I don’t remember when I first became interested in the history of HMS Bounty and the mutiny by the crew that took place in 1788, or Pitcairn Island where the renegades settled. My childhood fascination was probably sparked by portrayals in rerun movies, and being an avid stamp collector, I yearned for Pitcairn stamps.

As a youth I was fascinated by the “Mutiny on the Bounty” story and we had learned in history class that the ship had actually docked near my own hometown, Cape Town, South Africa, before crossing the Indian Ocean to Tahiti.

Then, a few years ago, my friend, Wallene Nelsen, and I, visited Smithsonian Museum of Natural History where we were invited to the off-limits botany specimen storage room. The curator showed us actual plants collected on Captain Cook’s expedition in the 1770s by Sir Joseph Banks. Banks was the same botanist who referred the Bounty’s William Bligh to King George III, to bring breadfruit saplings from Tahiti to Jamaica. Imbued with curiosity, I requested to touch the leafy specimen before it was returned to the drawer.

Thus, the islands were vaguely on my radar with the Bounty having docked in my own hometown, yearning for Pitcairn stamps, and being so close to the actual breadfruit specimens collected by Joseph Banks.

As the story goes, after cruel punishments and floggings by Bligh, Master’s Mate Fletcher Christian commandeered the vessel and banished Bligh and his followers to an open boat, setting them adrift in the South Pacific Ocean. After many weeks at sea they finally reached land, returned to England and demanded the mutineers to be hanged.

Although the mutiny was romanticized in books, it was not until the story hit the big screen that Fletcher Christian became a maritime hero in three films; Clark Gable and Charles Laughton, Marlon Brando and Trevor Howard, and Mel Gibson and Anthony Hopkins, in blockbuster renditions of the nautical crime of the century.

The thrust of the HMS Bounty story was that Sir Joseph Banks referred Bligh to King George III to secure breadfruit plant saplings in Tahiti, then to deliver them to Jamaica to grow as cheap foods for slave workers. The trees yielded about 200 high protein fruits per season and also provided timber for outriggers and latex for boat caulking.

Successful transplants of seedlings to Jamaica meant bonuses for Bligh and success for botanist Banks. The ship’s great cabin was refitted to hold over 1000 plants—plants that required much of the ship’s limited drinking water.

While on the extended Tahiti layover, the crew nurtured the Jamaica-bound breadfruit saplings for ten months, as many of the sailors became enthralled by the tropical maidens. Bligh admonished the raucous sailors, and some were mercilessly flogged. When the Bounty departed Tahiti with breadfruit saplings, the crew rebelled.

Fletcher Christian had taken up with an island maiden and was not about to abandon her. With his anger roiling, Christian lead the mutiny against Bligh and banished him along with eighteen others, to a twenty-three-foot open boat, to fend for themselves in the vast ocean.

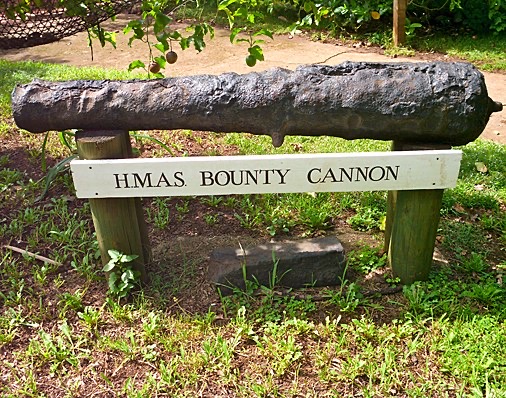

He commandeered the HMS Bounty with eight roguish sailors and returned to Tahiti to pick up six local men, eleven women, and one infant. The hijacked Bounty zigzagged the South Pacific for nine months in search of safe harbor far from Britain’s reach. In January 1789, they landed at an inlet on the volcanic outcrop island of Pitcairn in a four-island archipelago. Christian named the inlet “Bounty Bay,” and settled his ragtag colonists near abundant food sources. They stripped the Bounty of lumber, canvas sails, and supplies, scuttled it, and set it afire to prevent escape.

