Feature

The Inverse Village of Danville

When Randy was selected by the Peace Corps to go to Tanzania in 2006, my wife Jennifer and I hatched a plan to visit him halfway through his two-year “tour of duty.” Our goal was Two-fold—to get him out of his remote village for a while and for us to experience Africa, since we’d never been. We decided to break our trip into three segments—three days of traditional safari activities in national parks, three days in Randy’s village of Dawar and then four more days of safari to wrap things up.

As the trip approached this past fall, we read guide books and studied web-based sources to learn more about what we could expect. The abundant and amazing wildlife at parks such as Ngorongoro and Tarangire was well documented. Their tourist lodges had all the amenities—bathrooms with flush toilets, running water, hot showers and electric outlets; first class dining rooms with salads, soups and recognizable meat products; and lounges with excellent selections of good wine and cold beer. Now, that’s a vision any Danvillite can appreciate!

But Dawar was noticeably absent from the web, other than a few Christian missionary sites. We knew it was on the southern flanks of Mt Hanang, but it was not on our detailed map of Tanzania. The only nearby town shown on the map was Katesh where Randy gets his mail, does his shopping and has limited access to the internet—and that’s several miles away from Dawar. Randy’s village was clearly not considered a popular tourist destination.

Because of our unique itinerary, Randy handled most of the incountry schedule by working with a Tanzanian company named Safari Makers. We also needed help arranging our international flights. The reduced number of airline flights with tight connections, new baggage fees and restrictions, upgradeable airline seats, airport overnight stay hotels, etc. made it more complex than we could handle via the web. The professional travel planners at Danville Travel smoothed everything out for us.

The flight segments were long and we were very happy when we finally arrived at Kilimanjaro airport. That very afternoon we headed to Lake Manyara and saw a wide assortment of wildlife. We spent the following two days at Ngorongoro Crater, photographing every African animal that anyone could hope to. Even outside the main safari areas, there was always something fascinating to see right next to the road whether plant, animal or human in nature (sometimes, up close and personal). The sunsets were glorious, the lodges were comfortable,

and the food was great. It was clear this was going to become one of those “lifetime adventures.”

On the appointed day, we headed south towards Dawar. After just a few miles on route A104, the pavement ended—our first hint that we were heading away from the amenities of civilization. We endured a three hour drive over the most bumpy, dusty, narrow roads imaginable. Dust-devils swirled over our car and oncoming cargo trucks hugged the center of the dirt road, forcing us to often drive on the shoulder. It was a bone-jarring, teeth- rattling ride in our hired 4WD Land Cruiser, but our guide Welking persevered and we made it through.

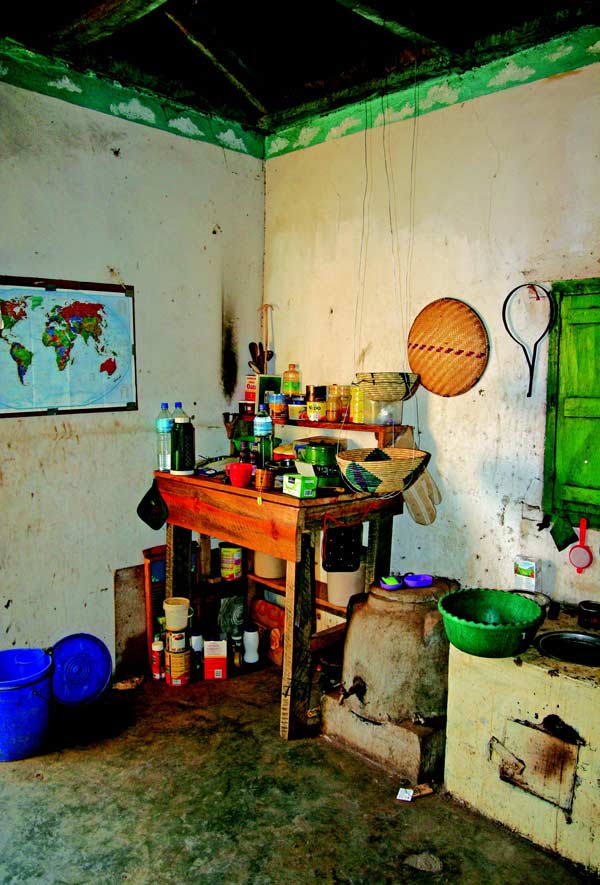

When we finally arrived in Randy’s village, we unloaded our bags and walked into his house. It was a small rectangular concrete slab with mud-covered cinder block walls and a tin roof. The reality of our situation jumped on Jen and I like a hungry leopard on its prey. We watched through the long cracks in the front door as a calf walked by outside. The only furniture was a mattress on the floor and a handbuilt book case, which doubled as Randy’s dresser. There was no electricity (the power lines stopped a few miles away when the TZ power company ran out of money). There was no running water (the community between Dawar and a nearby natural springs took most of it for their use). During the dry months, Randy joined the villagers on their trek to the springs to fill up a 5 gallon plastic container every few days, although he occasionally hitched a ride on a passing ox cart. Obviously, there was no flush toilet, no hot showers, no microwave oven nor refrigerator, etc. The only light at night was provided by a few candles. Frankly, we were shocked at his living conditions—even our most modest expectations were not met. While we’d traveled only a few hours by car, it seemed that we’d stepped centuries back in time.

