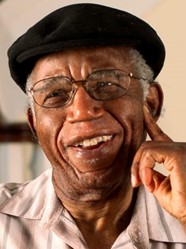

It was while teaching in Nigeria, that I first was exposed to the African Writer Series, novels published by Heineman. I was immediately captivated since they opened up a whole new world of literature to me. After reading Chinu Achebe’s ‘Things Fall Apart’ followed by ‘No Longer at Ease,’ I wanted more, I needed to be educated about this amazing country. Even with all of my advanced degrees my education was falling very short as a preparation for the work I was committed to. Achebe has been called the ‘Father of Nigerian Literature’, in which he frequently weaves together oral tradition with Ibo folk tales. Against a background of cultural norms, he intertwines changing societal values, and the individual’s struggle to find a place in this ‘new world.’ Achebe’s expression of anticolonial sentiments showed me how naïve my own English attitudes were and how simplistic my understanding of Nigerian history. All of this was a revelation to me, and I wanted to learn more. That in itself had its own challenges since I was working in a fairly remote part of the country where there were few amenities, and the nearest bookstore over two hundred miles away. But I was hooked!

It was Achebe’s works that turned me to another Ibo writer, Cyprien Ekwensi. His ‘People of the City’ was the first major novel to be published by a Nigerian. His most widely read novel, ‘Jagua Nana,’ appeared in 1961. It was a return to the same setting of People of the City, the capital Lagos, but boasted a much more cohesive plot centered on the character of Jagua, an aging prostitute with a love for the expensive. Her life personalized the conflict between the old traditional and modern urban Africa. Almost better known for his short stories, I was particularly taken with ‘Burning Grass’, a collection of vignettes about a nomadic Fulani family.

I read ‘House Boy’ in French by Leopold Oyono, a writer from the Cameroun, who later became ambassador to Libera. I followed this by ‘The Old Man and The Medal’, both books reflecting the growing sentiment of anticolonialism of the 1950’s. T.M Aluko, a Yoruba writer uses similar themes in his novel ‘One Man One Matchet.’

Wole Soyinka, also from the Yoruba tribe, and eventually winning the Nobel Prize in Literature, held me riveted with his focus on oppression of the poor and exploitation of the weak by the strong. Nobody is spared, neither the white speculator nor the black exploiter. During my ten years in Nigeria, he of all the writers made me question what I was really doing there.

I discovered several female writers which shouldn’t have surprised me but did, since at the time, there were few females in academia generating creative thought and expression. Flora Nwapa is considered to be the ‘Mother of Modern African Literature’ and the forerunner to a whole generation of African female writers. Balaraba Ramat Yakubu wrote books of love in Hausa, a language I was avidly learning. Oyindamole Affinnih gave up law to write and publish among others, two beautiful novels, ‘A Tailor-made Romance,’ and ‘Two Gone…Still Counting.’

The modern generation of Nigerian female writers has produced several remarkable women, but none more so than the Ibo writer, Chimamanda Ngozi Adiche. Her novels have garnered universal acclaim. The first two, ‘Purple Hibiscus’ (2003) and ‘Half of a Yellow Sun’ (2006), used the tension filled political situation of Nigeria as the backdrop. The latter set amidst the violence of the Biafran war, follows the lives of two sisters, and their lovers, clearly set Adichie apart as a talented new voice. Interestingly enough, Adichie herself was born seven years after the end of the civil war.

‘Americanah’ (2013) is a book every person concerned with racism, immigration and globalization should read. I feel it is more pertinent today than when it was first published. Essentially a love story, it traces the lives of Ifemelu and her childhood sweetheart Obinze, who are separated when she goes to study in America. She is fortunate to leave Nigeria during a time of military dictatorship, and that moment is captured by her Aunt Uju, who having emigrated a few years earlier, becomes her confident. Never slow to speak her mind with a bluntness and insightfulness that often shocks, but is always close to the truth, she tells Ifemelu, ‘the problem is that there are many qualified people who are not what they are supposed to be because they won’t lick ass, or they don’t know which ass to lick, or they don’t even know how to lick ass.’

Alternating between past and present, Ifemelu tries to adjust to her new home, learning what it really means to be black in America. The award-winning novel is a love story that straddles three continents, Africa, North America, and Europe. It’s about love, loneliness, and race. But it’s also a poignant, funny, sometimes scathing look at the reality of being a new immigrant in the USA…from an African perspective.