The long-awaited book Images of America: Italian Oakland, by now-retired award-winning Oakland Tribune reporter and columnist Rick Malaspina, portrays East Bay Italians through some 200 vintage photographs, interviews and commentary. Rick emailed me that his book, with the assistance of actual family remembrances and photographs, was his parting gift to the Italian community before relocating to South Carolina.

I researched the history of the East Bay Italian community, asked a lot of questions and interviewed some Colombo Club members who enlightened me how their social club fits into the cultural paradigm of Oakland, specifically those who hailed from Italy’s north-western region.

Immigrant Italians, mostly from Piedmonte and Liguria, who had settled in San Francisco’s Little Italy in the 19th century, became dislocated when the 1906 earthquake toppled The City from its foundations and entire neighborhoods were consumed by fires. They picked up their possessions and relocated across the bay to Oakland where they found ample masonry work and jobs in the rock quarries to rebuild not only San Francisco’s infrastructure, but also to gravel and macadamize miles of newly needed paved roads for the new horseless carriages—the automobile.

The rock and gravel quarries in the coastal range yielded greenish-grey sandstone and a near-basalt quartz diorite, used as aggregate which was shattered manually in mountain pits by 30 to 50 men at any given quarry during dig season. One of Oakland’s largest quarries once occupied the area where Rockridge Safeway and Shopping Centre now stands. Since the 1890s, Piedmont Hills quarries yielded about 20,000 cubic yards of aggregate a season, all shattered to pebbles by the powerful arms of about 35 men in the pit caves busting bedrock, pounding hand-forged iron plug drills, flat-wedge plugs and cape chisels weighing as much as four-and-a-half pounds apiece. There were occupational side effects unbeknownst at the time; men who literally moved mountains working the quarries were prone to lung ailments from inhaling lime dust, asbestos and other pulverized stone particles.

At those rock quarries the Piedmontese labored for meager wages; most being unmarried men who worked to save enough scudi to return to Italy, others toiled for fare money to bring their families to America—digging out the mountain, slogging in the quarry cave, nella cava—six days a week for less than $2.00 a day. After a week of hard work their Saturday nights were lonely—living in cheap overcrowded quarry-owned boarding houses they yearned for their families and talked of the Old Country. Maggiorino Lovisone, who lived across the street from the Bilge Quarry, offered the use of his basement for Piedmontese paesani to play cards, enjoy wine, traditional foods and commiserate in their native language and… voila, a social club was born! The quarry club fellowship initially had meetings in the basement which evolved to become the Oakland Colombo Club, founded in 1920 by 34 immigrant pioneers—among them Maggiorino Lovisone and Pietro Puppione.

When I asked the club’s past president, Rich Puppione, about his fondest memory he offered, “I was honored to have the opportunity to reside over the club’s 90th Anniversary Celebration—my grandfather Pietro was a charter member in 1920 and I pictured him and my grandmother Lucia with their amici celebrating the grand opening of the Colombo Club…”

Chuck Reyna kindly introduced me to his in-laws and I met with Elma Roggero Dickson and her husband Don; she told me her father was the club’s chef. “My father Marco Roggero was a charter member when he was chef at the Claremont Country Club—then he became the first main chef at the Colombo Club.” A vintage photo shows Marco Roggero happily preparing the meal for boxing legend Rocky Marciano’s visit in 1959.

Then John Penna told me about the day he met the undefeated heavy weight champ. “When I picked up Rocky Marciano at the airport I got a flat tire. Rocky sat there and watched me change the tire with his arms folded.” Penna laughed as he shared vintage photos of Rocky at the club.

The Colombo Club with a 950-men membership, plus the active women’s auxiliary, is presently the largest Italian social club in the United States whose enduring mission is to preserve Italian culture and Piedmontese traditions. The Piedmonte region, translated ‘foot of the mountain’, borders France to the west and Switzerland to the north. The capital, Torino, named Augusta Taurinorum during the Roman Empire, now thrives with manufacturing industries and is home to the Agnelli empire Fiat factories. Iverea is home to Olivetti, Alta produces Ferrerro chocolates and Monferrato is Italy’s premier wine district.