Both Jen and I needed to take “a moment” and get a grip on this unexpected situation. She went outside, found a shady spot under an acacia tree and composed herself. I grabbed a broom and swept the dust and rodent droppings off the floor. Randy chased down the mice with a pair of salad tongs and ejected them from the house for our benefit (I’m sure they punished him for this indiscretion after we left).

Each of our days began with Randy boiling a pot of water over a small brazier outdoors. To maintain a hot flame, he used dried corn cobs and charcoal for fuel. From this small pot we made cups of tea, washed our faces and brushed our teeth. I was constantly reminded of emotions from my USMC survival school days—a huge difference from life in Danville, or even our safari lodges! Our trip had abruptly shifted gears from being a majestic wildlife safari to one of intense cultural interaction with tribal villagers.

|

|

|

|

|

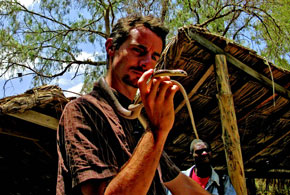

The people of Dawar and the surrounding region still share their home with a variety of “original residents.”

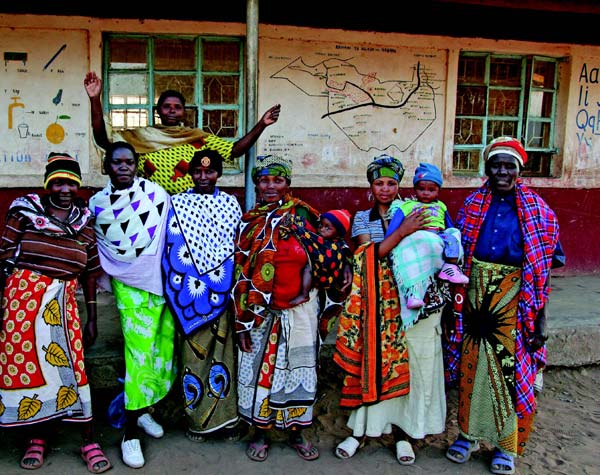

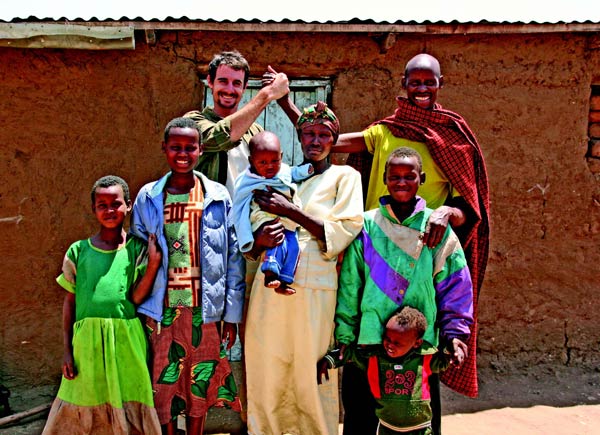

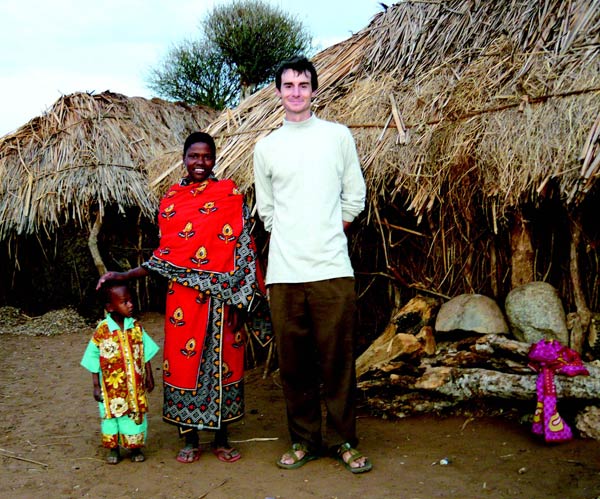

We soon learned that a few of the locals lived in better houses than Randy’s—but many were worse. This area was a tough place to eke out a living, either as a farmer or a cattle herder. Yet, as difficult and primitive as their daily living conditions are, we found the Barabaig and Iraqqw tribal people to be extremely friendly and engaging. Jen and I were welcomed with the gift of a live chicken, a considerable portion of the donor’s net worth. We were pleasantly surprised by a village-wide welcome celebration thrown in our honor the first evening. During an incredibly lively and colorful dance ceremony, we were given traditional dress costumes and made to feel at home. During the walk home that night, however, we had to mentally balance between watching the fantastic night sky, with zillions of bright stars, and the path ahead, which might harbor snakes and hyenas looking for easy prey. Based on thousands of years of tribal knowledge, villagers are aware they must fully live for today—tomorrow is not guaranteed.

Over the next two days and nights, we were ushered into many homes with the greeting “karibuni sana,” which means “you are most welcome” in Swahili. The family father or mother would motion for us to sit on wooden stools, sometimes with a baby goat nestled under it to protect it from hyenas at night. We were always served a cup of chai (hot tea) and often a meal of ugali (corn porridge) or hard-boiled eggs. A lengthy conversation would then ensue, with Randy doing an excellent job of interpreting between English and Swahili.

Randy introduced us to a wide variety of people. We met with various community leaders such as the local doctor, church pastors, Christian missionaries, school principals, teachers and business people. We also spent quality time with a brickmaker, cattle herders, farmers and ox-cart drivers. During one late afternoon stroll, we came upon the local blacksmith, who hand-made fashionable bracelets as gifts for us, working all evening to finish them.

