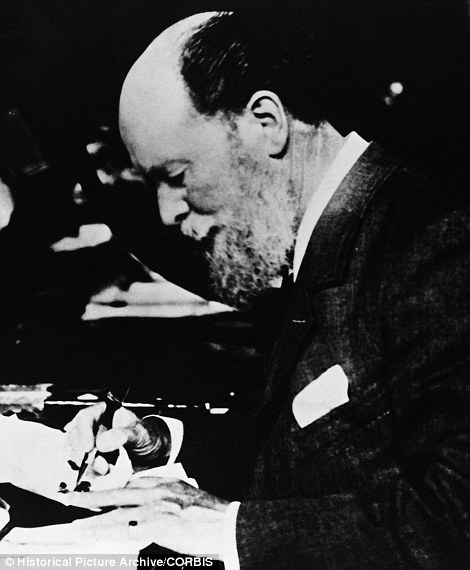

Theo Woodall, an unassuming mild-mannered man, was born in London in 1922. As a youth he enjoyed creating objects and working with his hands, later becoming maker of mechanical components and a master exotic wood turner. He joined the Royal Air Force during World War II and was commissioned to make small airplane components in Egypt.

Years later, in order to hone his skills, Theo restored an 1861 Holtzapffel lathe for precision engineering, manufacture of machine parts and components. After Theo’s life took an unexpected turn, he worked towards more ornamental creations for which he received the turner’s guild recognition as an artist, and later as a credentialed silversmith with his own hallmarks.

In 1969, while driving from a funeral, a family member dropped subtle clues about his ancestry, suggesting he apply for a copy of his birth certificate at the Somerset House Archives. So, at age 47, Theo read his birth registration and was struck by a thunderbolt of twin emotions; a shock that the people who raised him were not his birth parents, and that his real father was Nicholas Faberge, the youngest of five sons of Peter Carl Faberge—Jeweler to the Czar’s Russian Imperial Court.

Few names could strike awe into the heart of an artist as that of the legendary Peter Carl Faberge, master jeweler extraordinaire. Theo Woodall was stunned realizing he was not son of the Woodalls who had raised him, but son of Nicholas Faberge, and grandson of the master craftsman himself—of the fabled House of Faberge.

It became evident by the birth certificate that Theo Woodall, born out of wedlock, was the son of Nicholas Faberge, and grandson of the legendary Peter Carl. And his then eleven year-old daughter Sarah was the great-granddaughter of the fabled jeweler to the Russian Czar.

The Registrar’s Certificate #7888 showed Theo’s birthdate as 26 September 1922, father was Nicholas Faberge, artist-painter, living at 122 Fulham Road, and mother was Dorise Cladish, scholar, 6 Wellington Square. Nicholas’ occupation as artist-painter showed he worked at 76 Fulham Road.

At the time of Theo’s birth in 1922, Nicholas was about 37 and Dorise a tender 17. Rumor has it that the lovers were “desperately in love” according to a relative of Nicholas’ late wife. Research shows that Nicholas Faberge occupied studio #11 at The Avenue on the mews, an avant-garde artist, sculptor and foundry collective, where John Singer Sargent had occupied studios #8, 12 and 14 for over 20 years. In 1893 Charles Edward Halle created the Shaftsbury ‘Eros’ statue at The Avenue and in 1896 James Abbott Whistler had painted in a rented studio.

Nicholas ran the family’s Faberge jewelry shop, establishing himself as an artist and one of London’s first fashion photographers during the Belle Époque period of conspicuous luxury and lavish consumption. He sailed to Bangkok to personally deliver jewelry and objects of fantasy to the Czar’s friend and ally, the King of Siam.

As the story goes, in 1906 Nicholas was dispatched to London from St Petersburg to run the House of Faberge at 48 Dover Street to cater to the carriage trade. The shop later moved to tony 173 Bond Street in 1910 and closed in 1915 during the Great War. A far worse disaster followed the Faberge family during the Russian Revolution.

