Regardless of where one stands on the removal of Confederate statues and monuments I’m sure everyone would agree that the recent, ultimately tragic events in Charlottesville, Virginia, got very far out of hand.

A few legitimate, important questions that ought to be answered are, “Why did the Charlottesville city government issue permits to two opposing groups—groups with obvious hatred towards each other—for events on the same day, in the same area? And, considering the issuance of those permits, why then wasn’t there adequate preparation by law enforcement for what was sure to be a volatile situation?” It looks to me as though either the city officials in Charlottesville wanted a violent eruption, or they have as much combined intelligence and common sense as a bag of hammers.

Despite what appears to be the consensus of media and politicians’ opinions aligned against President Trump, I tend to agree with his assessment—that both sides are to blame for attacking each other. But even more than this, I blame the leadership of the Charlottesville city government and law enforcement for not acting sooner, in order to prevent the melee and its ensuing tragic loss of life.

With numerous rallies and events concerning similar, emotionally charged issues no doubt to come, it would be good to remember that oftentimes, physical laws can be appropriately applied to emotional situations and human relations. For example, in its best recognized form, Newton’s third law of motion states:

For every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction.

Or, as a more precise definition states it:

When one body exerts a force on a second body, the second body simultaneously exerts a force equal in magnitude and opposite in direction on the first body.

Obviously, this might be a good “law” for everyone to keep in mind when it comes to such inherently-volatile situations. Who’s right and who’s wrong are beside the point; if you push, it’s a near certainty that you’re going to get pushed back. Human nature (and Newton’s third law) has confirmed this to be true for eons.

The Future: Where do we go from Here?

It does little good to keep looking back, unless we are focused on what needs to be changed while moving forward. What approach shall we take in our efforts to affect societal change through freedom of speech and expression, that best eliminate the risk of cracked skulls and destroyed property? Fortunately, there some good examples offered in history, if we have the desire (and wisdom) to seek them out.