The genuine hospitality of all the villagers was heart-rending, considering this inhospitable countryside with such scarce resources to draw from. While their material possessions are few, their spiritual wealth is great.

|

|

|

|

|

The Peace Corps is currently helping the villagers obtain funding to dig a well and to expand their basic community clinic. Also, the few relatively-wealthy villagers created an economic assistance co-op program to help others get started with businesses (the average loan is around $20). So far, it has resulted in the opening of a new butcher shop, a corn seed store and a “fast food diner” whose specialty is a mixture of scrambled eggs and grilled potatoes. It is amazing how so little money (to us) can be put to such great use in a village like this.

While Jen and I were happy to get back to a safari lodge after our three-day stay in Dawar, we were psychologically “conflicted.” We had been granted a rare and valuable experience by interacting with these rural villagers on a personal level, leveraging friendships created by Randy to penetrate the veil that normally lies between cultural strangers. We discovered that the true measure of “civilization” lies not with a society’s level of sophistication or technology, but with their human interaction and social support systems.

|

|

|

I hope that we who live in Danville will be as civilized as the Dawar folks when that 8.0 earthquake disrupts our transportation system, shreds our electric power grid, and destroys

our ability to communicate with the outside world. If our citizens overcome their personal hardships and assist each other as the Dawar villagers do every day, then we will pass the real test of humanity.

Randy has made the transition well, albeit not how we expected when the Peace Corps first signed him up. Perhaps the ultimate test for a “social services worker” is the respect given him by those he is trying to help. Randy is held in such high regard that he was inducted into the tribe as an honorary warrior during that village-wide ceremony our first day. He may be the first Chico State graduate “licensed” to carry a spear when he goes for a walk in the bush—and it’s not just for show. While this was never on the parental list of career expectations, we are very proud of him.

To assist Randy with his clinic expansion project, visit www.peacecorps.gov, click on “Donate Now”, and do a “Search by Volunteer” using the name “Fish”.

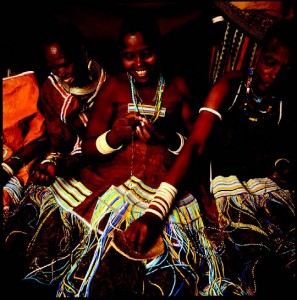

Since 1994, the founders of two American sister companies, the AMIAS Project and Another Land, have been working with the Barabaig tribe to foster cultural pride, conservation and innovation. To provide adventurous travelers with a once-in-a-lifetime cultural opportunity, Another Land offers tours where guests interact with people that live in Randy’s area (www.anotherland.com). For those who prefer assisting the tribal craftspeople from the comfort of their home, the AMIAS Project has an online gift shop with a wide range of fair-trade Barabaig jewelry and accessories (www.amias.org).

BOB FISH

Danville to Dawar: A Personal Journey

After graduating from California State University, Chico in summer 2006, I didn’t have a clue what my passion was, what I wanted to do, or who I really was. The only thing I was sure of is that I was not ready to enter the ‘real world.’ So, instead of plunging into the depths of a 9 to 5 office job, I decided to join the Peace Corps. I was finally posted to Tanzania in June of 2008 as an environmental education volunteer.

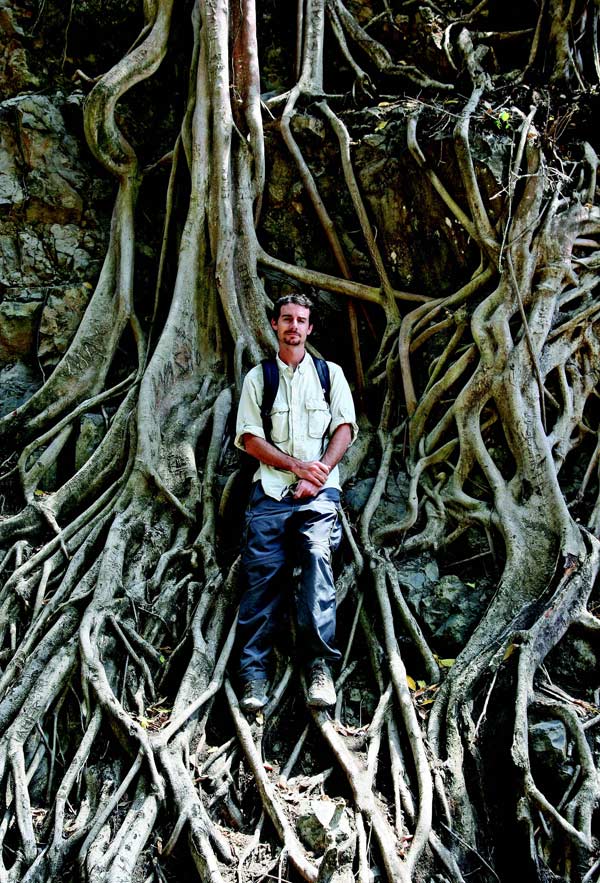

In the two year interim, I attended graduate school at Michigan Technological University, and had plenty of time to formulate expectations for my Peace Corps experience. By seeing life from the eyes of those less fortunate than myself, hearing their stories, and living as they live, I reasoned I should be able to discover the original humanity within all of us, get a glimpse of my own in the process, and figure out what I want to do with my life. There was also the allure of the simple life in a mud-walled hut, surrounded by jungled wilderness, helping impoverished people alleviate some of their problems, and, of course, plenty of time to hone my yoga postures.

