Within a few years of the end of the Vietnam War, the American public was treated to a series of movies portraying Vietnam veterans in the worst light possible. Starting with The Deer Hunter (1978) and Apocalypse Now (1979), to Platoon (1986), Full Metal Jacket (1987), Born on the Fourth of July (1989), and even Forest Gump (1994), Hollywood depicted Vietnam vets as drug users/dealers, rapists, murderers, deserters, suicidal crazies or just plain stupid. But while the American public was having their opinions formed by Hollywood, little did they know they were flying around the country on commercial airliners with at least one, often two, and sometimes three Vietnam veterans in the cockpit.

In his first book, Vietnam to Western Airlines, Vietnam veteran and Lafayette, CA resident, Bruce Cowee, presents an oral history of the air war in Vietnam, which includes the stories and photographs of 36 pilots who all had one thing in common—after returning from Southeast Asia and separating from the service, they were hired as pilots by Western Airlines. As the chapters begin, Cowee tells his story and introduces us to each pilot, all of them volunteers who served honorably in Southeast Asia and, in most cases, never knew each other until they came home and went to work for Western Airlines. Each of the pilots featured in this book is the “real thing,” their stories spanning a nine-year period from 1964 to 1973, covering every aspect of the Air War in Southeast Asia. These 36 men represent only a small fraction of Vietnam veterans hired as pilots by Western Airlines, with some of their compelling stories having never been heard before, not even by members of their own families…until now.

The stories in Vietnam to Western Airlines include everything from heart pounding, edgeofyourseat combat, to the human-interest and even comic events that often happen in war. Through it all, there is an underlying theme: a group of young men in their 20s, thrust into situations of incredible excitement and danger, given an awesome amount of responsibility, and responding with performances that defy any measure you could come up with to evaluate them, only to return to an unappreciative and often hostile home front. It all makes an annual flight simulator evaluation or an FAA check ride seem pretty ho-hum in comparison.

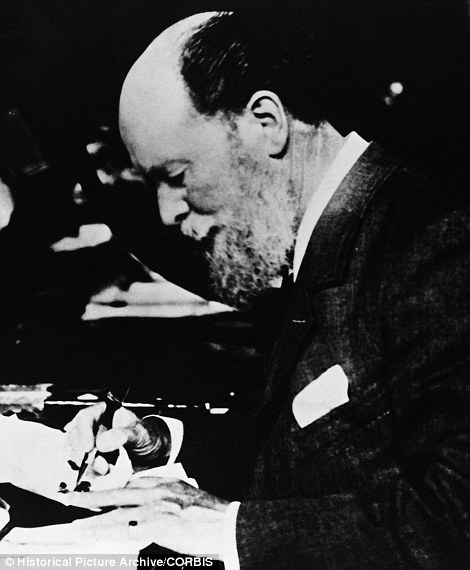

Cowee was born in Berkeley, California in 1945 and attended Berkeley public schools and the University of California, Berkeley. His road to Vietnam began as an Air Force ROTC cadet, and he still talks about filing a claim for combat pay for his last two years at CAL in the mid-60s! After a year in Vietnam and three years at Travis AFB, California, flying the C141, Cowee separated from active duty on July 1, 1972 and was hired as a pilot by Western Airlines on December 12, 1972. After Western’s merger with Delta Air Lines on April 1, 1987, he flew for an additional 17 years and retired from Delta on June 1, 2004, as a Boeing 757/767 Captain, based in Los Angeles.

Cowee’s flying career began with Vietnam and ended with 9/11, where he departed Boston on a “redeye” to Las Vegas, six hours before the hijackings. Flying New York layovers the whole month of October 2001, the crew could see the eerie dull glow of the fire that still burned at Ground Zero from nearly 100 miles away as they flew at night from Atlanta to LaGuardia. It was described by some as similar to a blast furnace at a steel mill but as Bruce recalls, “it was truly the devil’s work,” and a sight he will never forget.

I got the chance to sit down with Bruce Cowee, an extraordinary man whose healthy exuberance and boyish good looks surprised me. I realized I, too, had bought into the Vietnam veteran stereotypes, and was happy to be set straight on how these young men, no older than my own son, followed the orders of their government, completed the tasks they were sent to do, and, if they were lucky, made it home where their skills and training kept an unbeknownst public safe, 36,000 feet in the air.

ALIVE Magazine: What is Vietnam to Western Airlines about?

Bruce Cowee: The book is real history — living history or oral history, written by those who experienced it. I like the quote, “History is only history if it is accurate, and it is usually best told through the first-person accounts of people who were there.”

AM: What did you hope to accomplish with this book?

BC: I can think of at least five things, and as the time has passed, the importance of this book seems to grow.

- The book tells the unvarnished truth of each author’s experience in Vietnam, a particular mission he flew or of his overall mission while he was there. Often it includes his thoughts about the way the war was conducted. The bottom line is that each of these men was a volunteer who served honorably when his country called, and no matter what he might have thought of the war or of the politicians who managed every bit of it from Washington, he was proud of his service.

- The book is dedicated to and serves as a tribute to those who served and couldn’t come home to tell their stories.