It was in 1920 when the founders bought a parcel of Oakland property at Broadway and 49th Street, within a sledgehammer’s throw of the quarry, and formed the Colombo Club. When membership expanded, they built their present building on Claremont Avenue in 1951. The club, presently under the presidency of Tony Tedeschi, not only promotes Italian-American culture, but also raises funds with the women’s auxiliary, for college scholarships for members’ children or grandchildren. The spacious banquet facility seats 565 diners and traditional Italian cuisine is prepared for weddings, social events, fund raising projects, family dinners and meetings.

A women’s auxiliary young member, Maria Falaschi 32, literally spent her childhood in the Colombo Club. “While in New York earning my MBA in Internet Marketing, I often reflected on growing up in the club and the invaluable influence so many successful individuals had on me, both in business and the Italian community…”

In addition to the club’s many social activities, Carlo Tamburrino, Laura Ruberto and Maria Grazia offer Bambini Ciao classes for children age two to eight on the first Saturday of each month where they play games, sing, do art projects and learn Italian. Carlo encourages parents and children to speak only Italian during the sessions thus promoting culture and keeping the Italian spirit alive.

The Isabella Room is the heart of the club’s historic archives, compiled by past president historian John Penna, highlighting the past with photographs of well-known visitors or images of ordinary people in daily lives capturing a certain nostalgia of Little Italy in the Temescal neighborhood. The New Americans proudly embraced their adopted country albeit still imbued with the spirit of their Italian homeland—the heritage that endures today.

“I organized the club’s history in the Isabella Room as a token of heartfelt appreciation and to recognize those who immigrated to America to provide better lives for their families…” Penna said proudly.

The Colombo Club — Home Away from Home

The Colombo Club, a longtime hub for the mutual benefit of the Italian-American community, boasts a host of renowned visitors; athletes, civic leaders and politicians alike. Oakland was home to the Oaks, a baseball club managed by Casey Stengel who in 1948 took the team to the Pacific Coast League Championship. Many players, sons of Italian immigrants, stopped at the club to socialize and enjoy traditional Italian wine and food, fellowship and camaraderie. Among the athletes were Billy Martin, Ernie Lombardi of the Cincinnati Reds, Harry “Cookie” Lavagetto, Brooklyn Dodger’s third baseman, Dario Lodigiani of the Philadelphia Athletics and Martinez-born Joe DiMaggio, who signed with the New York Yankees in 1936, and was a one-time celebrity bartender at the club, rumored to shake up the best Martinis.

Boxing Hall of Famer, Rocky Marciano, was a guest in 1959. He retired in 1956 as the undefeated, Heavy Weight Champion of the World. He has a place of honor in the Isabella Room’s photo gallery that tells the club’s visual history, the essence of the past—rekindled by images of those who passed through the storied doors—the Italoamericani who impacted the culture and heritage of Italian communities.

On my first visit to the Colombo Club, I was warmly welcomed by Ray and Pat Frantangelo. An instant home-away-from-home ambiance was twinned with genuine warmth. I was a guest of Tom Gallinatti, retired Battalion Chief of Oakland Fire Department and Fire Fighter Engineer Jennifer Schmidt, board members of the non-profit Police and Fire: The Fallen Heroes. After introductions, I was promptly spirited to the heart of the club—the bustling kitchen—where chefs were cooking for 500 diners on family night in the spacious banquet room and then I was given a tour of the storied Isabella Room. Yes, the Colombo Club truly lives up to its reputation as being a place of familial camaraderie and a home away from home.

The Great Italian Diaspora

Those who immigrated in the 19th and 20th centuries were not the first waves of intrepid Italians, besides of course, the Genovese, Christopher Columbus. Giovanni da Verrazzano was the first European to enter New York Bay in 1524. The first permanent resident was Pietro Cesare Alberti and the Venetian Tagliaferro family was the first to settle in Virginia. In the 16th century, Antonio Pigafetta from Vicenza circumnavigated the world with Magellan. Filippo Mazzei was Thomas Jefferson’s friend whose maxim was ‘all men are by nature free and independent’ and we all know that Amerigo Vespucci gave his name to the Americas five hundred years ago.