In August of last year, I unpacked my duffel bag at my tiny (300 sq ft) cement floor house in Dawar, a village that is not on any map. It’s located in the Great African Rift Valley, just south of Mt. Hanang, the fourth highest peak in Tanzania. The nearest town with amenities such as electricity and running water is Katesh, about five miles east. And that town is about 125 miles south of the nearest major tourist safari destinations. It’s an inhospitable land—very arid, with thorny acacia trees strewn across the landscape.

There are two rainy periods every year—the short rains in December/January and the long rains in May/June. Crop planting and harvesting must be accomplished in those relatively short periods. Other than that, it’s very dry and dusty, with dust-devils (whirlwinds) creating a permanent haze in the sky. Located only three degrees south of the equator, the sun is very intense during the day. Other dangers lurk everywhere, especially at night. The water has parasites, the mosquitoes carry malaria, venomous snakes are scattered throughout the bush, and hyenas have killed three villagers in the recent past. Every hike into the bush country is an adventure.

Two main tribes dominate the Hanang area-the traditionally agricultural Iraqqw, and the formerly nomadic-pastoralist Barabaig. The former grow maize (corn) and beans on small plots of land near their mud huts, quite a struggle in this parched land. The latter are cattle-herders who must constantly try to find water and food for their grazing herds. Cow milk and maize are dietary staples in this area. During the dry seasons, nearly every meal consists of ugali, a porridge made of ground-up corn. It’s not tasty but it fills the stomach.

Life is still very primitive with a direct lineage that goes back thousands of years. Many families live in mud-walled huts with thatched roofs and no doors or windows. There is no electricity – candlepower rules the evening in every house. There is no running water—just large buckets that are filled up ever few days from a natural springs outlet, about a half-mile north of the village. The wealth of a man is measured by the number of cattle he owns; women by the number of children they have borne.

However, the village elders realize they must make improvements to the environment. While there is very little investment capital available in these remote “barter-based” societies, the schools, clinic, water system, roads, houses, farming techniques, livestock management processes, etc. must be upgraded to modern standards. At the same time, better health care (malaria vaccinations, etc.) has already resulted in a growing population, resulting in dwindling fertile lands and more stress on the scarce water resources. I find myself caught between two cultures—two vastly different ages. I am literally witnessing the adoption, or rejection, of contemporary ideas, products, and values from the west and east, as Tanzanians choose how much of their traditional identity to keep and how much to change.

|

|

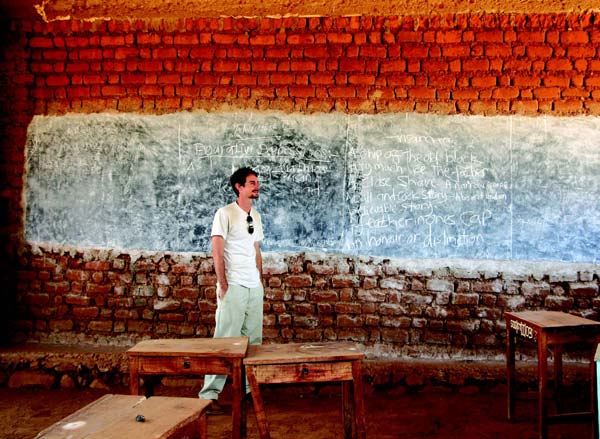

My job here is to assist this process as best I can, albeit gently, in order to not infringe on any major cultural boundaries. Although most of the daily challenges I face fall well out of my job description, there are small areas where I can make a productive difference. I’ve taught English, science and HIV/AIDS prevention at the local secondary school. I’m in the process of collecting donations to expand the small local clinic and to drill a well, which would provide year-round, high-quality water to the villagers for the first time. I’ve taken farmers on technical exchanges to learn new agricultural techniques to improve crop yield and reduce water usage. The response from the villagers has been enthusiastic, which justifies the investment of American tax-dollars for my presence here.

It is in personal exchanges, discussions and time spent together, where I truly feel my presence makes a difference, though. I have been blessed with many friends in my life, but never before have I appreciated the value of these personal relationships as I do here. Neighbors literally sustain each other through hard times. Even me, a “rich westerner,” can go to any house in the village and be fed any day. There is a care for life here; a strong cultural tradition that those who can feed the hungry, or help the needy, will do so. People care about and rely on other people. Family and tribal affiliations create strong bonds. This is how they have survived for generations, and this is what I will bring back to America with me.

As I watch this transformation, I am reminded of my own struggle for self-identification. I have learned from the people of Tanzania that these challenges are not problems in the sense that they require fixing, they are merely the substance of existence from which we fashion our experience; they are the occurrences which provide me the opportunity to choose who I am at that moment. Where I came to teach, I have been taught. Where I came to solve others’ issues, I am learning to solve my own. I am choosing how much of my past to bring with me into the future, and what the new values and practices are which I wish to incorporate into my current being. For me, life is now about self-creation rather than self-discovery.

This article represents the personal views of Randy Fish, not necessarily those of the U.S. Peace Corps.

|

|

RANDY FISH

Randy Fish’s Peace Corps Experience

Sometimes, getting words down on paper is like watching a hummingbird as it flits from flower to flower, trying to find nectar. As soon as one thought appears, another pops up beside it, turning your mind in directions that you never expected. Or, it’s like driving along a twisted road that you’ve never before traveled—while you expect each turn that meets you head-on, you’re never quite sure of your ultimate destination.

So it is with this story. It began simple enough; my wife Peggy and I were enjoying some casual conversation over lunch with friends, Bob and Jennifer Fish. As we discussed our families, they told us about their son, Randy, who is working as a Peace Corps volunteer in Tanzania. The more we heard about Randy’s work, the more intrigued we became. The idea of running a story in ALIVE was broached, and the direction seemed clear enough; we would do an article about how a local resident, Randy Fish, was helping people in a small Tanzanian village.