- The book is also a tribute to this particular group of men who came back from Southeast Asia and found themselves together as pilots for Western Airlines. They navigated an unappreciative and often hostile home front and, for the most part, never told their stories or talked about Vietnam except when amongst their closest friends who, more often than not, were fellow veterans.

- The book tells the stories of a group that was a fraction of the Vietnam era pilots who came home and went to work for the commercial airlines, living normal, productive lives. It makes a good start at attempting to change the stereotypes of Vietnam veterans as perpetuated by Hollywood and the media. One might think such stereotypes would have changed, but that was not my experience talking to a high school class about Vietnam recently and even more surprisingly, an East Coast radio talk show host who was about my age, who seemed to be stuck in 1969.

- The book, certainly unplanned by me, became a vehicle for several of the authors to tell their stories for the first time. I have received several messages of thanks for providing them a forum to tell their stories and the ability to leave that history for their children and grandchildren. The great quote at the end of the 2012 movie, “Memorial Day,” is: “The stories will live forever but only if they are told.”

AM: How did you get started on this project?

BC: I’ve always been a history buff, yet I think it was a bit of a surprise to me when I was hired as a pilot by Western Airlines in December 1972, that my class of 30 was about 90% military pilots, mostly Vietnam veterans, and nobody talked about Vietnam.

When I was assigned to fly out of Western’s San Francisco pilot base in early 1974, as a second officer on the Boeing 737, almost all of the first officers I flew with were Vietnam veterans. Most of them had been hired in hiring cycle of 1968 – 1969 and some had just returned to work after a furlough of over 2 years. A good number of them still flew in military reserve units, and all services and all aircraft types were represented. For me it was like being a “kid in a candy store,” being live at the History Channel before it even existed! I had incredible access to a group of the most interesting men imaginable, and the unique work environment made it perfect for me. We would go out on a three or four day trip together, working in a cockpit where we sat two to three feet away from each other, hour after hour, then often spend time on our layovers together having meals and visiting the local spots of interest. We often spent more time together in a month than we did with our families.

I always tried to bring the conversation around to the military and Vietnam and found that some of the guys were more willing to talk than others. I learned the right questions to ask and became a good listener, so before long I was hearing the most fascinating stories and basically filing them away for some future project that hadn’t taken shape yet.

The experience I had on my return from Vietnam had a huge impact on me and planted a seed that I needed to do something positive and constructive to counter that experience. With my interest in history and my incredible and unique access to this group, I wanted to pay tribute to Vietnam veterans in general and this group specifically, with the common thread that these men all served honorably in Southeast Asia, and for the most part didn’t know each other until they came home and went to work for Western Airlines.

That was what started this project, but it wasn’t until years later, after Western merged with Delta Air Lines, that I got serious about trying to collect these stories and think about putting a book together. As we got to the mid-1990s, a sense of urgency emerged as this group was starting to retire at a pretty rapid rate, so most of the stories were written in that time frame. Collecting the photos was another major project entirely.

AM: How did you want to tell your story?

BC: This book was never intended to be about me. It only gave me an opportunity to tell a pretty interesting story about my experience, a young man who came of age in the 1960s and was faced with the decisions that every draft-eligible 18-year-old faced. The story of growing up in Berkeley, California and being an ROTC cadet at the University of California from 1962 – 1966, entering the service and then returning to Berkeley after Vietnam in May 1969, is a piece of the “living history” that is this book. That part of my story is told in just a part of the Introduction. The book is about the 36 men who wrote their stories (one wrote two stories, hence 37 chapters). I do not claim to speak for them, and I know that their politics are all over the map, but there is one thing for sure — they all served honorably and are very proud of that service.

AM: What do you mean about negative stereotypes of Vietnam veterans?

BC: There is a section in the Epilogue that addresses and corrects a long list of “statistics” and misconceptions about Vietnam veterans. Hollywood got things started right after the Vietnam War ended with a series of movies depicting Vietnam vets in the worst possible way. When I had the opportunity to speak to a high school class about Vietnam a few years ago, I found that old movies are still the source of most of their thoughts about Vietnam vets, and their history books do little more than glorify the 1960s protest movement. This book presents a different and more accurate picture of what the majority of Vietnam veterans did when they came home. They used the GI Bill to go back to school, they went back home and got on with their lives, and in a lot of cases, pilots included, used the training they received in the military to go on to have very successful civilian careers. A number of them, including Colin Powell, Norman Schwarzkopf, John Jumper, Anthony Zinni, and Carl Mundy, stayed in the military, went on to become 4 star generals, and had very successful careers. They passed on the lessons of Vietnam to the next generation of military officers.

AM: What are some of the interesting statistics you learned that we might find surprising?

BC: Vietnam veterans represented 9.7 percent of their generation, and 97% of them were honorably discharged. 91 percent of Vietnam veterans say they’re glad they served, and 74% say they would serve again, even knowing the outcome.

According to a VA study, there is no difference in drug usage between Vietnam veterans and nonVietnam veterans of the same age group, and Vietnam veterans are less likely to be in prison. 85 percent of Vietnam veterans made successful transitions to civilian life.