In 1823, an explorer Giacomo Beltrami from Ferrara discovered the mountain headwaters source of the Mississippi, in a location later to become Minnesota. Italian Jesuits and Franciscans founded the universities of San Francisco, Santa Clara and Gonzaga and the six Piccirilli brothers carved the Lincoln Memorial sculpture and Italians painted the Capitol murals. Italians served in the Revolutionary and Civil Wars, fought in WWI and one million Italian-Americans served in WWII.

What were the catalysts to spark such massive migratory waves from Italy to America you ask? The first transatlantic wave started after Garibaldi’s 1861 Unification of Italy. The country’s once powerful City States became rapidly integrated causing a breakdown of agrarian societies; the Mezzogiorno region of Southern Italy and Sicily saw soil erosion, deforestation, a lack of coal and iron for industry and tenant farmers and landowners’ crop productions diminished by the emerging fierce competition from the industrial north. Birth rates rose, death rates fell—overpopulation meant fewer jobs and between 1876 and 1924 4.5 million migratory ‘birds of passage’, so-called by historians, emigrated to South and North America with the intent to work abroad and return home.

Natural disasters also played an important role in driving migration; when Vesuvius erupted in 1906 and Etna in 1910, the homeless fled, but the catalytic thrust for the mass exodus was the 1908 Messina 7.2 earthquake and forty-foot tidal waves in the Straights of Messina that destroyed Sicilian and Calabrian coastlines, killing 100,000 and leaving hundreds of thousands homeless and jobless. The devastated survivors looked to the western horizon and most sojourners stayed forever.

My children’s great-grandparents were part of that Italian diaspora—as intrepid ‘birds of passage’ they migrated to America—the land of golden opportunity. Now a century later we celebrate the pioneering spirits of Rocco Venezia from Montescalioso who journeyed from Basilicata in 1909 and Giuseppe Brocato from Cefalu, Sicily who stowed away in 1911—both men on the same daring quest; to work and earn passage for their families who were to ultimately reach California and achieve better lives in America. If those valiant exiles who arrived on these shores, from all over the world, could have telescoped into the future and witness what their descendants have achieved—they would be gratified in the realization that their sacrifices were not in vain.

Those Italians, who often sadly left their homeland, braved the cramped steerage quarters, often with just a pocketful of lire, were the same ones who built the soaring skyscrapers, subways, roads and bridges—they built American cities with the sweat of hard labor and a fierce determination to succeed. Statistics show that ninety percent of public works projects involved Italian labor—and many moved west, to already-established enclaves where religion, traditional foods, ideals, and family values gelled with their own. As early as mid-1800s, a thriving Italian community had already settled in San Francisco and by 1869 The City was celebrating Columbus Day with parades and festivities.

In 1908, two years after the earthquake and fire, the San Francisco Italian community was able to secure their savings and apply for loans through the concept of branch banking when A.P. Giannini founded the Bank of Italy—later to become Bank of America—thus spring-boarding Italian-Americans into business ventures all over northern California.