On the surface, one would expect the story of how a comparatively wealthy, educated westerner was working to “improve” conditions for people living in an impoverished, technologically backward village in Africa. But, as you will discover by reading Randy’s own words, the story of his work in Tanzania is deeper and more complex than one would assume. More than a story of service, it is a story of comparative values; of bridging cultures and seeking the common ground of compassion in cases where that bridge stands incomplete. More than anything else it is a story of self-discovery, understanding and empathy.

Snapshot of the Peace Corps

You remember the Peace Corps. They used to advertise fairly regularly on television during the 1960s and 70s. Until hearing Bob and Jennifer share their story about Randy’s experience, I would have to say that my image of the Peace Corps was pretty much formed through recollections of those old TV commercials—an image born alongside memories of the Vietnam War and the protests against it. Cast against the stark contrasts of that era, I suppose I envisioned the Peace Corps as just another government program, a feel-good enterprise, perhaps, being offered up to the world as a way for the United States to be recognized as a “good” nation.

While the Peace Corps is an agency of the United States government, my understanding of its purpose and value, has been what could best be described as superficial. And while I still retain a healthy skepticism when it comes to the real worth of just about every agency of our government, as I have come to know the story of Randy’s experience, I have gained an appreciation of this organization and how it functions that is different from what I assumed.

The idea behind the Peace Corps was first proposed in a somewhat impromptu speech delivered on October 14, 1960, by then Senator John F. Kennedy, to students at the University of Michigan. Perhaps as a warm-up to his famous “Ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your country” inaugural, Kennedy challenged the students to serve their country for the cause of peace, by volunteering to work and live in developing countries.

The students were enthusiastic about the idea, and on March 1, 1961, President Kennedy signed an executive order creating the Peace Corps as an agency of the United States government. By 1966, there were 15,000 individuals serving, and since then, more than 195,000 Peace Corps Volunteers have served in 139 countries throughout the world.

Currently, 7,876 volunteers are working at 70 different assignment posts in 76 countries. They work in myriad ways, applying their skills to a broad spectrum of needs. Volunteers are involved with farmers and small business owners, helping them develop ways to be more productive; they serve as teachers to both children and adults, and they aid entire communities in countless ways. Service in the Peace Corps is a commitment of 27 months.

Randy’s Life in Tanzania

After reading Randy’s first hand account of his experience as a Peace Corps volunteer in Tanzania, I wanted to know a few more details for our article. Randy’s father, Bob Fish, arranged for me to call Randy at 10:00 A.M. While there is no electricity or land-line telephone service in the village of Dawar, Randy does have cell phone access powered by a solar charger. With the time difference being ten hours, making it 8:00 P.M. Tanzania time, it was a fairly convenient time to call.

I asked Randy to elaborate about his mission as a Peace Corps volunteer. Certainly, he went to Dawar with the expectation of helping people improve their lives. In that context, I asked Randy to tell me about how the people of Dawar are reacting to his efforts there. One big question I had was, why is it that a group of people, who have existed for what is possibly thousands of years, remain so technologically behind the rest of the world? Why does poverty and their primitive lifestyle persist, despite the efforts of so many outsiders who have tried to help?

Randy: When I first came here, that was the idea. I’m coming to make things better—to help people and to change things. But what I found was things are changing but they are changing at their speed. They are deciding what to change.

I’ve learned that there is no ‘better’ really, there is only a ‘different’ way. Some ways produce more than others. Some ways, you do get a lot more corn for example, but it also takes a lot more time—which is less time to spend with your family. It’s less security because you might have to invest a lot of money to buy seed, let’s say, and then, if a drought comes, it’s much less of a benefit. You spent all that capital that normally you wouldn’t spend, and you get no return. So, instead of that, they would rather spend very little capital and get a smaller return than take a big risk and not know about the return.

It’s a very ‘Tanzanian’ trait-not to assume risk.

There is very little security in day to day life here, so any time you give up a little bit of that security and try to get a reward later, that’s a very shaky proposition.

EJ: Is corruption involved here that helps create the technological disadvantages suffered?

Randy: Corruption is very bad here. For example, you could invest a lot of money to send your kids to school, but the teachers don’t show up. People are very disenchanted with the institutions in place. Institutions that have, in the past asked them to invest and take risks, in the past those institutions have let them down. The risks they’ve taken didn’t bring the profits promised, so there is a lot of distrust now in promises, especially from outside influences.

EJ: So, it’s more outside forces involved that hold the people back?

Randy: Corruption is very much within the village itself. For example, there are really three smaller villages within a larger village. They decide to assess a tax of ten dollars per family to finance a water system, but then you have a corrupt tax collector and the money disappears. I pick who I work with very carefully, especially with money. And often, it’s even your neighbor or even your best friend that will steal from you.

EJ: So how do you deal with that? How do you help these people?

Randy: My goal is to help those who want to change—to help those who want to help themselves. I’m not an agent of change, I am a motivator of other agents of change.

One thing I really want to stress is that when we first come here, we have this idea that there is this thing called a ‘community’ and that we are going to go and help the community. But that’s very much a fallacy. It’s individuals that we end up touching and who end up touching us. And it’s the same, I would venture to say, for every Peace Corps volunteer. You get on a very individual basis—it’s personal relationships that it’s about.

EJ: What, if anything, surprised you most, about living and working in Dawar?

