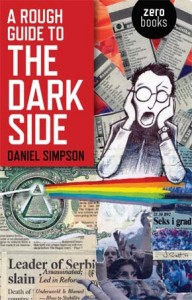

I interviewed Daniel Simpson at Danville’s READ Booksellers, promoting his memoir, A Rough Guide to the Dark Side. Had I not sat down with the author and heard his story first-hand, I may have imagined his memoir was fantasy. It was not.

I interviewed Daniel Simpson at Danville’s READ Booksellers, promoting his memoir, A Rough Guide to the Dark Side. Had I not sat down with the author and heard his story first-hand, I may have imagined his memoir was fantasy. It was not.

As an ex-New York Times foreign correspondent, he is shrewdly well-seasoned and knows how to hit a nerve. The memoir is a journey to the dark side of reporting—and tweaking stories to fit NYT paradigms of Iraq war-time sensationalism, and smorgasbords of drugs.

The book’s theme is an acutely biting and critical indictment of modern media practices, and how Simpson got mixed up with Serbian underworld thugs. His adroit use of language, peppered with politics, moves through a mazelike exposé of journalistic practices that he deems to be, not only untrue at times, but often having objectives to purposely mislead. He states, in keeping with media convention, some facts are more factual than others, contending that the NYT is a blatant propaganda megaphone.

Daniel Simpson, 37, is an English Cambridge-educated historian. He cut his journalistic teeth at Reuters as financial correspondent in Frankfurt, and then war-torn Macedonia. In 2001 he covered Romania after regime change when Stalinist dictator Nicolai Ceausescu and his wife were assassinated in 1989. He interviewed the assassins whose act had put Ion Iliescu in power, but the executioners got no glory.

NYT noticed Simpson’s Reuters reporting and hired him for the Belgrade bureau to cover political turmoil after Yugoslavia disintegrated. Most Balkan war correspondents had been dispatched to Afghanistan after 9/11.

Simpson was twenty seven; admits to being enormously naïve about NYT expectations, and the post-war Serbian mood. Former Yugoslavia was an ethnic mosaic; many murdered for their beliefs and some Serbian war criminals already at the Hague tribunals.

News about WMDs and terrorism was leaking from many sources after 9/11; the U.S was preparing to invade Iraq. NYT asked Simpson to hype some “news” about Yugoslavia defense companies developing cruise missiles for Iraq. He writes “news came from the Belgrade U.S. embassy; robo-diplomats claimed to have some documenting evidence.” Foreign deskers “wanted stories ‘faked’ to align with the president’s plans.” Editors tweaked his filed reports. The Washington Post had already run with the story. Simpson states he wasn’t big on faked sensation; so he went AWOL on ecstasy.

At the onset of his journalism career, Simpson had had fantasies of adrenalin-inducing excitement, being a front-line correspondent, dodging bullets, scooping stories. The Balkans beat did not offer near-death experiences, albeit Serbia was in post-war turmoil. NYT, publisher of all the news fit to print, wasn’t challenging enough for Simpson; the idealist longed to change things, wanted to revolutionize Serbian youth with music.

“I really thought I could change the world,” he said wryly.

So, with a solid dose of cannabis-fuelled idealism, Simpson partnered with G, a gregarious Serbian concert promoter. The duo burst onto culture-starved post-Milosevic Belgrade to spearhead the 2003 ECHO music festival on the heels of the EXIT extravaganza held each summer in a northern provincial town.

His vision of promoting such an event did not include the doom factor, due diligence, or that he was navigating into the dangerous Serbian mafia underworld.

Distracted by festival planning, and disgusted with the NYT demands to sensationalize stories—Simpson quit. He had bigger fish to fry. So, in true gonzo journalistic style, he put himself in the middle of the action, the neophyte rock-star wannabe starred in his own story. But the protagonist was about to get ripped off.

DARK SIDE GETS DARKER

Although Daniel Simpson quit the New York Times a decade ago, he unabashedly references his former gig to promote his memoir, A Rough Guide to the Dark Side. “It opens doors for me. When someone hears I am an ex-New York Times reporter it adds clout. They all want an interview,” Simpson smiled.

