Contra Costa’s local air ambulance base has a community-service focused team that boasts top-flite medical professionals—and they’ve got your back.

Photos by Susan Wood

Inside CALSTAR 1’s air ambulance headquarters in Concord, a group of flight-suited staff members, including flight nurses, a pilot, and an administrator are relaxed and bantering. Some lounge on a couch watching TV news, others surf the Web, and one fixes lunch from Tupperware containers in the modest kitchen. But the calm, jovial mood changes instantly when a dispatcher’s call comes in from the CAL FIRE Emergency Command Center in Felton. Flight Nurse Michelle Starbuck sets aside her laptop, and yanks the top half of her black jumpsuit back up over her T-shirt as she moves quickly, gathering up helmet and utility vest. She and a second flight nurse immediately head out the back door to the tarmac at Buchanan Field Airport, where the compact CALSTAR MD 902 helicopter is waiting several yards from the building.

Pilot Robert Swarner leaves his salad and half-sliced apple on the counter in the kitchen, quickly checking a set of computer screens for location, weather conditions and flight restrictions. In a flash, he is out the door, belted into his seat, and starting the jet engines. The second flight nurse, Fred Maru, quickly circles the helicopter for a flight check as the blades began to whirl slowly above him. In less than five minutes, the gleaming black, white and teal blue CALSTAR 1 lifts off, heading to an automobile accident in Livermore.

“Felton, this is CALSTAR 1, departing for Livermore, waiting for further,” Swarner radios. The flight nurse in the front, just inches away in the small, glass-enclosed cockpit, writes the coordinates for the accident on a piece of white tape, and posts it on her right leg where he can see them. He enters the coordinates in the GPS system. An ETA is calculated, and obstacles en route are registered.

Soon, CALSTAR 1 contacts the local fire engine and its crew on the ground for an advisory. From 1,000 feet up, the entire crew’s focus is riveted on their approach to the scene. “You can sometimes view the story clearly from the air,” says veteran pilot Gary Garavatti, “you can see the damaged cars, often skid marks, and clusters of people and emergency vehicles. On every mission, we anticipate and plan as much as we can for the moment the flight nurses’ boots hit the ground. It may be on a state route, in a regional park, on a mountain, a dock, a beach, or a backyard—you name it, we’ve landed on it.”

Calculating the wind’s direction and the safest approach, the pilot sets down the aircraft several yards from the tangled automobiles, and the flight nurses are instantly meeting with onsite emergency personnel, crouching at the side of the injured man who needs air evacuation. This time, the injuries are not overly severe; immediate treatment includes securing an airway and stabilizing the spine.

Onsite firefighters help the nurses carefully load the patient onto a litter, strap him in, and bring him to the open helicopter bay. An IV is started, and pain medications administered. The helicopter, still running, becomes a mobile critical care unit, with onboard equipment including oxygen, monitors and a ventilator.

As the nurses work on the injured man, the chopper streaks through the air towards the trauma center at Eden Medical Center in Castro Valley. The pilot radios ahead to the hospital, and after a 12-minute flight, (half the time needed for ground transport) the MD 902 touches down on the helipad. Already waiting is a crew from the hospital. The air ambulance and hospital teams orchestrate a fast transfer of the patient onto a wheeled gurney, and move him into the trauma center, where doctors and nurses are already prepared for the case. CALSTAR’s flight nurses remain to debrief the trauma team, and when the patient is fully in their care, the transport crew loads up again, and heads home to the base in Concord, another 12 minutes away.

Like on most other calls, the main concept in the minds of the pilot and nurses is the safe transport of the patient within what’s known as the “golden hour,” or the crucial 60 minutes following a serious injury, when lifesaving measures have the greatest chance of successfully overcoming a trauma’s effects on the body.

“What we do is bring critical care directly to those who need it, and then provide expedited transport to the hospital,” says Swarner. “What I have to offer the patient is movement, in the fastest, safest way possible.”