Randy: One thing that surprised me—the biggest difference—is just the closeness of families here. Families and neighbors. They have a saying here, “It’s better that a far away family member dies than a neighbor.” Because you are very close to those around you. Communities are so interconnected—so many inter-personal relation-

ships, and they rely on each other so much. Time has shown them they can’t rely on the government or on outside influences. People rely on each other.

Social relationships are very strong here. For example, if you’re visiting, it’s considered rude if you’re not offered food. In the U.S., if someone comes to your door at dinner time, people say, “Come back later. We’re eating.” Here, it’s, “Stay. Eat.” Food is one thing most families have and they share it.

EJ: Do you miss home and your family? Things like being able to jump in your car whenever you want to go somewhere, and electricity and running water and being able to take a shower?

Randy: I don’t really miss it, but I’d have to say that I have a greater appreciation for the time when I do get to be with family. I love it here. I love the peace and quiet. I love the stars. I love that you don’t know if you’re going to be able to shower tomorrow; if water’s going to be available. There is something nice about being unsure of

what’s going to come. My desire is not to return to America, my real desire is not to forget—not to forget what we’re really doing here.

EJ: What would you tell school kids back in the States? What would you say about your experience and would you recommend it?

Randy: I’d say there are all types of education. A very important one is in the classroom. But you can’t forget to go outside. You can’t forget to learn from yourself and that you can be your own teacher, or that there are other teachers outside of school. I’d say, learn as much as you can and experience as much as you can. Just live your dreams.

How to Help

EJ: What, if anything, can ALIVE readers do to help you in your efforts?

Randy: The maternity ward is the big project that I’m trying to help this community—my village—build. I’ve written a Peace Corps partnership grant proposal which allows private donors from the States to contribute money through a Peace Corps fund that will go directly to this community and this project. There will be a link on the

Peace Corps website to donate to this maternity ward in my village.

Information about the Peace Corps can be found at their website at www.peacecorp.gov or at their toll-free recruitment number 800.424.8580.

ERIC JOHNSON

Message From Moscow

Bart Dorsa, a lifelong resident of San Jose, has lived in Moscow for six years and has achieved more in that short span of time, than most young transplanted Californians could ever hope to expect. We had emailed back and forth between Moscow and Danville to set a time for a phone interview which finally materialized when he was driving from Los Angeles to San Jose for a local event.

I had followed Bart’s interesting life in Moscow through his parents Marilyn and Frank Dorsa of San Jose, and since I’ve known him since he was four years old, I took a special interest in his life and successes abroad. I had made a list of twenty burning questions about his career in Moscow to get the article going. I should not have been surprised at the titillating answer to question number one, and I saw that the interview had taken on a life of its own.

“Well Bart, tell me about the interesting women in Moscow. Is there anyone special?” I asked.

“Did you know I was engaged to twins?” was his first question to me.

“Yes Bart, I had heard that but I thought it was a great comedic throw-away line,” I answered.

“Well, it was great while it lasted—the twins Nadia and Luba were singers in their own band and they had been dating men who were jealous of their close sibling relationship so they both decided to marry one guy. We all three got engaged. I was the lucky guy,” he laughed.

I went on to my next question about his work in Russia. It was fascinating so far, to say the least. Once Bart had settled in Moscow, it lead to his liaison as a managing partner with one of Russia’s most creative emerging fashion designers, Vika Gazinskaya, who has since found her creative niche in the competitive world of design in the Eastern Bloc countries as well as Paris.

Bart Dorsa took control of the business, public relations and production end of the seasonal fashion show extravaganzas that were soon featured in top European magazines. Even though the fashion show production end of the business was extensive, he continued shooting an artistic-genre of photography which led to exhibits of his art at local Moscow venues. His creative work was noticed, and he garnered critical reviews.

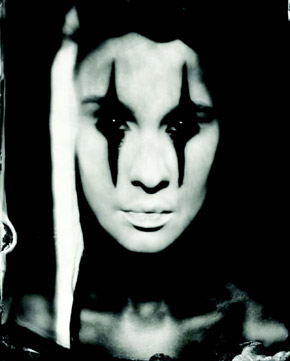

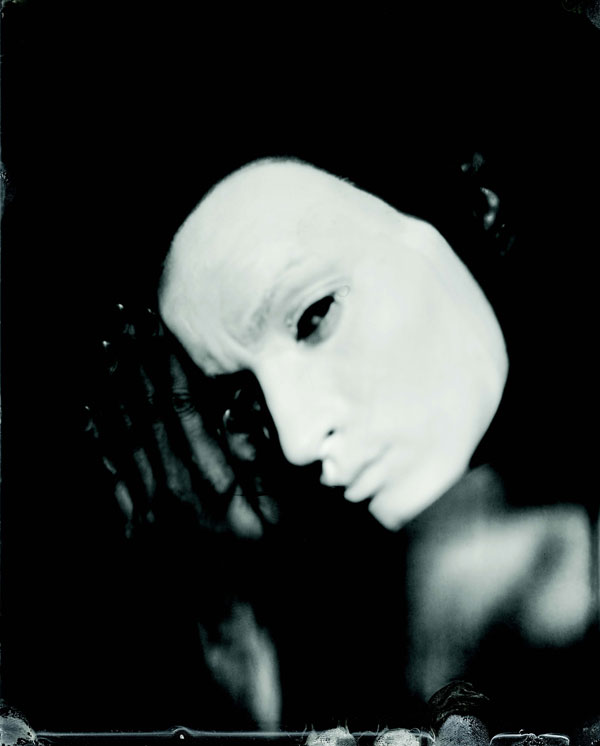

He soon ventured into a field of a new kind of photography by using an old technology with an antique tripod-mounted 19th century wooden camera. The ghostly faces in his photographs, as if the subject is peering out from the past, drew positive critiques of a most unusual old-fashioned concept that had crossed over to an albeit contemporary art form. Bart Dorsa has captured ephemeral photographic images that are hauntingly captivating with a lingering sense of the long ago past.