A common belief is that most Vietnam veterans were drafted. In fact, two thirds of the men who served in Vietnam were volunteers.

Another common belief is that a disproportionate number of African Americans were killed in the Vietnam War. In fact, 86 percent of the men who died in Vietnam were Caucasian, 12.5 percent African American, and 1.5 percent other races. These figures are proportionate to the racial makeup of the country at the time.

It’s commonly believed that the war was fought largely by the poor and uneducated. The fact is that servicemen who went to Vietnam from well-to-do backgrounds had a slightly elevated risk of dying because they were more likely to be pilots or infantry officers. Vietnam veterans were the best-educated forces our nation had ever sent into combat, with 79% having had a high school education or better.

My favorite statistic is about Vietnam “wannabes.” According to the August 2000 census count, there were just over one million Vietnam veterans still living. In the same census, the number of Americans claiming to have served incountry was nearly 14 million! More than 90 percent of those claiming to be Vietnam veterans are not! I find it most interesting that so many want to claim participation in a war we have been told was so unpopular. My recommendation is the same one I gave the English teacher at the high school where I spoke: Ask to see a DD Form 214, and that should settle the issue.

AM: Are you bitter about the treatment you received upon returning from Vietnam?

BC: Bitter is not the proper word, as I have never felt bitterness. I am only speaking for myself when answering this question, because I would never presume to speak for anyone else in this book.

I am certainly disappointed, and I think the word “annoyed” would be better to describe how I feel when I hear the old stereotypes passed along as if they are the truth. When I came home, I still had close to three years left to serve in the Air Force, so I went on and spent those first years back in the company of men with similar backgrounds. Then at Western Airlines, I was also in an environment surrounded by men with similar experiences and backgrounds, and although it wasn’t talked about much, it was right under the surface.

I truly felt bad about the incredible travesty that took place at the Oakland Army Terminal on almost a daily basis back in the late 1960s and early 1970s. The Army troops who were returning from Vietnam flew into Travis AFB and were taken by bus to the Oakland Army Terminal where those separating from the service out-processed and walked out the front gate as civilians. Many were either draftees or those who had enlisted for two years and were probably an average age of 20. About 24 hours out of Vietnam, they faced the mobs of protesters, glorified in today’s history books, who threw tomatoes and rotten fruit at the buses and then made them walk a gauntlet as they headed for buses to the Oakland or San Francisco airport and a flight home. Travesty is probably not an adequate word to describe this, but if you’re looking for reasons why a lot of Vietnam veterans have never talked about their war experience, you don’t have to look far.

AM: What has been the response to Vietnam to Western Airlines from the pilots who’ve shared their stories?

BC: It’s been pretty amazing. The overwhelming thought that has been expressed is a big “thank you, for letting us tell our stories, and “congratulations” for having the perseverance to see this project through to the end and for making the commitment to do it in a first class manner, in a beautiful book they will be proud to pass along to their children and grandchildren.

It has been a pretty emotional time, as I have had several of the authors tell me that they never would have put their stories in writing or bothered to search for their photos and put them together in this way. As a general rule, this is one of the most private groups of men when it comes to sharing their Vietnam experience, and I know from working with them that they seldom, if ever, talked about Vietnam over the years.

I have been told by four of the authors that they never would have told their stories if I hadn’t approached them, and they told me they wouldn’t have done it for anyone else. That is probably the most humbling part of this whole experience. There were several who had such compelling and “life changing” experiences in Vietnam, and those stories to tell, that they were just waiting for the right “vehicle” to come along and someone they could trust not to misuse their stories. One friend in particular looked me in the eye and said he thought long and hard about telling his story and only decided to do it because I was his friend and he trusted me to “do this right.” More than one told me they would write something, then told me they sat down to write and couldn’t do it, so I ended up interviewing them, taking notes, writing the story and then sending it back and forth several times until they were happy with the result. I suppose that is why I use the words “honored and humbled” more than once in the Preface and Introduction to the book. It has been a tremendous responsibility to be entrusted with these stories and I couldn’t be happier that the book is finally in print.

Probably the most incredible reaction came from one author in particular who told me he had never told his story and was quite surprised that I even knew about it when I approached him, as he couldn’t figure out who could have known and given me his name. He had told his wife a brief version but never told his children and they had never seen his photos, which are on display for the first time. Another universal truth that emerged: every author who received a decoration or award for a particular mission never mentioned it in his story. It was only my asking about it that got them to tell that part of the story. Not wanting to appear to be bragging or engaging in self-promotion was the common denominator, and there are several stories where decorations should have been and most likely were involved but were not mentioned. When I asked, I was told that it wasn’t important.

The most poignant message came in an email we received on the website when a very senior, retired Western Airlines Captain sent the following: he was hired in the early 1960s, several years before the first Vietnam veterans were hired by Western. He said as he looked down the chapter index that he had worked with most of them over the years, and he had never heard one of them talk about Vietnam. He was anxious to read the book and hear their stories for the first time. That says it all about this group.

For more information, including media interviews and book orders, visit www.VietnamToWesternAirlines.com.