A DAY IN SAN FRANCISCO’S STORIED CHINATOWN

Golden tiger images are everywhere in Chinatown, 2010 is a very lucky year – not only the Year of the Tiger, but the Year of the GOLDEN Tiger, that only comes every sixty years, as explained to me by my kind friend Shujuan Liu – Susan – who accompanied me on my tour of San Francisco’s historic Chinatown. Each twelfth year, according to the ancient Chinese horoscope, one animal is the annual representative icon: horse, dog, rabbit, pig, snake and the dragon among them.

Susan lives in Danville and came from Beijing in 1998 with her husband and son. Susan gave me new insights into the traditions and culture of China, of which I not was aware, even though I had visited our own San Francisco Chinatown hundreds of times. This time was different – I looked up, out, and around, rather than peering into gift shop windows at paper parasols, bamboo back-scratchers, battery-operated caged singing birds and mechanical crickets – or searching for dim sum.

So, we ventured into Chinatown at Grant and Bush Streets, through the imposing blue-tiled Dragon Gate, a gift from the Republic of China in 1969, defining the entrance to the locale—the fulcrum of Gold Rush history. I looked up the storied gradient street named Grant with fresh eyes—celebrating the Year of the Golden Tiger—reminded everywhere of the extra-lucky year, re-enforced by images of leaping, crouching or growling golden-striped cats. Tigers jumped stealthily from store windows, waved on gonfalons, crawled on rooftops, slumbered on embroidered pillows or roared from sweetshops, calling us to taste lotus seed-filled moon cakes at the Eastern Bakery, or to buy paper tiger kites to catch the Marina winds blowing by the Golden Gate, their long tails streaming and silhouetted against the sun.

Yes, it is the year of great fortune—the year of the striped ‘wang’ face of the golden tiger, an auspicious period that comes around only every sixty years. For the lucky ones, born in the Year of the Tiger, it promises courage, fearlessness, tenacity, purposefulness and the burning desire for adventure. We, the tiger and dragon girls, walked into Chinatown, into the past; into timeless tradition and into the culture that is a vital historic backbone of Old San Francisco.

CHINATOWN – THE EPICENTRE OF THE CITY’S HISTORY

The face of present day Chinatown, is just a little over one hundred years old, being totally rebuilt after the 1906 earthquake, with an incongruous mix of Edwardian structure with applied Chinoiserie details, even though the original neighborhood was established before the Gold Rush in 1848. The first Chinese immigrated to San Francisco when a woman and two men arrived on The Eagle – the same year that Sam Brannon announced the discovery of gold at Sutter’s Mill, in the present-day open space gardens called Portsmouth Square. Today, the wisteria-laden pergolas shade chasing children, near-motionless Tai Chi exercisers, and baseball-capped old men playing elephant chess with an audience of bewildered tourists, as the crack-and -bamboo tiles clink by intense Mah Jong players.

|

|

By July of 1853, Old St Mary’s Church, the first cathedral in California and the tallest building in town was built on the corner of Grant and California Streets. The church’s foundation granite was quarried and cut in China, and the New England red-fired bricks came around Cape Horn on the same ships as daring prospectors, in search of God and gold. With the Gold Rush, came men with money to burn and for the money, came the women to earn. The first all-Chinese school was erected in 1859, to educate the children of immigrants, who came by the thousands from the open port of Canton in the southern Guangdong Province thereby establishing the Cantonese language in most resettled communities. For a decade, workers flowed into San Francisco and in 1870, California passed a law against the importation of women for illicit purposes, and human trafficking trade went underground.

The rush for gold lead to the need for transport, and the construction of railroad networks created an influx of laborers and San Francisco was the magnet for new immigrants from the across the China Seas. Chinatown took on a pulsating life of its own, a vibrant, bustling epicenter of exotic foods, haunting music and historic significance – an ‘island’ of an ancient culture thriving in the heart of The City.

