Napoleon Bonaparte, said to be the greatest general of all time, must have mentally recoiled when he was forced to yield victory to The Turk in a high profile chess game.

The French General had already marched his victorious legions and cavalries across Europe, and had won over the hearts and minds of many nations. The conqueror was yet to experience the Russian defeat in 1812 and Battle of Waterloo against the Duke of Wellington in 1815. But now Bonaparte tasted bitter defeat against The Turk, perhaps a prelude of what was yet to come.

So, with his multitudinous battles won, intricate warfare tactics memorized to perfection and the world’s veneration as the greatest military strategist who ever lived, Commander Napoleon presumed he could outplay The Turk at a game of chess. Poised to win, he mentally strategized to his endgame, but it was The Turk who checkmated him and took the glory on that memorable day in 1809.

It may not have been so devastating to Napoleon’s ego that the general had forfeited a sure win to a chess grandmaster, but the superb military strategist had lost the game to an automaton—a mechanical machine!

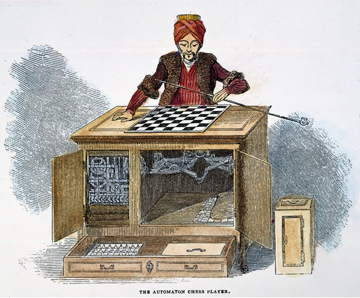

The automaton known as The Turk, debuted in 1770; the brainchild of an Austrian inventor named Wolfgang von Kempelen. He designed and created the mechanical device on to impress the empress of Austria-Hungary, Maria Theresa, and her Royal Court. The automaton was in the form of pipe-smoking man, dressed in a robe and turban, seated behind a credenza on which sat a chessboard. Inside the credenza was a series of intricate clockwork gears, cogs, rods, magnets, pantographs and peg boards.

The Turk, as it became known, made brilliant chess moves against all challengers, including Bonaparte, and won nearly every game it played, leaving onlookers and challengers alike, awe-struck. While Kempelen declined to allow anyone to physically touch or examine the automaton to discover whatever secret might exist as to how it worked, he went to great lengths to “show” that the device was, indeed, a true automaton, acting “independently of outside manipulation.” He would open two front and two rear doors, first one side and then the other, exposing the inner workings of the device, and would illuminate those workings by holding a lighted candle behind them in order to prove that it was, in fact, a machine.

The Turk attracted attention throughout Europe and even in the new nation of the United States of America, as even Benjamin Franklin, a known chess devotee, reportedly played The Turk (and lost the game) in about 1783. The Turk, the mechanical automated chess player, continued to challenge world class chess masters and notable world figures, for over eight decades in salons and on stages of two continents, until the machine was lost to a fire in a dark corner of the Philadelphia Museum.*

A MODERN-DAY TURK

It would not be until over a century later when a Man vs Machine game would again gain attention. The Soviet grandmaster, Garry Kasparov, lost to a chess-playing machine in 1997.

IBM built a mainframe computer named “Deep Blue” that played a series of tournament games with grandmasters. When the world champion Kasparov eventually yielded defeat to Deep Blue, it was rumored that the moves may have been manipulated off-site by Bobby Fischer. It was not true.

CHESS HISTORY

Circa the 6th century AD, the board game ‘Chaturanga’ emerged in India. It is thought that the game of chess, that required moves on alphanumerical positions, with 64 squares of alternating tones, evolved therefrom. The revolutionary board game was perfected by Indian mathematicians, and a fable tells that one such man Sessa, challenged the mighty king.

When the ruler of the kingdom asked how he could repay the mathematician, he answered. “Lord, place one single grain of rice on the first square, and double the quantity of each square as you proceed to the final 64th square, continue to double the rice kernels as you go.” Fair enough, thought the king.

The king of the vast domain was no match for the shrewd mathematician, Sessa, who understood the incremental succession as each square doubled the amount of rice through exponential sequences. Halfway through the process of counting the grains of rice in the kingdom’s massive granary, the grain master realized there was no more rice.