About CALSTAR

CALSTAR, or California Shock Trauma Air Rescue, was envisioned in 1983 as an independent, regional air ambulance service that is patient centered and community based. It is a nonprofit public benefit corporation. In its first year, the organization flew about 250 patients to area hospitals. Now, it moves at least 300 per month, according to Ross Fay, CALSTAR’s director of the San Francisco Bay Region.

Those not involved in emergency response or transportation may never have heard of CALSTAR, but the people who work there live near you in Walnut Creek, Concord, Danville, San Ramon and other East Bay towns. They could well be the most interesting people that you’d never want to meet under the wrong circumstances.

CALSTAR 1 in Concord is one of 11 bases within the organization, which covers territory from Ukiah to Santa Barbara and from the Bay Area to the western edge of Nevada. The bases are manned 24/7 to respond to traumas including heart attacks, traffic collisions, gunshot wounds, recreational accidents, falls, burns and a wide variety of other situations. The service is also called upon to transport patients, including tiny neonates, between medical facilities. In 2009, the Concord staff of 20 completed more than 375 missions, in an area of roughly 50 nautical miles from Solano to the coastline to Southern Alameda.

CALSTAR’s aircrafts are modified with special medical interiors, high intensity searchlights and a tremendous range of radio frequencies for communication with any agency or location. The MD 902 Explorer, one of the newest helicopters in the CALSTAR fleet, is a twin jet-turbine aircraft specially designed without a tail rotor, and engineered for close maneuvering, minimal sound and rotor downwash.

Director Fay, himself a former Medevac helicopter pilot in Viet Nam and a former hospital administrator, says that “without question, the most spectacular thing about CALSTAR is the people who work here. They are so highly skilled, and dedicated; they eagerly respond to the call in sometimes extremely challenging circumstances, and they are completely patient-focused.”

“Most people are surprised that we are an independent agency, not a government service nor attached to a hospital. We exist as a stand-alone, a non-profit, which is unique, and we work from a completely different philosophical basis. Decision-making, day to day, is for the benefit of the patients we serve. “

CALSTAR sports an impressive safety record, last year celebrating 25 years of accident-free flying. The Emergency Medical Service (EMS) Director for Contra Costa County, Art Lathrop, recently praised CALSTAR as “absolutely vital in making sure that seriously injured patients are transported from their locations to the trauma center. Without them, we would be looking at transport times exceeding the ‘golden hour.’ The presence of that air medical service makes all the difference in situations where time to the trauma center is most critical.”

Joseph Barger, M.D., EMS Medical Director, added that “it definitely feels good to have a provider with a fantastic safety record. The hospital can’t be everywhere at the same time, but the air crews provide a high level of care outside the hospital that can make the important difference in improvements in outcome.”

Like other air medical providers, CALSTAR has critics who question the appropriateness of their charges, which can reach as high as $30,000, depending on the distances flown and treatment rendered. Fay counters that “a lot of people don’t realize that overall, actual revenue received is less than 50 percent of billed charges – ultimately, reimbursement and cash flow are critical issues for a nonprofit air ambulance – just like other medical organizations. We offer a membership plan and other programs that either eliminate charges altogether, or offer payment alternatives.” Fay estimates that less than a quarter of the 1,500 air medical helicopters in the country are run on a non-profit management model.

The Regional Trauma Center at John Muir Medical Center in Walnut Creek is CS-1’s primary destination, though CALSTAR also delivers patients to Eden Medical Center in Castro Valley, Queen of the Valley Medical Center in Napa, UC Davis Medical Center in Sacramento, and the pediatric trauma unit at Children’s Hospital Oakland. Other hospitals with helipads that accept and send out patients include Doctor’s Medical Center in San Pablo, Valley Care Medical Center in Pleasanton, Northbay Medical Center in Fairfield, and Vaca Valley Hospital in Vacaville.

CALSTAR helicopters were among the first responders to the collapsed Cypress Structure in Oakland after the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake. After participating in a recent “Every 15 Minutes” teen intervention program at a local high school, which dramatically depicts the consequences of drinking and driving, CALSTAR pilot Tim Tatman was approached by a student who thanked him for saving her father, who had been trapped in the Cypress Structure. The veteran pilot, since retired, was startled, and the impact of the conversation was profound – he realized that he had only flown one patient that day…and all these years later, here stood a young woman who had been an infant when that fortunate patient — her father — was rescued.

