After graduating from California State University, Chico in summer 2006, I didn’t have a clue what my passion was, what I wanted to do, or who I really was. The only thing I was sure of is that I was not ready to enter the ‘real world.’ So, instead of plunging into the depths of a 9 to 5 office job, I decided to join the Peace Corps. I was finally posted to Tanzania in June of 2008 as an environmental education volunteer.

In the two year interim, I attended graduate school at Michigan Technological University, and had plenty of time to formulate expectations for my Peace Corps experience. By seeing life from the eyes of those less fortunate than myself, hearing their stories, and living as they live, I reasoned I should be able to discover the original humanity within all of us, get a glimpse of my own in the process, and figure out what I want to do with my life. There was also the allure of the simple life in a mud-walled hut, surrounded by jungled wilderness, helping impoverished people alleviate some of their problems, and, of course, plenty of time to hone my yoga postures.

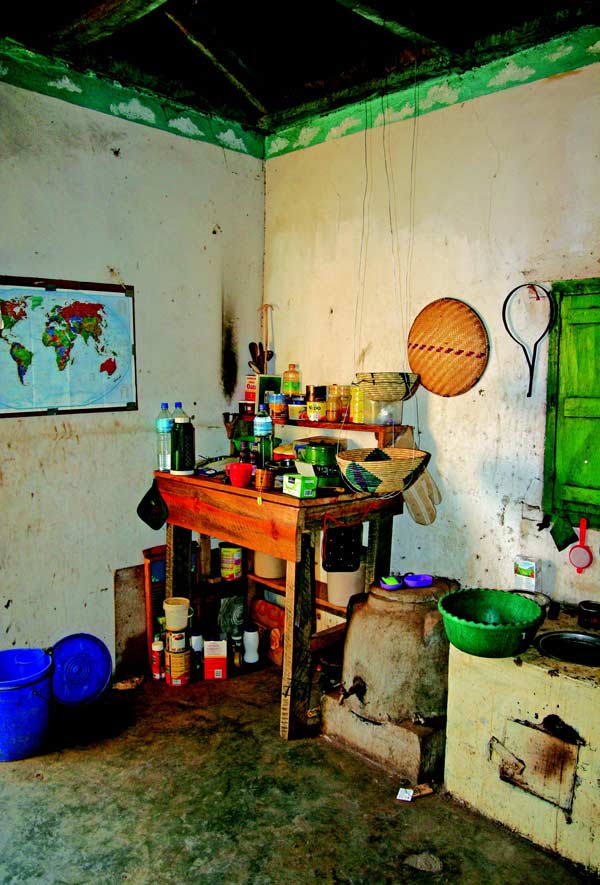

In August of last year, I unpacked my duffel bag at my tiny (300 sq ft) cement floor house in Dawar, a village that is not on any map. It’s located in the Great African Rift Valley, just south of Mt. Hanang, the fourth highest peak in Tanzania. The nearest town with amenities such as electricity and running water is Katesh, about five miles east. And that town is about 125 miles south of the nearest major tourist safari destinations. It’s an inhospitable land—very arid, with thorny acacia trees strewn across the landscape.

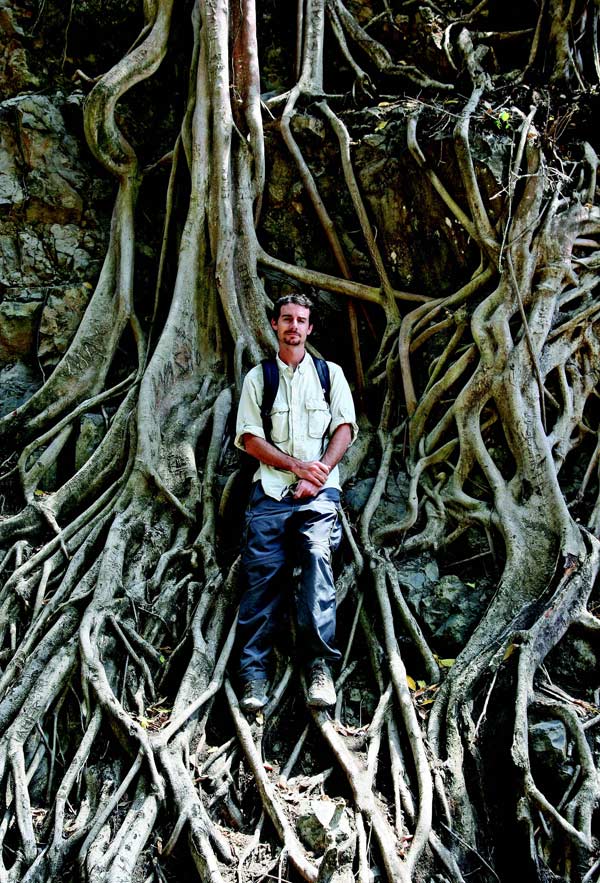

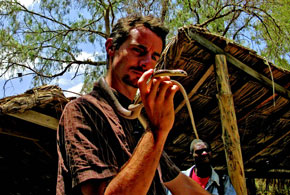

There are two rainy periods every year—the short rains in December/January and the long rains in May/June. Crop planting and harvesting must be accomplished in those relatively short periods. Other than that, it’s very dry and dusty, with dust-devils (whirlwinds) creating a permanent haze in the sky. Located only three degrees south of the equator, the sun is very intense during the day. Other dangers lurk everywhere, especially at night. The water has parasites, the mosquitoes carry malaria, venomous snakes are scattered throughout the bush, and hyenas have killed three villagers in the recent past. Every hike into the bush country is an adventure.