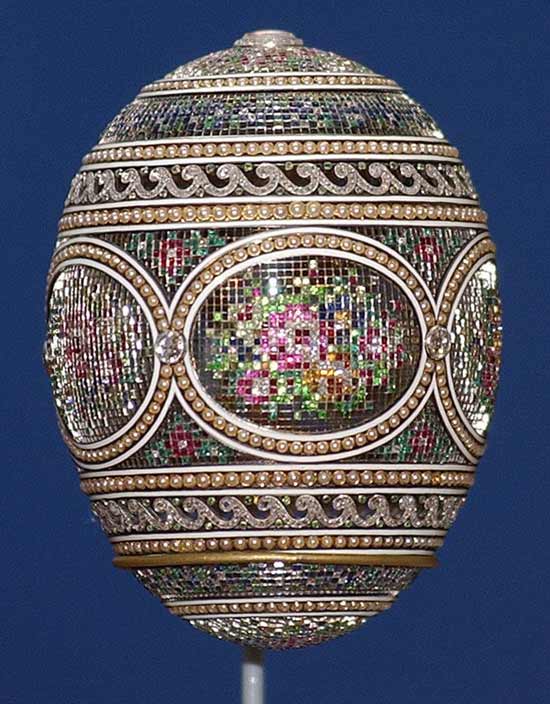

The House of Faberge was already internationally renowned as Peter Carl was commissioned by Russia’s Czar Alexander III in 1885 to create the first bejeweled Easter egg for his beloved Empress Maria Fedorovna. Peter Carl exceeded all expectations by creating the unique golden gift with a ‘surprise’ inside of a perfect ruby egg. It was customary in Orthodox Russia to celebrate Eastertide with eggs, a symbol of life, and a golden gem-studded one for the Empress was a most spectacular token of love. The gifting of Faberge eggs to royal wives and mothers became a Royal Family tradition.

Of the 56 Imperial Easter eggs created for the Royal Family, 45 of the rare pieces survive, and bring millions of dollars at auction. The Rothschild Faberge Timepiece Egg was auctioned at Christie’s London in 2007 for nearly 9 million pounds, over $14 million, and the jewel-encrusted Winter Egg was bought for $9.6 million in 2002 by the State of Qatar. Malcolm Forbes amassed the largest collection of 9 Faberge Eggs, later sold to Russian energy magnate, Viktor Vekselberg for over $100 million.

The House of Faberge at one time employed 500 to 700 goldsmith craftsmen who made over 100,000 jeweled and precious metal objets d’art. Czar Nicholas II, last ruler of the Romanov Dynasty, commissioned the House of Faberge to create original eggs each year for his mother, the Empress Dowager and his wife, Empress Alexandra.

When Imperial Russia was brought to its knees by the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution, the House of Faberge was seized and nationalized. Nicholas Faberge decided to remain in London. In 1918 the Bolsheviks stormed palaces, mansions and businesses, and the House of Faberge. Guards confiscated the priceless inventory and equipment, hauling it to the Kremlin. The Faberge family escaped Russia to Germany, eventually settling in Switzerland.

Germany, eventually settling in Switzerland.

The royal Romanov family was not as fortunate; Czar Nicholas, Empress Alexandra and their children were brutally murdered in a cellar in 1918. It is purported the execution order to shoot the entire family came from Lenin himself. Russia lost its Imperial glory yielding to socialist mayhem, massacre and destruction.

FABERGE LEGACY

Peter Carl Faberge was born in Russia in 1846 of Huguenot heritage. The original surname Favri changed in 1825 to Faberge after the family fled religious prosecution in the 17th century. The family lived in Bouteille, France and made their way east, settling in St Petersburg. Peter Carl trained as a goldsmith in St Petersburg, Dresden and Paris where he also gained business acumen. The Romanovs admired the House of Faberge creations of unparalleled excellence, and commissioned the atelier as jewelers to the Imperial Court.

After the Russian Revolution, the House of Faberge in St Petersburg was no more, later established in Paris. The fabled Faberge name had become a commodity unto itself. In 1939 the Faberge brand name was sold, and resold in 1964 to Rayette Inc. a cosmetics firm who marketed hairspray and men’s Faberge BRUT. The rights to the Faberge name changed many times during the 20th century, and in 1951 the family lost all rights to market anything under their own name. The post-Gilded Age period is referred as the “Wilderness Years”.

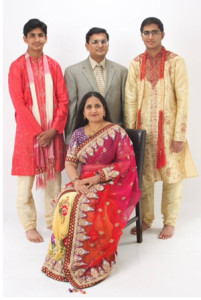

Among the Faberge name-owners were Unilever (cleaning agents, Lipton, VO5) who bought the rights in 1989 for $1.55 billion, and then it sold to “ELIDA Faberge”. In 2007, Faberge came under new ownership and the family name was restored to Peter Carl’s two great-granddaughters, Tatiana Faberge and Sarah (Woodall) Faberge. In 2009 the Faberge brand was re-launched with the legal use of their legacy; the fabled Faberge name.

