an overnight sensation leading to the now-iconic priceless masterpiece drawing over eight million viewers annually to the Louvre.

When news broke that the Louvre’s favourite girl had disappeared gendarmes searched the premises, interrogated workers, fingerprinted everyone. One un-smudged fingerprint was found on the glass cradle, but in 1911 there was an inadequate database. If Peruggia’s print was found he had worked on the display case anyway. The investigation hit a wall, reached a dead end, then the Titanic sank, the Great War loomed, news cycles switched, and the case turned cold.

THE SMILE THAT LAUNCHED A THOUSAND QUIPS

Rumour has it that a police inspector interviewed Peruggia in his flat. During questioning he filled out forms pressing on the actual Mona Lisa panel sitting upside down on the very table where he sat. At least that’s what Peruggia’s daughter Celestina claimed.

The 20-pound painting is small, at only 30” x 21”x 1.5” it was easy to hide. It was not painted on canvas but on a white poplar panel. Peruggia built a wooden crate, placed the cloth-wrapped panel under the false bottom, filled it with clothes, shoes, tools and a mandolin, and secreted the coffin-like box under his bed safe as an unlaid egg.

So Leonardo Da Vinci’s celebrated Mona Lisa, who had already enjoyed over four centuries of public face time, was now demoted to languish in the dark box perhaps alongside a chamber pot under the handyman’s iron bed.

Two years later Peruggia carried the trunk on the train and returned to Italy. He had contacted a Florentine art dealer and offered to sell the precious La Giaconda to the Uffizi Gallery for a piddling 500,000 Lire. The handyman met the potential Uffizi buyers in his modest Tripoli-Italia Hotel room.

They watched as Peruggia removed clothes, shoes, mandolin, and then unceremoniously freed the beloved Mona Lisa from her sarcophagus. Close inspection convinced them the panel was truly Da Vinci’s masterpiece. They carried her to the Uffizi, hearts racing.

Later when the Carabinieri jailed him for grand larceny he was startled. Surely Italy would glorify his patriotism! Lawyers and psychiatrists worked for leniency for the man who claimed to be a patriot. Many Italians, perceiving Peruggia had rightfully returned their beloved Leonardo Da Vinci masterpiece, showered him with praise. Women sent sweet cakes to his cell. “Not so fast,” the law warned.

The Mona Lisa ‘capolavoro’ had never belonged to Italy; Da Vinci had sold it to Francis I, king of France in 1517 when he was court painter. La Giaconda had hung in Fontainebleau, Versailles, and on Emperor Napoleon’s bedroom wall before it went to the Louvre. Italy benefitted from the masterpiece’s brief sojourn, the first in four centuries. When La Giaconda appeared at the Uffizi in Florence it was viewed by over 30,000 people on the first day. Then the kidnapped Mona Lisa caught her last express train from Milano back to Paris.

Vincenzo Peruggia stood trial for the high-profile theft, was diagnosed as mentally deficient owing to the high lead content in paint that he mixed and breathed. Court records showed how his brain was affected by lead poisoning. The verdict was lenient for the ‘patriotic’ thief.

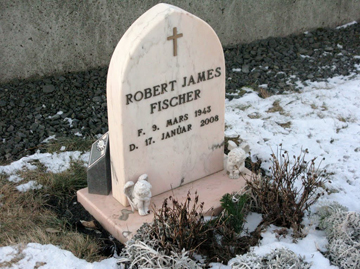

Peruggia served seven months in prison then joined the Italian army during the Great War. After the war he returned to Paris with his wife. Renowned for committing the most celebrated crime of all time, he died in Paris in obscurity on his 44th birthday 8th October 1925.

So the man who had brought recognition to La Giaconda was buried without fanfare, without a gravestone. His notoriety had dissipated, no one cared anymore. But Mona Lisa’s haunting mystique abounded, and the once-unknown Florentine girl with no eyebrows and enigmatic smile, had songs and numerous books written about her.

WHO WAS MONA LISA?