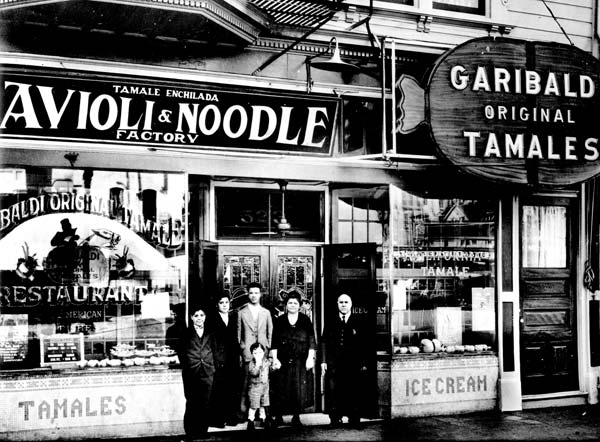

Many Italian-owned businesses later burgeoned to multi-million dollar industries. Such as the example of the resourceful Genovese folk from Genoa, who when they saw the need for trash pickup, bought wagons, horses and bins, then established neighborhood collection routes. To identify themselves as bona fide scavengers, the then-term for trash haulers, they painted their ‘honey-wagons’ blue and climbed the Oakland hills from sunup to sundown gathering refuse from backyards. There were ancillary recycling angles too, before such a word was invented; bottles were washed and sold to wineries, metal to scrapyards, rags to repair shops, newspapers to paper mills, and food scraps sold for compost or hog-feed at Italian-run pig farms. The refuse was sorted by hand, wearing no gloves or aprons, and the unusable surplus was dumped.

By 1920 the Genovese-Americans had organized co-operatives consolidating operations into one major Oakland Scavenger Company where men worked for a buck a day and two on Saturdays. In the 1980s, owing to labor disputes, many original share-holders sold to corporations thus disintegrating the long-held privately-owned enterprise. Now big blue trucks collect garbage, and high-tech efficient ‘honey-wagons’ are corporately camouflaged with new-fangled words; waste management, recyclers and ‘recologists’.

So how do we measure the cumulative impact of quintessential Italian historical culture on our own contemporary culture? We could look back in time two millennia when Julius Caesar and Mark Antony lead the expansionist Roman Empire, influencing twenty million people in the Mediterranean Rim. We could be awed by their still-standing lithic monuments in Italy, North Africa, Spain, England and Turkey. We could touch just the tip of the Italian cultural iceberg and identify centuries of influence; monumental sculptures or the enduring art of Da Vinci, Michelangelo, Botticelli and Caravaggio, the music of Rossini, Puccini, Vivaldi and the 20th century tenors Enrico Caruso, Franco Corelli and Luciano Pavarotti.

But wait, we must not be remiss in mentioning how Italians first impacted this great land when Columbus, a man from Genoa, financed by Queen Isabella, landed on San Salvador in 1492, followed by cartographer Amerigo Vespucci after whom the Americas are named. We may refer to the Renaissance Medici dynasty, the banking and infrastructure giants, or the explorer Marco Polo who traversed continents from Venice to China and altered siege warfare tactics with gunpowder, and Galileo whose scientific footprints forged more than just a cultural impact.

And we celebrate contemporary Italian-American ‘cultural icons’; the two Franks, Capra and Sinatra, Fellini, De Sica, Pirelli, Enrico Fermi, Alberto Moravia, Joe DiMaggio, Henry Mancini, Vince Lombardi, Yogi Berra and Joe Montana or Andretti, Zamboni, Rudy Giuliani, Mario Cuomo and Leon Panetta.

Is it an odd observation on my part that the aforementioned Italians and Italian-Americans do not carry deserved cultural weight in the media or in films? Hollywood and the mass media insist on ignoring centuries of precise Italian culture by grossly perpetuating demeaning and inappropriate images of Italian-Americans as stereotypical swarthy mafia-types such as the defaming ‘Vinnie the Whacker’, and offensive typecasting of Al Capone, and fictional Vito Corleone or Tony Soprano personas—criminal thugs all.

A long-overdue recognition should be duly afforded Italian-Americans who have made this country great—recognized and celebrated by organizations like the Colombo Club who proudly strive to promote Italian philosophy by honoring those generations before us who tirelessly toiled to propel their quintessential cultural achievements to the forefront.

Images appearing with this article are provided courtesy of Rick Malaspina, author of Images of America: Italian Oakland, published by Arcadia Publishing. Images of America: Italian Oakland is available from the publisher online at www.arcadiapublishing.com or by calling 888-313-2665.

Images appearing with this article are provided courtesy of Rick Malaspina, author of Images of America: Italian Oakland, published by Arcadia Publishing. Images of America: Italian Oakland is available from the publisher online at www.arcadiapublishing.com or by calling 888-313-2665.