The Faberge line of luxurious jewelry, objects of fantasy, accoutrements, and timepieces of timeless perfection are featured at Harrods London, and many Faberge-owned stores including Dubai, Qatar, Geneva, Paris and New York.

THE ST PETERSBURG COLLECTION

When Theo Faberge discovered his auspicious heritage, initially he chose not to emulate his famous grandfather, but instead, along with his daughter Sarah, created unique objets d’art, jewelry and objects of fantasy. In 1986 they created a line of egg-shaped objets d’art with precious metals, jewels and crystal, launching a limited edition of signature designs as The St Petersburg Collection by Theo Faberge. The Faberge father-daughter team created fifty egg designs, each limited to issues of only 750.

The exquisite music box eggs today are collected worldwide, and when they come available, can bring prices as high as $10,000 for the enchanting creations. Sarah Faberge designs exquisite eggs in the family tradition of excellence in limited editions, many for charity fundraising causes.

The world of mild-mannered Theo Faberge took on newfound fame when his own masterful exotic wood creations drew international acclaim and awards for excellence. Later the White House commissioned him to create an egg to celebrate its 200th Anniversary. All his life he had followed unwittingly in the artistic footsteps of his fabled grandfather, before even aware of his legendary heritage.

Theo Faberge died in 2007. His heritage endures as craftsman of superlative talent for his beautifully designed masterpieces. The legacy of the objets d’ art creators, bearer of inherent Faberge heritage, continues with Sarah Faberge at the design helm guiding the rebranding of the storied firm—the House of Faberge—jewelers to Imperial Russia.

The House of Faberge today is a high-profile giant in luxury goods retailing with a superb global marketing strategy for rebranding the storied name. Sarah Faberge forges ahead with her own innovative designs, modern and classy, and speaks of a fresh approach to the tastes of contemporary consumers. “We must move on,” she says.

Birth of a new World

The late 15th and early 16th centuries marked a period of revolutionary exploration as Man daringly took to the Seas in quest of knowledge and trade. The astounding discoveries of these journeys led to the publication of a new map of the world in 1507 which, for the first time in history, incorporated those four magic syllables that have become synonymous with the promise of Liberty and Justice: America. Not only was the newly named America defined as a continent to the West of Europe, the map also marked an all water route to the Far East. Thus was born a New World, driven by opportunity as well as commerce from these newly charted lands. Theo Fabergé celebrates the 500th anniversary of this momentous occasion with his Birth of a New World Egg.

The historic map, drafted by Martin Waldseemüller and published in Cosmographiae Introductio, is hand-engraved in lavish detail on the Egg’s 18-karat gold hand-spun shell. Laid out after the system of Ptolemy, the Greek astronomer of the first century A.D., each continent and island is reproduced by Theo Fabergé in painstaking loyalty to the 500-year old original, a copy of which was purchased by the United States Library of Congress for $12 million in 1999 after an almost 90-year quest to obtain the scroll.

Upon the Egg’s shell above and below the engraved map is a pattern of rope-work detail in white gold, framing two panels of symbolic clouds. The finial adorning the top of the shell is modeled after two heraldic cartographers’ dolphins, their faces styled in the manner of the major winds shown on the Waldseemüller Map.

The base of the Birth of a New World continues the Egg’s epic themes as, cast in bronze, two of the greatest explorers of all time whose fearless voyages contributed to the Waldseemüller Map are depicted in miniature: Amerigo Vespucci and Vasco da Gama. Dressed in the robes and Christian jewelry of their epoch, they stand heroically astride a symbolic log-book, its page indicated by a golden marker embellished with the signature Fabergé swags and set with a brilliant diamond. With one hand, the explorers hold the instruments and scrolls of their vocation while with the other they support aloft the golden Egg upon which is represented the Map.

Open the Egg to reveal the surprise: a model of da Gama’s majestic flagship the San Gabriel in sterling silver and 24-carat gold sailing upon a base engine-turned in mimicry of the ocean waves. Lift up the ship and see a final detail in the Fabergé family tradition: Theo has placed a perfect miniature of a 16th century mariner’s quadrant in silver and gold to guide the explorers of yesteryear, as well as today’s collectors, on their voyages.

Theo Fabergé’s Birth of a New World Egg is a wondrous tribute to America and its origins, and the apogee of craftsmanship and valuable design in the 21st century.

Limited to six for the World Market

Height: 13¼ inches