Ten years ago, the then-27-year old journalist had reached a crossroad; the festival was a “transition mechanism” of magnanimous proportions. Sans street-cred or connections, except for G, he chucked journalism to produce the music festival. The man who earned a living asking questions, asked himself the sublime question—why? The answer to the esoteric question revealed he wanted to change things—he yearned to make a difference, bring the Balkans’ fractured factions together with music. He confesses he was heavily into drugs, and dealing.

Daniel Simpson’s avant-garde memoir, A Rough Guide to the Dark Side, reveals his journey; Kerouac’s On the Road comes to mind. Chapter titles reveal the mood; ZERO, LUST, HERESY and REVELATION, as does author’s note; “I hope this isn’t fiction, or one-sided…”

Simpson, with journalistic page-turner brilliance, starts with the killer first line, “I never really meant to join the underworld. I fell in.” He expected to connect with the youth, alter conflict-scarred Serbia by staging ECHO, a summer-of-love Rock Music Festival on Belgrade’s Big War Island in the Danube. He envisioned eclipsing the EXIT festival, a musical marathon-cum-political-protest that boasted 300,000.

Simpson’s memoir reads like fiction, but it’s not. Hooking with politically-connected street-savvy Serbian partners, the ECHO event emerged as Burning Man meets Woodstock.

Politicians and money-men met with Simpson on the strength of his NYT connection; it gave him clout. He knew the U.S. funneled funds to the Otpor youth group to mount resistance to oust Milosevic; some from three-letter U.S. agencies. EXIT had secured 200K. So Simpson, imbued with anti-establishment idealism, and armed by a drug-fuelled ignition switch, secured funding for the project. Drunk with resolve to make a fortune, and unbounded naïveté about the Serbian culture, he and partners succeeded in pulling off the ECHO Music Festival; albeit at great personal cost.

He conceptualized that ECHO would be the magnet to rally dissidents against political corruption, police brutality and decades of discontent, not permitted during Slobodan Milosevic’s regime. Simpson orchestrated ECHO unaware he was treading on dangerous territory; gangsters waited in the wings.

Simpson, still a NYT correspondent during festival planning, filed regularly. When Prime Minister Zoran Djindjic was shot in broad daylight near Simpson’s flat, the Times wanted a sensational front page story. Bullets had shredded him; some thought the hit came from the Zemun underworld. Simpson had to work fast to file for the front page. He had a lot of distractions.

“I was lost in listening to hip-hop music, visions of how everything could be explained…I trusted G, not knowing if he would hoodwink me, he was a gambler man, fearless, charismatic…maybe he knew ECHO would be doomed. I didn’t want to just do a couple of DJ nights—I wanted a full blown Woodstock.”

He had to file the Prime Minister’s assassination quickly. Instead of doing “man on the street” interviews, Simpson asked his translator and her friends what they thought. He settled for ‘rent-a-quote’ opinions, and extrapolated from news wire cheat-sheets. He faked interviews with fake diplomats. “I can’t defend that ethically.” His memoir answers many questions, and tells why he made up stories for the New York Times.

The production of ECHO festival on Big War Island in the middle of the Danube was a logistical nightmare in post-war Serbia. Paramilitary security contractors with guard dogs were hired to protect money-takers and ticket-holders. Scuba divers searched the river for bombs. Simpson was peddling class-A drugs at the festival, an offense that could entail jail time. But precautionary measures did not prevent what was yet to go down with the Serbian mafia.

Over 150,000 attendees showed up for the 4-day raver; 100 acts and 300 artists on four stages. The Serbian army had erected a 600-meter pontoon bridge from Zemun to Big War Island in the middle of the Danube. Four circus elephants ridden by Russian acrobats lumbered across the bridge on opening day. Visitors from several nations flocked to the love-in at 25 Euros apiece. Cash rolled in. All went well until torrential rains knocked Sonic Youth out of the line-up on the last day. It was an island of mud. The storm was a harbinger of what was to come.