Chinese lore dictates that evil travels in a straight line, so we followed the labyrinthine side streets where the waft of incense leads one to the mosaiced façade of the 1852 Taoist Temple Tien Hou, and the city’s oldest Buddhist praying place, the Norras Temple on the two-block Waverly Place – the Street of Painted Balconies. The short street, parallel to Grant, is the un-touristy real Chinatown, where dry cleaners, insurance agencies, a one-chair barber shop (who also repairs radios) and a funeral parlor that takes care of Chinese San Franciscans. Waverly Place is the locale of Dashiell Hammet’s 1947 story Dead Yellow Women, and for many movies, including Indiana Jones.

Funerals are unjoyous events, but when one must go… Chinatown is as good a place as any! The procession follows from the Green Street Mortuary up Stockton and Columbus Streets, preceded by a brass band and a convertible bearing the deceased’s larger-than-life photograph image, followed by the hearse and a cortege of mourners. For under a dollar, a pack of handmade memorial papers, tinged with gold, can be bought and burned in the temple as tribute to Buddhist or Taoist ancestors, or kept as a beautiful souvenir to remember the sense of place.

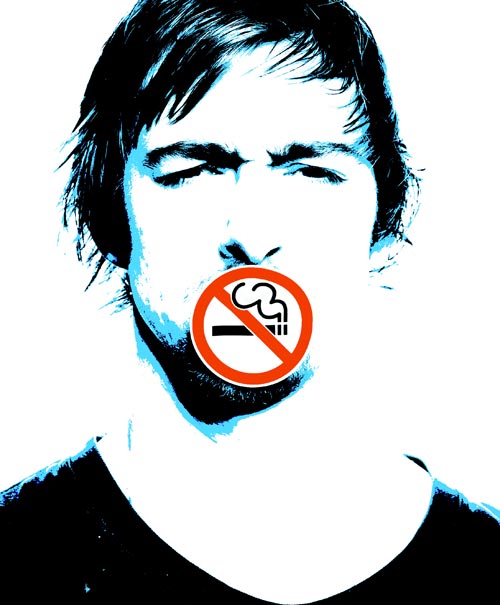

Susan and I moved up Grant Avenue to the produce markets where fruits and vegetables – bok choy, spring onions, mushrooms and slender purple eggplants, basked in boxes on the sunny street or hung, sun-steamed in tight plastic bags, over sidewalks. I really wanted to visit the herbalist shops, especially with Susan who could translate for me, and check out the herbs and animal parts—strange to westerners’ tastes—but inextricably tied to ancient Chinese culture. Well, I learned something new and unexpected. Susan, being from Beijing, could read the written Cantonese language perfectly, being the same as Mandarin, but when she asked questions, they could not understand one another and shopkeepers looked at her in askance. She explained that Chinese speakers find the lingua franca of English, the best way to communicate, albeit Chinese written characters are universal. When Mayor Newsom visits Beijing, his valiant attempt at Cantonese falls short, and no one understands him.

We entered the crowded herbalist shop, where almost everything edible was dried. Susan explained that because of China’s lack of refrigeration for centuries, most foods were dried, dehydrated and preserved, however, now, even with refrigeration; dried goods are preferred because of the intensity of flavor. We walked around the shop, I with finicky trepidation, finally coming to the realization what foods I might have eaten on my last trip to China. I squirmed.

We roamed the shop curiously reading signs and prices. “Susan, what are those things?” I asked about a very strange selection of rows of apothecary jars filled with dried, black shiny tongue-shaped things priced at $960 and a whopping $2,160 per pound. The elongated shriveled grey things, marked at $5,400 per lb, fascinated me. She read the tags. The black shiny things were deer tails at $2,160 per lb and the dried grey things at $5,400 per lb were very pricy ginseng. The wild ginseng was only $2,200.00 per lb, and the dried sea horses were a bargain at only $65.00 per lb. “The tongue-shaped things are deer tails, probably used for natural medicinal purposes; the ginseng is used for many Chinese ailments,” Susan explained.