New Developments

Developments in the air medical transport industry that CALSTAR has adopted include refitting aircraft for transporting tiny infants—neonates—in ‘isolettes,’ large, specialized environments that provide them the best medical support. Formerly, this 400-lb. plus equipment did not fit in the cabins of most helicopters, but the MD 902 Explorer can accommodate it. This special type of transportation also requires a sophisticated, trained team to operate the equipment. The new MD 902 also has the smoothest ride due to minimum vibration, an advantage for these delicate patients.

CALSTAR helicopters, like some regional ground ambulances, also are equipped with portable 12-lead EKG devices in the field, which can provide early detection of heart attacks, benefiting patients whose vital information can be communicated to the hospital before they even arrive.

Working at CALSTAR

One of the striking things about the CALSTAR team is the teamwork, comfort and trust between personnel. “Everyone knows their roles well, and everyone supports one another. The missions develop a closeness—a family feeling. You get to depend on your teammates as your right hand, or an extension of your own eyes and judgment,” says Fay.

“Another thing that makes us different is the advanced skill sets of our flight nurses,” he adds. CALSTAR sends two trauma nurses on each mission, which is unusual among air ambulance organizations. The bar is also set high for pilots, who are required to have more than 3000 hours of specialized flight time to be hired, also unusual for the industry.

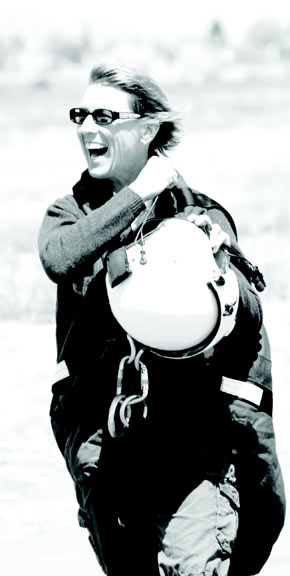

To provide a window into a day in the life of this air rescue team, journalist Laura Kaufman and photographer Susan Wood spent time with several staff members at CALSTAR’s base in Concord. Meet the people who make up the CALSTAR staff:

Michelle Starbuck, Flight Nurse

Michelle Starbuck, Flight Nurse

The Rescued Becomes the Rescuer

Michelle started her nursing career in a hospital ICU. But she found that she was showing signs of “burnout” after seven years in a cardiopulmonary unit, “where a piece of my heart would die right along with some of my patients.” She moved to the ER, where she encountered flight nurses from time to time, but never dreamed of becoming one. Then, in 1993, she spent a day in Napa, at Lake Berryessa, with a friend. On the way back to the car, she slipped off a steep embankment, tumbling 100 feet downhill – and was stopped by a tree trunk. She dislocated her shoulder and passed out every time she moved. A high-angle rescue soon took place, and a helicopter whisked her away to the hospital. “That’s when I thought hmm, this might be a great career,” she says. Two years later, she was hired by CALSTAR, where she has been almost 15 years.

Michelle’s family has an affinity for aviation. Her father was a private pilot, as well as her youngest brother. For many years, her dad kept his plane at Buchanan Field in Concord, where she is now based with CALSTAR.

In her years of flying, one case that remains particularly poignant for Michelle is the rescue of a Marin firefighter, Ruben Martin, who was pinned between two fire trucks in a 2008 accident that nearly cost him his life. He sustained a crushed pelvis and a gash along the full length of his left leg, which caused massive bleeding. Ruben remembers balancing on one leg, and beginning to diagnose himself, with grave doubts about his survival. Michelle was the Primary Flight Nurse responding to the scene. “Taking care of ‘one of our own’ first responders is always emotionally charged,” she says, “I was very impressed by what I saw at the scene, and especially at how Ruben, while he was still able, was trying to run the call.” She saw him reach down to try to test his own radial pulse. “He wanted to be flown to the hospital closest to his home, so he could say goodbye to his wife. But I told him no, we’re going to John Muir Medical Center,” recalls Michelle. “I knew his best chance for survival was at the trauma center closest to the scene and where they had the full range of emergency services he needed, including vascular surgeons.”