By the time the 64th square of the chess board would have been virtually heaped with rice, it would have been two billion times as much as on the first square. If half the board of only 32 squares, half of the total 64, was completed by doubling the amount of rice on each of the squares, it would exceed today’s estimated annual global rice production.

The moral fable of the king’s rice granary tells of exponential progression problems with the use of a commodity, such as rice or wheat, and a chess board, and how the Indian mathematician, rich with the rice, became the new ruler of the entire kingdom.

The earliest game boards would have been red and black, and the chess pieces were carved of ivory; elephants, chariots, horsemen and foot soldiers. Chess would have been played as a game of military strategy in simulated battle, with intricate field maneuvers that may have foreseen disaster.

Some evidence points that the game may be thousands of years old. It is thought that small carved objects, found at Indus Valley archaeological sites in India, may be circa BC 2000. Silk Road Traders carried the chess game to Persia, Mongolia, Siberia, Byzantium Turkey, and Ethiopia; later Muslim invaders introduced it to Iberia.

The lead chess piece ‘Raja’ changed to ‘Shah’ in Persia, meaning king. In the Middle Ages the board pieces evolved to King, Queen, Bishop, Knight. The Knights Templar played chess, and every good knight was expected to know how to play. By the 13th century chess was played for money; the gambling lasting for days.

In the 17th century, Giochino Greco was the first professional chess player. He wrote the book on tactical traps, checkmating patterns, and is said to have perfected the endgame. When tournament games required time limits, the hourglass was used. In the 1980s, when a player contemplated one move for nearly three hours, games were timed with digital clocks.

In Marostica, a medieval town in Italy’s Veneto, a human chess game is played in September of every even-numbered year in the middle of the piazza. Human chess pieces, dressed in full medieval regalia, with caparisoned horses, move on the marble board in the town square as plays are called.

And, chess boards can be some of the highest priced luxury items; made of precious metals and imbedded with diamonds, emeralds, rubies and pearls. Two such chess sets sold; one for half a million dollars, the other for more than $9 million.

In the 1970s, chess championships were heralded as international events. One such tournament propelled the ancient game of chess to the world stage; grandmaster of the West, Bobby Fischer, crushed the Soviet Bloc grandmaster Boris Spassky during the Cold War.

BOBBY FISCHER

Bobby Fischer, one of the world’s greatest chess players, was a child prodigy; said to have had an IQ of 187, head and shoulders above Einstein’s 160. He joined the Manhattan Chess Club at 12, was champion by 13, and grandmaster before 15. He learned by playing games against himself.

At 16 Bobby Fischer published his first book on chess. At 20, he won 63-64 championships; the only player to achieve a perfect score of 11/11 in the history of tournament play. From the age of 23, Bobby Fischer won every chess tournament for the rest of his life.

The undefeated boyishly handsome grandmaster was a rock star. The grandmaster was enormously rich. The grandmaster challenged the world’s greatest chess players, but the grandmaster was becoming eccentric, cynical, rude, hateful, demanding, bad-tempered, socially inept, and ferociously Un-American. He joined a religious cult.

Fischer, even though his parents were Jewish, became a raging anti-Semite, spewing hatred against Jews and America at news conferences; his vile remarks stunning listeners over international airwaves. After 9/11, he praised the terrorists, and even wrote a letter to Osama Bin Laden calling for the destruction of the United States. Fischer had dipped into moral oblivion.

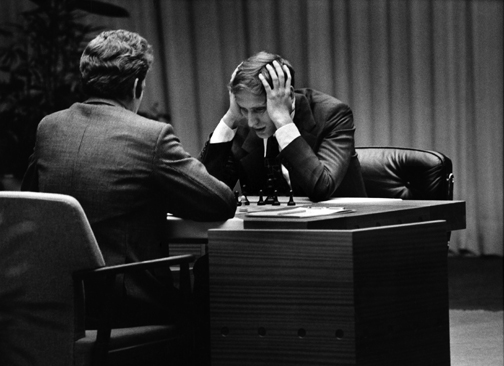

But the Golden Boy was once great; the masterful maverick’s name was on the lips of every American and Russian alike, when he flew to Reykjavik, Iceland in 1972 for a veritable chess mano-a-mano in the much-publicized “Cold War Confrontation.” It was the nail-biting event of the century; Fischer versus the Soviet Boris Spassky, the undefeated grandmaster. Fischer won.