I decided that I would live with my ailments, if and when, they came to me – the finicky eater that I am!

We moved on to an artistic arrangement of platter-sized dried brown shiny mushrooms, called lensi at $68.00 per lb. The still-life appealed to my sense of artistic incongruity and I asked the shopkeeper if I could take a photo with my camera. “No, it is our policy to forbid cameras.” The shopkeeper warned. She had not said a word about iPhones, so Susan snapped a photo and emailed it to me. Ah! The insightful understanding and use of one’s own phone technology, in the time of need! (I reminded myself of the potential joys of iPhone ownership).

We read more labels; dried grey shark fins were $215.00 per lb and the sinewy yellowy fish intestines and stomachs ranged from $280-$800 per lb – yum. The cardboard-thin, skeletal flat dried spread-eagle ducks, heads cocked to the side, still intact with feet and thin bony ribcage, must have been a bargain, as they were selling like hotcakes as customers yanked the flat ducks off the wall. I stopped for a moment to visualize the duck flattening, then I quickly purged the thoughts from my head.

I pondered the medicinal mysteries and wondrous results, from herbs and animal parts, for both mind and body, and I learned more than I ever needed to know about fresh-frozen deer tales, red deer antler velvet, bear bile, ox-gallstones, sheep placenta and yak pizzles (viable competitors to OTC tiny blues). Strange, I thought, I never had the need to learn of the exotic ingredients or herbalist uses, until Susan interpreted the signage for me—and through the wonders of googling—I learned their remedial and therapeutic miracles.

COLOR, FORM, BALANCE AND GOOD LUCK

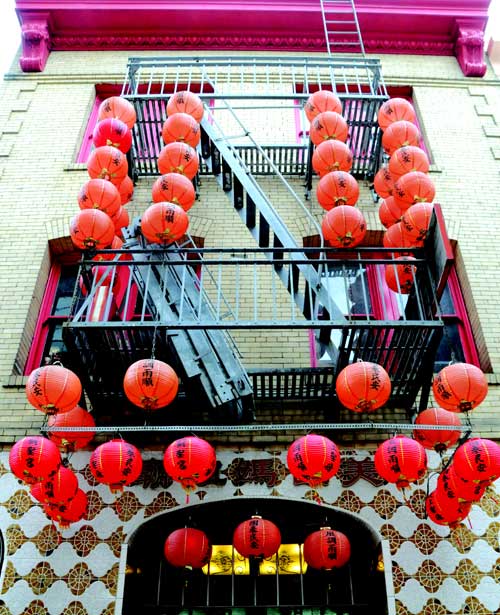

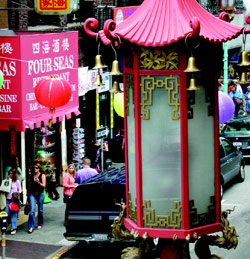

Ornate Dragon lampposts – turquoise and cinnabar, surmounted with twelve-belled lanterns and crawling tendrilled dragons, since 1925 have lighted the gradient pathway to Chinese cultural tradition. Chinatown’s architecture is a veritable chop suey of odd styles; Edwardian structures encrusted with applied decoration—bright colored painted balconies, their fire-escape ladders hugging facades, entangled in waving red Chinese and American flags, vying with rotating pinwheels, to catch the breeze.

Pagoda-style edifices interject balance and symmetry from the axis, among plain buildings, standing stalwart and four-square in timber-frame structures with pillars and beams—wood equaling life—doors and windows to the front, heavy tiled roof on toukung support brackets, corbels holding cantilevered arms on rooflines where gently curved corners, like bird wings, fly out from swooping eaves. Bold reds, gold, greens—lacquered on cedar-wood—and blues compete with the sky’s colors. Myths tell that water lilies prevent fires, dragons crawl on tiered overhangs, and phoenixes, adorned with spirals and swirls, confuse evil spirits—tasseled lanterns, bells and banners entice harmony with bats and peacocks painted iridescent green.