This split-second decision, as well as speed of transport, was critical in saving Ruben’s life.

Almost two years and more than eight surgeries later, Ruben used his determination and courage to recover, and is walking well and back in uniform, working part time, against amazing odds. Ruben tells Michelle, “I truly believe if it wasn’t for you, I probably wouldn’t be here today.”

Due to Michelle’s understated manner, one might not grasp her depth of skill, tenacity and ability to take control of a complex traumatic situation. But her co-workers all have “Michelle stories.” Pilot Gary Garavatti remembers a call in which Michelle stood on the door of a car that had rolled on its side, working with firefighters while they were using the Jaws of Life to extricate an injured driver. “We had to get inside the car to intubate him, while they were still trying to peel off the roof,” she explains. “I didn’t want to interfere with their work, but I had to get in there and get what was necessary done. “

Outside work, the 47-year-old Oakland resident is a marathon runner and enjoys Corvettes, camping, snow and water skiing and training her German Shepherd, Zora.

Simeon Mason, Pilot

Simeon Mason, Pilot

An Ex-Texan Alights in Contra Costa

Not long ago, Sim Mason ran an airport outside Tikrit during his active duty in the last Desert Storm rotation in 2005-06. He served 20 years in active duty as well as in the National Guard. His father was a small town doctor, and got his start as an ambulance driver in the 1950s. Mason sees his current job as an extension of that. Mason, his wife and daughter have lived in San Ramon for several years, and he loves the community that he frequently sees from the air. He appreciates that the pilots’ shifts allow them to be home with their families most days, more than most flying jobs.

In his role at CALSTAR, Mason finds he uses a lot of what he learned in the military. “There, we always trained for what we hoped we never had to do,” he says. “As an EMS pilot, you actually perform in these emergency situations constantly.” Like the other CALSTAR pilots, he is fixated on safety. “There are vital decisions constantly. For instance, on days like today, cloudy, with wind, anything could affect the flights. Can we launch? It’s a judgment call. Weather can deteriorate even during a flight. We have a slogan: Three to go, one to say no. That means that even if three team members are OK to fly, but one sees something detrimental, they can say no, and we will abort. The bottom line is always safety for the patient and the crew. “

In the event that the helicopter cannot launch, injured parties may be transported by ground, or by a CALSTAR helicopter from another base where conditions are clear, or by another carrier.

Mason, 48, is the sort of solid, salt-of-the-earth type, who inspires confidence in emergency situations. He says he is most proud of his flight nurse colleagues. “We just drive the ambulance, but what the nurses do is amazing. They provide a high level of care, more than in any other nursing field. They run a mini-ER in the back and have authority to perform higher level procedures, such as intubation and providing controlled medications, due to special certifications and continuing education.” Like the nurses, pilots receive constant training at CALSTAR and are evaluated every year.

One recent advance in safety equipment that Mason and the other pilots are enthusiastic about is the night-vision goggles used to enhance visibility in the dark. “The difference is amazing,” he says. “It’s the latest technology available. It can allow us more safety in missions that might have been turned down before due to impossible visibility.”

“I’ve always been a Type A adrenaline junkie, so this job fits me nicely. I’m also a people person, which is very important. Though we put up with hours of boredom surrounded by moments of action, there is plenty to do in the off-time; from shopping online to washing the aircraft, to studying medical or aviation books for the classes we have. There is no nervousness or tension—people relax.”

Some of the toughest flights are the ones involving kids. “You see a complete demeanor change in the crew,” he says. He estimates that 90 percent of calls to his hometown are related to kids. “We get a lot of horseback riding injuries, and other recreation accidents,” he says. CALSTAR is a great help on nearby Mt. Diablo, where the crew sees biking injuries from blown tires, i.e., broken collarbones. “We can provide great relief to these athletes,” he says. “It’s an hour to get out of there by ambulance, but three minutes to John Muir by helicopter. That’s an hour less of pain. The most preventable accidents I observe daily are those with a lack of helmets with the chin straps fastened – without that, the helmet can fly off on impact,” he says. He also cautions Contra Costans about driving after the season’s first rain. “Six months worth of oil and other substances on the roads contributes to a lot of accidents,” he says.