Her name was Lisa Gherardini. born on June 15th 1479. The Florentine girl married merchant Francesco de Giacondo at age 16. Between 1503 and 1507 Lisa sat for a commissioned portrait by Leonardo Da Vinci.

Da Vinci was born April 15th 1452 near the village of Vinci and was schooled in Florence. In 1481 he worked for the Duchy of Sforza as military engineer in Milano where he painted the Last Supper in 1495.

In 1507 King Louis XII named him court painter and he moved to France. King Francois I bought the Mona Lisa in 1516, and when Leonardo died in 1519 the he purchased his entire estate.

Leonardo Da Vinci is celebrated for his body of works; paintings and codex writings made him a Renaissance rock star. Had he not left such detailed legacies he may have just blended in with other great 16th century artists, but his innovations forced him to the top of the artistic pile. The southpaw was not only painter, but engineer, inventor, sculptor, philosopher and all-round genius. Some theorize he invented the helicopter, Scuba gear, perfected siege projectiles and river fording machinery. Scholars theorize that if IQ tests existed Da Vinci would score higher than any other genius.

The introduction of Da Vinci’s sfumato technique gave his art a smoky quality not achieved by others including Michelangelo Buonorotti. He took years to finish a painting because he laid thinned paint with the finest hair brushes, layering in thin coats that toned to monochromatic colours. Lines, borders or heavy strokes evaporated, vanished to subtle graduations of transparency. Every work was a masterpiece.

So to steal one of Leonardo Da Vinci’s masterworks was the coups of all coups. Vincenzo Peruggia was the most daring rogue of the hour, more than just a common thief who courageously succeeded in the heist of a renowned painting from the world’s most prestigious art museum.

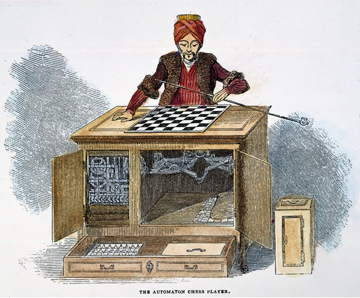

Two decades after the infamous heist the red-hot story still hadn’t died. A bizarre account in the Saturday Evening Post in 1932 has never been proven as either fact or fantasy. Writer Karl Dekker stated he met Argentine aristocrat Valfierno in a bar in Casablanca. Where else? The aristocrat confessed that he had hired master forger Yves Chaudron to paint six fakes of the Mona Lisa that he offered to six different American millionaires for $300,000 each.

Years after the 1911 theft of the Mona Lisa from the Louvre, supposedly by Valfierno’s own gang, he contacted the six unwary potential buyers offering them each the ‘original masterpiece’. The con man said a fake was returned to the Louvre in January 1914, and even if the museum experts had doubted its authenticity, they would not advertise their gross ineptitude. Each rogue connoisseur bought the story, aware of the mother of all heists, and champed at the bit to possess the forbidden work of art for their eyes only.

Though the magazine story purported the ruse to be fact, it was implausible that the simple-minded mastermind Vincenzo Peruggia was ever part of a crime ring.

The Mona Lisa was on the move again during World War II. Fearing the Nazis would plunder the high-value masterpiece; they sequestered it away from Paris by ambulance. Then in 1974, like a wandering Gypsy girl, Mona Lisa went on tour to Tokyo and Moscow.

Time has dulled memories; the incident has faded like the sfumato of a Da Vinci painting, but Peruggia’s family in Dumenza still believe he was a hero. His daughter Celestina and grandchildren Graziella and Silvio Peruggia speak of the daring Mona Lisa snatch with amazement, smile at his audacity. In-depth research has revealed that Vincenzo Peruggia was truly patriotic, albeit he also anticipated a large reward.

Yes, the lady with the mystic smile, and over five centuries of face time has definitely earned her fame. Over the years unstable viewers have thrown coffee cups and red paint at her protective bullet-proof case, but her smile endures. And now you know the rest of Mona Lisa’s story.