After two Islamist terrorists attacked the offices of the French publication Charlie Hebdo, killing twelve and injuring eleven, many Americans and nearly all journalists spoke up in defense of free speech. Some people, and incredibly even a few in the media, moderated their support for this foundational value by suggesting that the satirical magazine may have gone “too far”— but those voices were rare. Mass rallies and marches followed the tragedy in a statement of solidarity. The message was clear: Freedom of speech and expression is so important to the concept of liberty, we will defend it—even if we don’t agree with the message expressed. To show images of the Prophet Mohammad as a depraved lunatic or Jesus Christ bathed in an artist’s urine, are all acceptable expressions of art or political commentary worthy of protection.

Just a few short months ago, it was the sentiment of Americans that: Freedom of expression is sacred, as they aligned with Evelyn Beatrice Hall in saying, “I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it.”

But, perhaps they meant to continue…”Just don’t dare display the Confederate Flag or print or utter the ‘N’” word” (unless you are, in some way, anointed royalty).

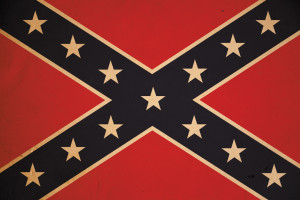

“But the Confederate flag is symbol of racism. It is a painful reminder of slavery in America, and the oppression of African Americans,” say those insisting in this latest wave of politically correct “symbolic cleansing.”

“But the Confederate flag is symbol of racism. It is a painful reminder of slavery in America, and the oppression of African Americans,” say those insisting in this latest wave of politically correct “symbolic cleansing.”

I’m not easily influenced by impassioned or mob-driven movements. I loathe faddish thinking, particularly when it is based upon ideas disconnected from fact and truth. So, aside from the blatant hypocrisy here, let’s consider the question: Does the Confederate flag truly represent what the mob claims, or is their criticism based upon something else—like their own opinions, impressions, or ignorance?

First off, the flag usually being identified as “The Confederate Flag” is really only the Battle Flag of Northern Virginia. There were actually a series of different flags for the Confederacy, each one unique to a specific period.

Now, as for what the flags actually represented in terms of its history: They represented the Confederate States of America (CSA), a collection of eleven Southern states that included Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Texas, Virginia, Tennessee, Louisiana, and Mississippi. These states seceded from the Union in 1860-1861.

The catalyst for secession was the election of Abraham Lincoln as president, who promised not to allow slavery to expand into new territories that had yet to become states.

While slavery was a pivotal issue in the secession and subsequent Civil War, the division was much more about economics than about morality at the time. And this is key point to remember when we start talking about removing symbols in some effort to re-write history. As late as 1850, slavery still existed to some degree in the North, although not anywhere near the levels that id did in the South. But this had much more to do with the climate and economy than morality. Cotton and tobacco didn’t grow well in the Northern States, so they failed to develop any large-scale agricultural industry that benefited from using slaves—so instead, they benefited from them indirectly.

Entrepreneurs, bankers and Northern slave traders were among the institution’s staunchest defenders prior to the war. In fact, between 1859 and 1860, two ships sailed to Africa every month from New York to purchase slaves. Northerners also profited greatly from slavery through the cotton trade. Entire cities in the North were created around textile mills that manufactured cloth made from cotton—cotton that had been picked by slaves in the South. In 1861, more than two billion pounds of cotton cloth was produced, much of it sold and shipped to Great Britain by New York merchants.

While slavery played a major role in the split between North and South, to a large degree, the secession of the South and the subsequent Civil War was also because of trade and tariff differences and a growing resentment felt by Southerners for what they perceived to be a largely hypocritical North—states that had been enriched by the slave industry to a large degree that now threatened to restrain future growth of the South’s industrial base.

Aside from the political and military history concerning the Civil War, it is important to realize that attitudes and standards of morality were different then. As difficult as it is for us today to accept, slavery has existed throughout history, often based upon racial differences. As distasteful as it sounds, many fellow human beings were then considered “creatures.” Both by law and cultural perspective, African slaves and likewise Native Americans, were then considered “inferior” beings.

What any rational person today would consider racism, was the prevalent attitude in both the South and North prior to the Civil War. In fact, Lincoln himself, in a Senate debate with Stephen Douglas in 1858 said, “I will say then that I am not, nor ever have been, in favor of bringing about in any way the social and political equality of the white and black races,” he went on to say that he opposed blacks having the right to vote, to hold office or serve on juries or inter-marry with whites.

Likewise, in an effort to prevent the Civil War, president-elect, Lincoln even supported a Constitutional Amendment (The Corwin Amendment) which would have permanently established slavery as a legal institution, if only the South agreed to remain in the Union. The amendment passed both houses of Congress and was signed by then lame duck President James Buchanan. Even so, the Southern States declined to rejoin the Union, citing other grievances with the federal government in Washington. (Technically, the amendment is still pending!)

Lincoln only became “The Great Emancipator” when it became militarily and political expedient—freedom for the slaves was merely a byproduct of emancipation, not the goal of it.

Furthermore, prior to the Civil War, the Supreme Court ruled in the landmark Dred Scott case that African Americans had no claim to freedom or citizenship and since slaves were private property, Congress did not have the power to regulate slavery in the territories and could not revoke a slave owner’s rights. This ruling served to bolster the South’s position and only helped to move the nation closer to division.

So, in the context of history, were those who considered African Americans “something less than human beings” evil, racists? The answer is yes… if they were aware and understood then what we accept today as the truth about human equality. But I don’t think that’s the case. Many then likely found reassurance in the Dred Scott decision of their belief that some people were of less value—less human—than others.

Indeed, could not the same argument be made today, for example, of those who deny the equal humanity of a fetus, knowing that it has unique DNA? Are today’s “pro-choice” advocates really modern day “Confederates” hiding behind yet another ugly decision of the Supreme Court?

The legacy of the Confederacy and Southern culture isn’t just about slavery any more than women and reproductive rights is just about abortion.

We live in a different time and have the benefit of progress. We should consider our history and learn from it, but none of us can reach back into time with a claim of full understanding to render judgment and now selectively punish those no longer here to explain their actions.

And in terms of our history and slavery, if a Confederate flag is regarded solely as a symbol of bigotry and hatred, how then shall we judge the American Flag?