Mason, like the others, likes his job. “This is very much a family. The crew has all helped make our trailer homier, with appliances, books and movies – but sometimes, we start a movie six times before we can finish it,” he laughs.

The Nuts and Bolts of Flying

This is the first civilian job for the diminutive mechanic, who grew up in the L.A. area and always knew she wanted to work with her hands. Her military recruiter aimed to place her where she was most qualified, and on the list of options was battalion construction, work with the Seabees, or aircraft mechanics. That’s where she landed. She got her on–the-job training with Seahawk H60s, the Navy version of the Blackhawk helicopter.

Billie Jean was the only woman in her “A” School basic aviation maintenance class in the Navy, but doesn’t feel she was treated differently. At CALSTAR, however, it’s a different environment completely. “It’s a family. I love what I do—keeping the equipment up and running and where the crew wants it. I have quite a bit of autonomy—a base mechanic profile is someone who can work very independently, but I actually have fun here,” she says.

One problem that brought out Mendoza’s sleuthing skills recently was an issue with an onboard radio. Pilots and crew complained about poor audio during a mission. “I’m the one to unravel the problem,” says Mendoza. She is quiet, but methodical, and uses both her gut and painstaking procedures to diagnose problems. (In this case, she says, it was the control head.)

Besides daily routine checks of the aircraft, Mendoza periodically helps take apart and inspect her helicopter—entirely. This and other heavy maintenance is mostly done at the CALSTAR headquarters in Sacramento, which includes a large hangar at McClellan Air Park equipped with the specialty tools designed for each aircraft. The mechanic is relied upon to troubleshoot and make critical decisions about the airworthiness of her aircraft. “You have to be kind of paranoid,” she says, “on my drive home, I run through everything I’ve done that day. Everything is double-checked and triple–checked to be mission-ready. I know a mechanic who even dreams about what he’s done at work.”

Off duty, the 26-year old enjoys hiking and just relaxing, or fixing up her new home in Vallejo. She has a reputation as the staff member who is constantly eating. She waves a chicken leg to illustrate a point: “I am really happy here; and I’m happy that I picked a place that can say it’s been accident-free for 25 years.”

Passing on the Inspiration

“I remember the exact minute I decided to be a flight nurse. It was in my first semester at college. I knew I wanted a healthcare field, but a local flight nurse spoke to one of my classes with so much passion and confidence, she inspired my decision,” says Barlow.

The Idaho Falls native first came to California as a travel nurse and fell in love with the Bay Area. Starting in Critical Care, Barlow enjoyed the autonomy and challenge of that specialty. She tried other units, and came full circle back to flight nursing. She chose CALSTAR “because the interview scared me—I saw how much opportunity to learn I would have, and what a jumping-off place it would be to really blow up my career.” The deciding factor was the positive environment and safety culture of the organization. “The big thing Ross (Fay) is concerned about is keeping us safe,” she adds, noting that people, including her parents, perceive her job as more dangerous than it is. “As a team, we really adopt that philosophy. Every time the phone rings we are all on our toes, everyone holds each other to that. We are vigilant about our safety. It’s important to treat every time like the first time.”

Barlow has two 24-hour shifts per week. The crew sleeps overnight in small rooms in the narrow portable building; their lockers hold a few essentials as well as an assortment of family pictures, cartoons, artifacts, and random items of décor. “Even when you’re not working, you’re not at home,” Mary says. “Some nights you get very little sleep. We’re paid to take care of people whenever needed. The priority is being mission-ready.”

“What I enjoy so much is being around very high-functioning, proactive, motivated co-workers. I’ve never been surrounded by so many intelligent people, with the ability to think outside the box. The knowledge of the pilots is amazing, from local geography to weather to everything else. And everybody here has a great sense of humor.” Another benefit of the job: “When you’re in a situation where somebody needs help, and you have the skill set to provide it, that’s a wonderful feeling. It could be the worst thing that has ever happened to them—and I love being able to contribute to making it better.”