The Chinese feng shui living space layout is a cosmological scheme arranged in the eight compass points, where the front of a house faces south to the light, and the back faces northern mountains to deflect bad energy.

We absorbed the architecture, craning our necks, and then stopped for eye-candy respite, at jewelry stores to check the modern designs of today’s China, that appeared to have taken on a more definitive ‘European’ style, since I shopped in China thirty-seven years ago. The designs were more contemporary than yesteryear’s pre-capitalist styles when I spent time in China in 1981. We stopped for lunch and I had a chance to ask Susan about her music and her own jewelry designs.

HARMONY AND A SYMPHONY IN JEWELRY DESIGN

HARMONY AND A SYMPHONY IN JEWELRY DESIGN

Energized with a new approach of all things Chinese, I was thirsty for inside stories of Susan’s life and I quizzed her on her line of Shujuan Liu Designs, her favorite materials and sources for her inspiration.

Susan was a music teacher in Beijing, but always had the yearning to create things. She hand-colored her own black and white photographs – before color film was popular in China – and loved color-painting stones and playing with her ‘toy’ pebbles as a young child and mused that she can now ‘play’ with real colored gemstones. When Susan arrived in the United States in 1998, she worked at a Hong Kong-based fashion clothing company in Los Angeles with manufacturing in China, and her position allowed her to be involved in every aspect of the fashion industry. In order to further her expertise in the fashion world, she studied merchandising and design at Santa Monica College. Her experience and expertise took her to Lucky Gem, one of Asia’s largest jewelry companies, and with a good eye for design and a fine fashion sense, the company requested her to design a special display for their showcase front window – and, as they say – the rest is history. It led to further classes in jewelry design and she learned the subtle art of the cut and the polishing of stones and silver design work.

Susan explained the harmony of the number seven in the Western culture and the Eastern elements of coral – once alive in the sea – that signifies passion, prosperity and luck. The combining of the two, in some jewelry designs, is not only beautiful as wearable art, but also brings good fortune. I fingered my own coral necklace, the symbol for passion and prosperity, and for a fleeting moment, I felt very lucky.

When I asked her the source for stones, coral, and findings, she told me about her travels in search of special pieces. An upcoming trip to China will net her a cache of new stones, rare corals and elements to compose designs, unique to her sense of rhythmic elegance with harmony and simplicity, with corals, gemstones, and freshwater pearls. Susan also attends the Tucson, San Mateo and Las Vegas Gem and Jewelry Shows, each one a Mecca for designers in search of findings and new materials for the one-of-a- kind art, and for inspiration as she prepares a collaborative jewelry design show in October – queries: jliudesigns.info@gmail.com.

“So, Susan what do you do in your spare time?” I really wanted to ask a more Proustian question of the dark-eyed, statuesque Beijing beauty.

“I produced a documentary film called Little Shoalin Monks about six-year-old boys trained in temples to be warrior monks. I am soon on my way to Beijing, to visit my family and do research for another film about the serious lack of clean drinking water in China – that will be my next documentary,” Shujuan Liu answered with modest restrain.

We came full circle from the Chinatown assignment, to art jewelry design and filmmaking. I always believed that it was the busy people, who actually got things done. The work Susan had done in film, opened doors at the Mill Valley Film Festival, where she met Tang Wei, the star of Crouching Dragon’s director Ang Lee’s recent artistic film Lust, Caution – winner of the 2007 Golden Lion Award at the Venice Film Festival in Italy. Tang Wei, who plays the lead in the Mandarin-language film, cherishes her Shujuan Liu designed necklace, with seven branches of vibrant red coral, the symbol of prosperity, passion and good fortune.

We laughed a lot. 2010 – The Year of the Golden Tiger – is going to be a very good year.