This highly unusual art form in the field of contemporary photography, with the use of an earlier technology, led to further recognition of Bart Dorsa as a creative artist-photographer. It was just a matter of time, after so much acclaim about the artistically surreal art form, that top Moscow models and others sought him for his unusual camera work. Dorsa shot each subject with the idea that his artistic guidance of light would allow the antique camera itself to interpret the photograph. The photographs, which are manipulated by patient developing techniques, emerge as quasi-intangible, diaphanous, ghostlike images. The photograph is captured by the fast opening of the shutter for a few seconds—a fraction of a moment trapped in time—which is already in the past within seconds, with an image that could endure for ages.

Bart Dorsa conceptualized that a total immersion in the visual art form was integral to the ethos of his photographs. It was a no-charge, no-pay venture and some of the eeriest images of Moscow’s beautiful women, and those not necessarily photogenic, were artistically captured this way as if they reach to the present from the century past. The results are eerily unearthly, to say the least, but bear a fleeting gossamer grotesque beauty that cannot be achieved with textual mainstream photographic techniques.

When I asked Bart if the Russian women are more sophisticated at an earlier age than their American counterparts, he answered, “The Russian women develop a classical femininity at an early age which is then very restricted. They are beautiful and sophisticated in their look, but are still very young.”

I asked him to describe his daily routine in Moscow and he told me that he is working eight to twelve hours a day in preparation for his one-man photography show at the museum. “I try to get at least six hours of sleep every night. The people work hard in Moscow and hard work is expected. The summers are humid and uncomfortable and the winters are bitterly cold – freezing bitter cold. The Russians work hard and they play hard. And the most noticeable difference about the Russians from the Americans is their excitement about simple everyday things—they are passionate about everything and do not have the chronic cool detachment we see in America. They get intensely excited about the little things and enjoy every aspect of life to the fullest.”

“Speaking of bitterly cold weather, Bart, how do they feel about global warming? Is it an issue? Is it ever discussed? Should I dare even ask,” I enquired.

“They’re celebrating global warming! It’s so cold over there; they love to hear about the normal cyclic warming. It’s nature at its best.” We laughed.

“Are the Russians outwardly concerned about their political climate?” I thought I already knew the answer to the question, but I asked anyway.

“Moscow is a city of twenty million people and they gently accept what’s going on. They’re not impassioned about their politicians; there’s not much they can do to change anything, and the Russians are famous for their stoicism. They go about each day, stoic in their beliefs, and they live hard lives in dangerous cities. Besides, I don’t get into talking much about Russian politics. Life is hard in Moscow, as elsewhere. Many people have lost their investments and their jobs. There are big pay cuts and there is daily hardship, but the people continue to live their lives and go to work every day. Their tradition of stoicism is that life goes on.”

Bart Dorsa has a different outlook on life and his work in Moscow now. He is more impassioned than when he was producing and directing films in Los Angeles. His film The Invisible made an appearance at the coveted Robert Redford Sundance Film Festival and the once-dormant Here Lies Lonely is soon to be released. The production end of his film work was what gave him the artistic impetus to work in still-photography in Moscow. After his rapid success in that field he gradually moved away from the medium as a digital camera photographer and artistically ‘regressed’ to the photographic technology of the past that was first introduced in 1839.

Bart is now working mostly with the antique mid-19th century collodian or ‘wet-plate’ camera. “I can work in the middle of nowhere and I don’t need to depend on anything from the outside to complete my project. It makes me fiercely self-reliant and independent.”

I always knew that about Bart.

I always knew that about Bart.

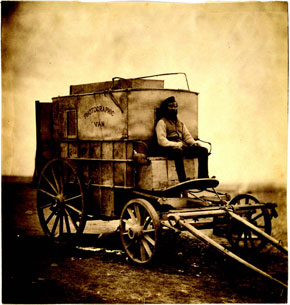

The antique camera offers difficult challenges and a special expertise of infinite patience. The camera is large, heavy and bulky and is housed in a wooden box on a pedestal with a black cloth to block the light while the photographer shoots the photo. Bellows move the lens forward to the subject, the glass plate is placed in a slot and the image is exposed on the glass and within seconds it needs to be developed from a negative to a positive. That is how the very first facsimile images were captured on glass or on tin plates one hundred and seventy years ago. This process required developing-chemicals such as the syrupy solution of pyroxylin in ether or alcohol and other complicated flammable mixtures that were very different and much more dangerous than today.

The collodion process, introduced in 1851, takes a slow and accurate technique. It requires a special patience and a step-by-step process, far beyond the f-stop photography that preceded today’s digital cameras that have made the art of photography somewhat boringly instantaneous.

“The antique camera gives me more artistic control and I can do all my own developing by creating my own formulae with emulsions of collodion, cyanide, ether and other chemicals. I create my own chemistry to make the photographs on glass. None of the developing processes need any dependence on outside sources. It is an independent and resourceful procedure. No single regular commercial product is needed to create the photographic art. It is a process that I work on from the making of the image by exposure on glass to the final end product,” Bart Dorsa explained.