Simpson’s grandiose dreams were dashed—all the money was stolen. The catastrophic finale of the big cash rip off proved that maybe politicians and partners were in cahoots with the Serbian mafia. Simpson is not sure what role G played in the scenario, and what went down with the gangsters.

Simpson admits to naiveté about encroaching on mafia domain. Manic idealism, high achievement tendencies and continual stonedness convinced him that techno, funk, salsa and soul music of Sonic Youth and Burning Spear could bring unity to disintegrated former Yugoslavia. He confesses to having cynical jadedness as first, describing the Belgrade war zone as “a miserable pariah”. But when he met G, nothing seemed impossible—charisma overtook judgment. Maybe things got lost in translation; G called American money the ‘one-eyed pyramid’. “Music had revolutionary potential…” In retrospect; perfect for ‘washing cash’.

He saw more than revolutionary potential; a blockbuster would generate cash while bringing splintered factions of the Balkans together. So Daniel Simpson, sporting a new Serbian soubriquet, Raoul Djukanovic, interviewed himself, generated a buzz, clinched funding and pitched the ECHO deal dreaming magnanimous dreams. Drugs were big in Belgrade, and being “mentally jellified”; the nightmare was yet to follow.

DESTINATION: OBLIVION

The festival had ample sex, drugs and rock ‘n’ roll, but with the lack of due diligence of Serbian culture—ECHO failed. The promoters filed bankruptcy; police and printers threatened, performers’ expenses went unpaid. Some accused Simpson of being a British spy. His change-making dreams crumbled. Serbian underworld gangsters had struck a coup de grace with a vengeance.

Simpson said booking the bands was tough; “names bring faces…” Disappointing everyone was a fiasco, no one got paid. Maybe scalpers printed tickets; maybe security and partners were in on a scam. There was a lot of cash—who knows how it disappeared?

So ECHO did not end well for the ex-New York Times foreign correspondent, now seeking answers, trying to find himself. “I wrote A Rough Guide to the Dark Side as a catharsis; to be kind to myself…I wanted to be a better journalist. I needed to look inside myself, in reality I was lonely, I had anxiety and depression, I quit my job, lost a fancy title, took risks, had to look inside me, had to learn how to love others and myself. I searched for the meaning of life on a rollercoaster adventure.”

Simpson admits he may not have had the clout to produce ECHO had he not been with the New York Times, confessing to mild deceit. “I wanted to say something, do something; be someone.”

I was more interested in Daniel Simpson the journalist, than Daniel Simpson the concert-promoting drug-dealing addict. I told him that drugs did not define him, his brilliance as a writer is what defines him. At first I said I would not mention much about the drugs, or that he was a stoner, but I would be dishonest not to. The crux of his memoir hinges on drugs; it is the tour de force of his past.

I read A Rough Guide to the Dark Side and numerous NYT articles. Daniel is bright, has swift wit and a quick smile. The high-achiever is hard on himself, demands perfection, cuts himself no slack. He is very likable and laughs a lot. “I have not used drugs for four years,” he says, “I practice yoga; it has been a way of life since long before organized religion. I write about yoga.”

My final question was a surprise. My quest was to penetrate the masquerade; I needed more backstory on my interviewee. “Daniel, if you were to interview yourself, what would be your first question?”

Daniel Simpson’s answer was long; I would have to paraphrase and condense. His forthrightness surprised me. He frankly flaunts his failings, maybe to shock, maybe to be honest. A Rough Guide to the Dark Side tells his life in gripping staccato style. His dark side chronicles hallucinatory time passages through a hip-hop culture—evoked to sanction the retreat from himself and his outrageous actions.

I asked Daniel Simpson about his grueling book tour at Blackhawk’s READ, and wished him Godspeed. “I launched A Rough Guide to the Dark Side in London. I’m traveling by Greyhound across the United States, with stops in New York, Texas, North Carolina, California, Oregon, Washington, back to London, and then to India to be with my girlfriend.”

www.roughguidedarkside.com,at READ Booksellers, Danville and Amazon.