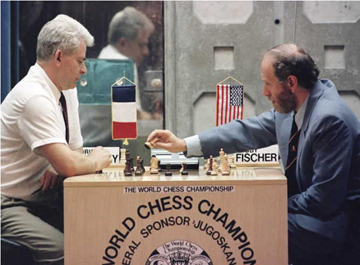

Years later in 1992, grandmaster Bobby Fischer accepted a rematch invitation to compete in the former Yugoslavia, then under U.N. embargo. The State Department warned him not to go. He earned a huge purse of which the IRS wanted a large chunk. Fischer refused to pay up, and chose not to return to the States. The State Department revoked his passport for tax evasion and he became a fugitive. He lived in Hungary, Germany, Iceland and the Far East.

Fischer’s hatred and anti-Semitism may be explained because Bobby Fischer’s physician mother conceived him out-of-wedlock; a social stigma at that time. In the 1950s, an FBI probe revealed Regina Fischer’s anti-American and Communist activism. Another probe by journalists in 2002 revealed that Bobby Fischer’s putative birth father was Hungarian physicist Paul Nemeny, not the man to whom his mother was married.

Fischer’s rabid anti-Semitism is inexplicable as both his parents were Jewish. His mother was a Swiss-born wartime refugee, and avowed Communist who lived in Russia before New York. Bobby’s birth father occasionally visited his son, but never admitted paternity, and sent periodic child support payments.

Bobby was an introverted lonely child, spending much time alone with his sister in their Brooklyn apartment. The boy discovered the challenge of chess when he bought a set at the drug store under his apartment building. His mother placed an ad in a newspaper seeking “someone to play chess with her son.” The man who taught the boy wonder the game, mentored him to success, and became his only father figure was later publicly maligned by Fischer “as a Jew snake.”

After winning the world title as grandmaster, the once-unstoppable chess prodigy slid into the depths of self-destruction and obscurity when the egomaniacal fugitive spewed unbridled hate for Jews and Israel, and denying the Holocaust. He ranted at a news conference in Iceland when seeking asylum. While belittling his former tutor and mentor with anti-Semitic vile comments, reporters walked away disgusted.

Even though the once- brilliant Bobby Fischer was grandmaster of strategy, and able to foresee results of his endgame, his last days on earth, and post death events, could not have been planned worse.

Bobby Fischer died of renal failure in January 2008 as a lonely, bitter man. His estate was valued at $2 million. His nephews, the executors, paid the owed taxes to the IRS. A bitter fight ensued as to who would inherit the remaining money.

A young girl in Japan, claiming to be his daughter, won the right to have Bobby Fischer’s body exhumed. DNA testing proved she was not his child. His Japanese wife claimed the rest of the money and sued the estate.

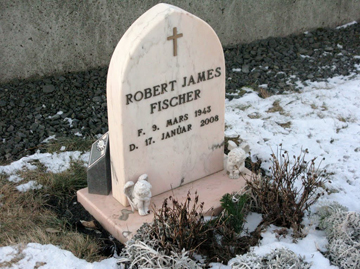

Officials returned the once-heralded grandmaster’s body to the ice-covered ground in a remote graveyard on the shadow less island overlooking the vast barren Icelandic tundra. The near-forgotten grandmaster genius, who had taken the chess world by storm, now rests in an Artic windswept treeless place, under a lone stone grave marker incised with the once-iconic name; Robert James Fischer—1943-2008.

*You can learn more about The Turk in the book, The Turk, by Tom Standage