“People face failure everyday and we are always in a creative crisis—meeting the challenge and succeeding is an irreplaceable reward. My work takes me away from the chaos of life. It is very rewarding, even though my hands and feet are black from the silver used in the process.”

Photography has recorded our lives for seventeen decades, not long in the grand scheme of visual art, by any means. The dawn of photography emerged almost simultaneously in 1839 when several scientists were able to create a method of fixing an image by allowing light to be transmitted through a camera lens that left a mark on paper or sensitized glass plates. The camera oscura—Italian for dark room—evolved to fruition by the incremental expertise of Nicephone Niepce, Louis-Jacques-Mende Daguerre and William Henry Fox Talbot who together set the technology in non-stop motion.

A few years later Frederick Scott Archer invented the first practical wet-plate photographic process to be reproducible when he coated a glass plate with a collodion solution and

exposed the plate while still wet. Voila! By 1880 George Eastman perfected the dry-plate process, and the Eastman-Kodak Company has since clicked its way into photographic

history cornering the world’s market share of photographic papers and film.

Photography developed, since 1839, from the primitive technology of the tripod-mounted wooden camera with a bellows and black hood, to the box Brownie, the f-stop wonder Rolliflex camera and to the recent palm-sized models that give us the instantaneous results.

My curiosity, about the almost-extinct cameras, led me to ask Bart what had inspired him to pursue the cumbersome technique-driven and archaic 19th century methods of making primitive photographs with such a time-consuming and patience-taxing set of challenges.

“Bart, why did you revert to the old-time cameras? Is it not more difficult to work with such archaic technology? What inspired you to make your photographs with old cameras?” His

answer was actually quite surprising to me.

“I saw the haunting images of Lincoln and a man named Powell at the National Archives in Washington D.C. and became mesmerized,” he answered.

The avant-garde, yet ethereal classic style of photography that Bart Dorsa has created with definitive modern nuances, and with the use of an archaic mid-19th century camera has

received the coveted attention of the curators of modern photography at the Moscow Museum of Modern Art—the MMOMA. The MMOMA has a substantial permanent collection of 20th century artists such as Pablo Picasso, Fernand Leger, Joan Miro, Marc Chagall and Kandinsky that are exhibited at their main museum in addition to their other three venues in the historic quarter of Moscow.

|

|

Bart Dorsa, an American artist, has been given the honor of having his innovative photography exhibited in a one-man show at the esteemed MMOMA, and his 120 piece iconic photograph collection will be installed near the year’s end by the museum with special lighting effects at one of the historic museum buildings.

Bart Dorsa has defined the essence of photography from the 19th to the 21st century by taking a fresh innovative artistic approach, much like prior exhibitions, Soul Stealer and Silver Tongued Devil. His pioneering work has taken him on a quintessential photographic journey of one-of-a-kind haunting images with eyes of clarity that search from the distant past to the bright light of the present – their ghostly souls captured maybe for forever in a brief ethereal moment of time.

THE PHOTOGRAPH: A MOMENT IN TIME

It is true that early images of people and those photographed during the American Civil War have an eerie haunting quality to them. The faces are devoid of expression and there was never a smile when the sitters looked into the foreboding camera. No doubt it was their first time facing a wood box which was purported to capture their very images. The exposure—lens aperture for light—took a long time and the subject had to sit unsmiling and very still for a few minutes so the image would not blur by the long exposure time. The period of immobility is what led to blank stares along with the trepidation that the photographs were to be carried far away by family and perhaps were never to be seen again.

It would remain the only remembrance of their image.

During the Civil War, soldiers were specifically photographed in the battlefields as a tangible reminder that they were proudly fighting a war and their images would serve as souvenirs. Very few people could afford a photograph as the cost was equal to a week’s pay. Traveling photographers made daguerreotypes of soldiers who may very well be dead before the images were developed in the horse-drawn ‘dark room wagon.’

It was not the first war to be recorded with photographic images; Roger Fenton was the earliest traveling photographer sent on assignment to the battlefield in the1853-1856 Crimean War. He bought a horse-drawn wagon from a London wine merchant and rigged it as a mobile dark room van and shipped it on the Hecla, a troop ship that sailed to the Crimea in the Black Sea. Fenton was the first photojournalist to ever be embedded with troops on the battlefield for three months in 1855.

Fenton produced 360 photographs in the Crimea during his three-month stay, an enormous achievement for an on-location war zone, camera set up and instant developing. His assignment was to omit images of misery and tragedy and capture only patriotic images of generals and COs in battle dress to appear victorious for the front pages of London’s newspapers. It was to be the first recorded photography used as visual propaganda for the British war effort in the conflict against Imperial Russia with the French, Turks and Sardinians as allies. The Crimea was the location of the iconic Charge of the Light Brigade where over six hundred British and Irish men charged into the wrong valley and into the cannon fire of twenty thousand waiting Russians.

Roger Fenton moved on to Moscow after the war to photograph the city’s spectacular architecture, but will always be remembered for his haunting images of battle-dressed British generals, French Zoaves, and conical field tents spread across windswept Crimean battlefields.

The realities of war, through Fenton’s photographs, lead to a widespread negative reaction by the British public and many of the historic photographs were liquidated at auction. In 1944 the U.S. Library of Congress purchased 263 of Roger Fenton’s photographs from his grand niece and the historical collection can be viewed in their online archives: LibraryofCongress.org.

Photographs copyright Bart Dorsa

ANITA VENEZIA

November 2009 Cover