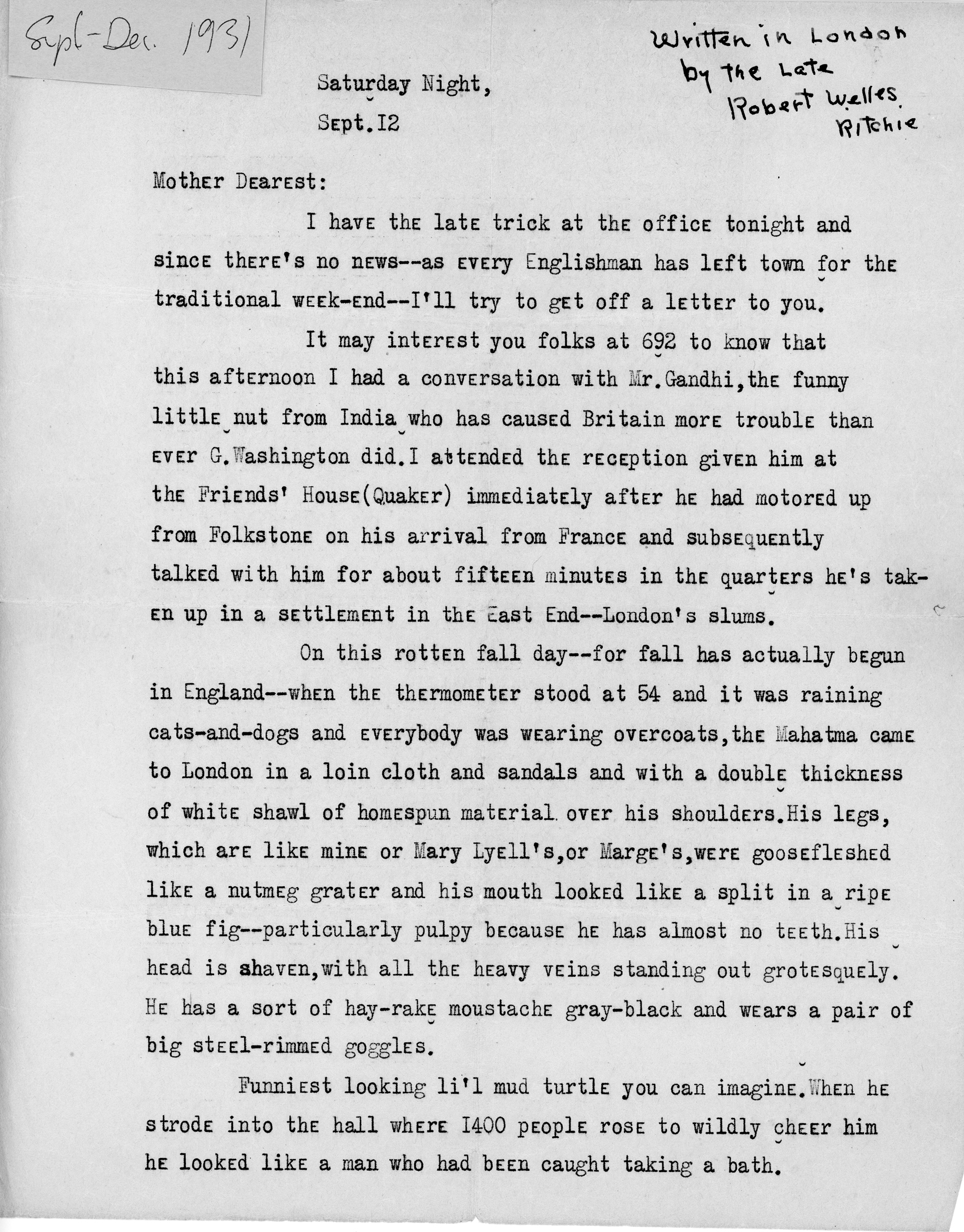

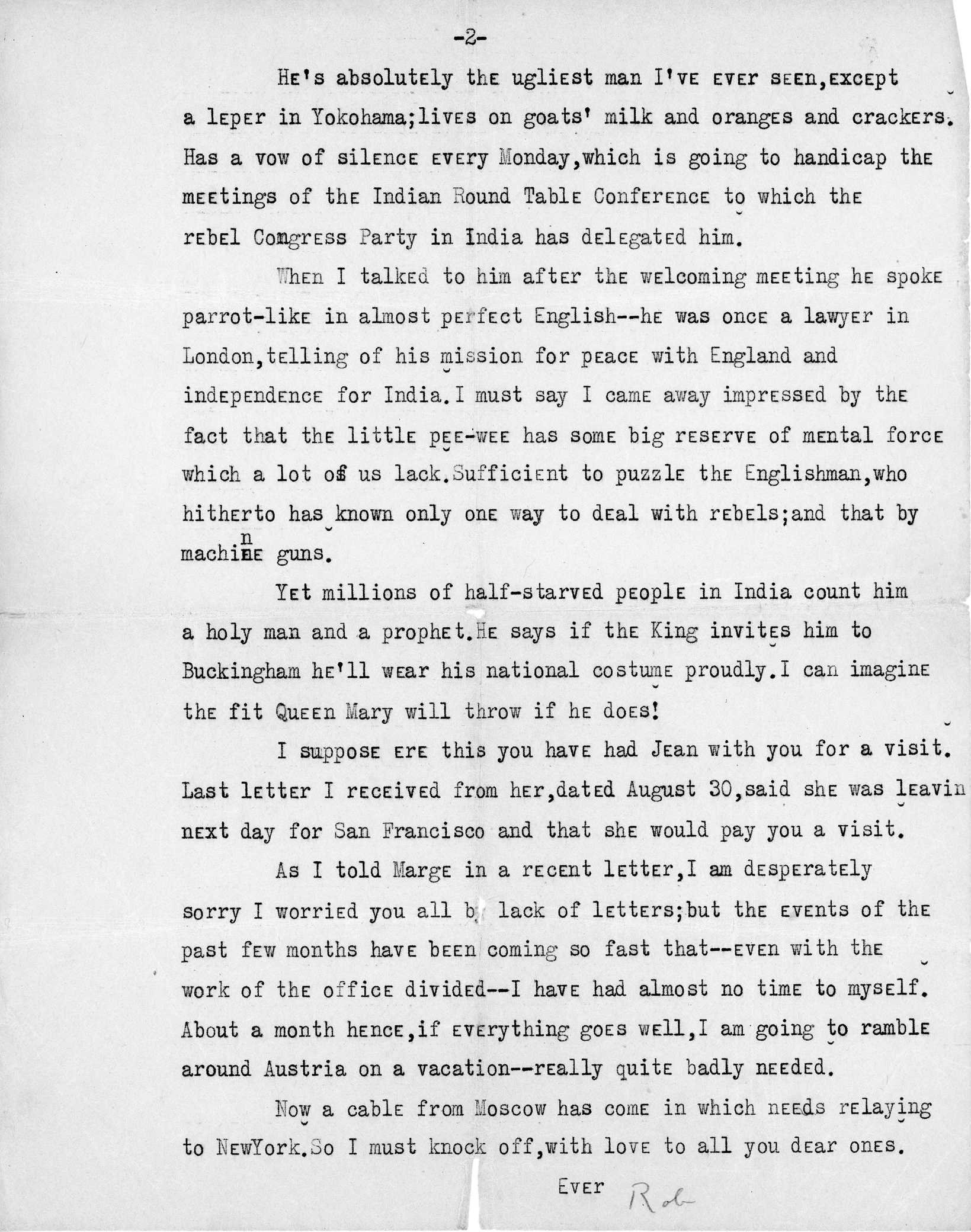

My brother-in-law recently came across an old family letter that might suggest one such example. Written by my wife’s great uncle, Robert Welles Ritchie, in 1931, it was a personal letter to his mother.

Robert Welles Ritchie was a prolific writer; a novelist, screenwriter for a number of black and white short films, as well as the author of numerous articles and short stories for publications like Harper’s Magazine. He was also a correspondent for the New York Post, in which capacity he met with and interviewed several notable people, such as Admiral Robert Peary, and Mahatma Gandhi. It was his meeting with Gandhi that was the subject of his letter to his mother.

Of course, Gandhi is considered by many to be a prime example—the epitome, perhaps—of a leader who championed non-violent tactics as means to affect meaningful change on a massive scale. He well knew the laws of physics—and human behavior—and used that knowledge to gain peace with England and independence for an entire nation.

In reading this rather brief letter, you not only get a sense of what Gandhi was like, but you can also see the impression he made upon Ritchie, as he described it:

When I talked with him after the welcoming meeting he spoke parrot-like in almost perfect English—he was once a lawyer in London, telling of his mission for peace with England and independence for India.I must say I came away impressed by the fact that the little pee-wee has some big reserve of mental focus which a lot of us lack. Sufficient to puzzle the Englishman, who hitherto has known only one way to deal with rebels; and that by machine guns.

I am by no means a pacifist. In times when hostility is certain or when self-defense or the defense of the innocent require it, the use of force—and yes, even war—is justifiable. But prior to that “no turning back” point, if we are wise, we will know that the laws of physics—of human nature—will overcome our better natures if we allow it, and then all we accomplish is further division and animosity.

By all means, protest; demonstrate, and voice your opinion… but allow others to exercise the same right, always taking into account Newton’s third law. You will never win others over—you will never change the minds and hearts of others—using brute force. All you get by pushing is more pushing—but now, in your direction, against you! Hit someone and they’ll likely hit back with even more force.

And trying to change one’s thinking by smashing a statue of Robert E. Lee will be about as effective as trying to change someone else’s mind by defacing a statue of Martin Luther King. This kind of “protest” might make one group feel good, but in terms of change, it only serves to move everyone backwards.(Again, in practical terms, “as smart as a bag of hammers” applies here too).

The best strategy to effect change is to truly win others over to your way of thinking—or at least get them to “agree to disagree” on civil terms, and Gandhi provides a good example as to how success is eventually best achieved.

Shown below is a copy of the letter written by Robert Welles Ritchie to his mother, September 12,1931, describing his meeting with Mahatma Gandhi in London.