I would imagine they redeemed the breadfruit samplings to grow for food and used all possible survival devices as they colonized their lost paradise, invisible to the outside world.

But trouble was brewing in the utopian paradise as British sailors, and the Tahitian men, fought among themselves, often over women, and many died in the first two years, including Fletcher Christian.

John Adams was the sole mutineer survivor as shortly after their arrival, all the others died. Some were murdered, one committed suicide and others died from various causes. In any case, their names remain etched in history; Fletcher Christian, Matthew Quintal, William McCoy, William Brown, Isaac Martin, John Mills, John Williams, and Ned Young, whose descendent, Kevin Young, has added to this story.

Despite despair, isolation, and fear of capture, survivor John Adams, the Tahitians, and subsequently future descendants of seven generations have lived on Pitcairn and Norfolk Islands for 230 years to the present. The multi-generational descendants, living links to the storied Bounty, are still preserving their Anglo-Tahitian culture.

Isolated Pitcairn Island, an Overseas British Territory, has the smallest population of any democracy in the world. It lies within the Henderson, Ducie and Oeno archipelago. Pitcairn, the only inhabited island, is 3,500 miles equidistant from New Zealand to the west and Peru to the east, has a combined area of 1.6 square miles, and the highest point is 1100 feet. It has internet access and one television channel. Adamstown is the capital.

In the 1930s, the population swelled to 233, however, today only about 50 people live on Pitcairn. No planes can land, no big ships can dock. Water and fuel are scarce, and to preserve energy, electricity is turned off between 10 pm and 6 am. Island transportation is by foot or quad ATVs, and passengers, supplies, and mail arrive from New Zealand once every three months on the island ship, Silver Supporter.

Accommodation and meals for visitors can be arranged at local homes with advance reservations. Most families have vegetable gardens and fruit trees. Breadfruit is harvested by “shooting down” as they are too high to reach. There is one school, a church, medical center, general store, and post office that still sells collectible stamps and first day covers.

When cruise ships visit, they drop anchor in deep waters, and weather permitting, passengers are ferried into Adamstown by longboats or ship tenders, where locals eagerly sell handmade wares, wood carvings, jewelry, tapa cloth, island honey, and handmade soaps. Pitcairn Island is actively seeking immigration and offers free land to those who qualify.

So, with my triad of links to HMS Bounty that moored near my birthplace two centuries before, avid Pitcairn stamp collecting, and a serendipitous Smithsonian connection with botanist Banks’ specimens, I decided to contact some Pitcairn inhabitants for my story.

Heather Menzies Young kindly put me in touch with Pitcairn’s deputy mayor, Kevin Young, a direct descendant of original Bounty colonist Ned Young, who emailed me his own words for my ALIVE article:

Life on Pitcairn can be busy. Our aging community is very small, so keeping the island maintained and functioning at a reasonable level requires all but the very young and elderly to participate in some way. Combine this with a self-reliant lifestyle, and time becomes a much-valued commodity.

In the summer months, a number of cruise ships break their journey between French Polynesia and South America with a call at Pitcairn. If the passengers come ashore, our population can swell to a few hundred for the day. Other ships invite us to set up a market on board so passengers can buy local crafts and wares. A popular choice is to write letters and postcards which are brought ashore and mailed from the Pitcairn Post Office. With some ships carrying several thousand passengers and crew, it can stretch us to capacity for those hours but the interaction with passengers and supplementary income is always welcomed.

Passengers often ask how we live on this small remote island. When they learn our homes are similar to theirs with electricity, satellite broadband, and appliances there’s often surprise. What’s less familiar to them is drinking rainwater from unpolluted skies, fish caught from pristine waters, and vegetables fresh from the garden for the evening meal.

If they were to ask me why I live on Pitcairn, I would tell them I was born here, a direct descendant of the Bounty settlers. My family has lived here for 230 years. Some set great store by the connection to the Bounty but I live here because I chose the Pitcairn lifestyle in retirement over the equivalent, time demanding, urban life in New Zealand I returned from. Pitcairn’s rugged beauty and sub tropical climate is a bonus!—Kevin Young