After the tension of rescue work, she says, staff needs a cathartic release, and people need to remember not to take themselves too seriously. “Every call is different with so many unknowns and variables. You’re thrown a complete puzzle, and have to think on your feet. You have one chance to do it right. Everybody has a bad call now and then. You review it in your mind, and wonder if you did the best you could. Those days define you. We’re all hard on ourselves; that’s when our partners are most supportive. Reviewing a situation is where you find what the insight is for you.”

Barlow loves working with high school students, and recently went to George Washington High School in San Francisco to participate in a Career Day. “Especially for young women, role models are so important, showing them how to be physically strong, yet feminine,” she says. She herself loves to keep fit, and runs, camps and goes rock climbing.

Any advice for Contra Costans who want to avoid incidents that bring CALSTAR to their doorstep? “Please, please, wear a helmet! Parents, please put helmets on your kids when they bike or skateboard. Some of the saddest things I’ve seen are kids who sustain head injuries that could have been prevented. Mitigate those risks as much as intelligently possible. You have a huge opportunity to drastically change your future, or your child’s future.”

Her last words, with a smile: “I would love to be with CALSTAR until I retire.”

You Don’t Know Us Until You Need Us

According to Garavatti, people just don’t understand the value of a highly-skilled air transport team until they’ve been a victim. After 27 years in law enforcement, including terms as a motorcycle cop, helicopter pilot and traffic reconstruction investigator, plus stints flying for KGO and Channel 4, he has seen it all. “The absolute most important thing in a traumatic injury is time,” he says. There is no other way besides the helicopter to go right to where someone’s hurt, avoid traffic, and get directly to the hospital.”

He notes that polished interpersonal skills are hugely valuable in the environment of teamwork, a close-quartered airborne situation, and in coordinating patient care with safety and speed.

Helicopter pilots at CALSTAR must have a minimum of 3000 hours of flight time – a very high number, even for former military pilots, Garavatti says. Experience matters, in ways people might not expect.

He outlines a common scenario during a call:

“At the scene, the pilot gets the estimated weight of the patient, and quickly puts together formulas for balancing the aircraft, calculating in the weight of fuel and the known weight of the nurses. We usually know what hospital we’ll go to, based on distance, and patient condition, and can punch in coordinates to the GPS navigation system. When the patient is stabilized, the nurses call in a patient assessment to the receiving facility, i.e., ‘this is CS1 with a trauma activation, male subject, victim of gunshot wound (GSW), alert and oriented,’ followed by time enroute to the landing helipad at the hospital so the trauma team is readied for what is arriving in a matter of minutes.”

“I’m in awe to know what the nurses are doing in the back,” he adds. He tells them one minute away from landing to get back in their seatbelts, and they give a thumbs-up and help clear the helicopter during landing. Garavatti gloves up and helps unload; he often helps carry medical equipment into the hospital with the patient. As soon as the team returns to the Concord facility, the nurses restock medical supplies, and he refills oxygen tanks and fuel. Then, charting is done.

“In jobs like this, you’re going to see a lot of bad things, and it has an emotional impact over the years. I try to keep the emotional end out of it, otherwise it’s very affecting. Sometimes, events such as the recent attack on the Richmond girl at her school really stay with you. You have to keep focused.”

“Overall, I love this business. I have a real sense of purpose in this job. I look forward to coming in and putting on the flight suit. When you’re wheeling someone into the hospital, and they look at you, you know you’ve really helped them, and that’s what it’s all about.”

What does he wish other people knew to make his job easier? “I can tell you from my experience, the absolutely most dangerous thing is auto accidents, but people still take driving for granted and do it casually.” DUI collisions, drug use, texting and cell phone use while driving, and not wearing safety belts are some of his issues. Fall prevention—from windows for kids, and also for older adults, is also more important than people realize, he says. “Accidents really make people wake up to a lot,” he says. Take a tip from the experts before that happens.