Two main tribes dominate the Hanang area-the traditionally agricultural Iraqqw, and the formerly nomadic-pastoralist Barabaig. The former grow maize (corn) and beans on small plots of land near their mud huts, quite a struggle in this parched land. The latter are cattle-herders who must constantly try to find water and food for their grazing herds. Cow milk and maize are dietary staples in this area. During the dry seasons, nearly every meal consists of ugali, a porridge made of ground-up corn. It’s not tasty but it fills the stomach.

Life is still very primitive with a direct lineage that goes back thousands of years. Many families live in mud-walled huts with thatched roofs and no doors or windows. There is no electricity – candlepower rules the evening in every house. There is no running water—just large buckets that are filled up ever few days from a natural springs outlet, about a half-mile north of the village. The wealth of a man is measured by the number of cattle he owns; women by the number of children they have borne.

However, the village elders realize they must make improvements to the environment. While there is very little investment capital available in these remote “barter-based” societies, the schools, clinic, water system, roads, houses, farming techniques, livestock management processes, etc. must be upgraded to modern standards. At the same time, better health care (malaria vaccinations, etc.) has already resulted in a growing population, resulting in dwindling fertile lands and more stress on the scarce water resources. I find myself caught between two cultures—two vastly different ages. I am literally witnessing the adoption, or rejection, of contemporary ideas, products, and values from the west and east, as Tanzanians choose how much of their traditional identity to keep and how much to change.

|

|

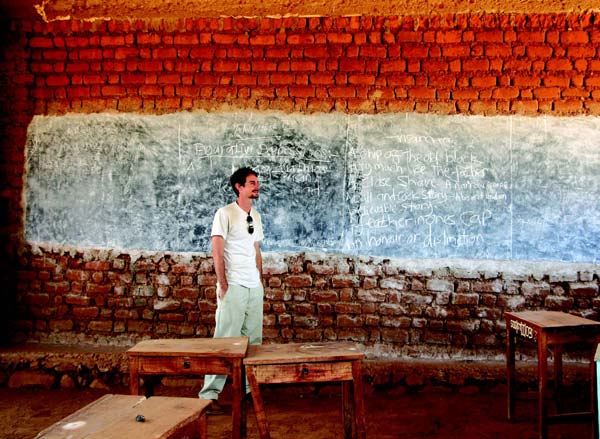

My job here is to assist this process as best I can, albeit gently, in order to not infringe on any major cultural boundaries. Although most of the daily challenges I face fall well out of my job description, there are small areas where I can make a productive difference. I’ve taught English, science and HIV/AIDS prevention at the local secondary school. I’m in the process of collecting donations to expand the small local clinic and to drill a well, which would provide year-round, high-quality water to the villagers for the first time. I’ve taken farmers on technical exchanges to learn new agricultural techniques to improve crop yield and reduce water usage. The response from the villagers has been enthusiastic, which justifies the investment of American tax-dollars for my presence here.

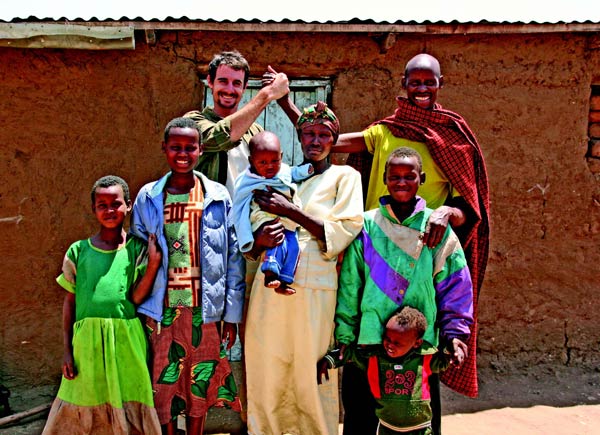

It is in personal exchanges, discussions and time spent together, where I truly feel my presence makes a difference, though. I have been blessed with many friends in my life, but never before have I appreciated the value of these personal relationships as I do here. Neighbors literally sustain each other through hard times. Even me, a “rich westerner,” can go to any house in the village and be fed any day. There is a care for life here; a strong cultural tradition that those who can feed the hungry, or help the needy, will do so. People care about and rely on other people. Family and tribal affiliations create strong bonds. This is how they have survived for generations, and this is what I will bring back to America with me.

As I watch this transformation, I am reminded of my own struggle for self-identification. I have learned from the people of Tanzania that these challenges are not problems in the sense that they require fixing, they are merely the substance of existence from which we fashion our experience; they are the occurrences which provide me the opportunity to choose who I am at that moment. Where I came to teach, I have been taught. Where I came to solve others’ issues, I am learning to solve my own. I am choosing how much of my past to bring with me into the future, and what the new values and practices are which I wish to incorporate into my current being. For me, life is now about self-creation rather than self-discovery.

This article represents the personal views of Randy Fish, not necessarily those of the U.S. Peace Corps.

|

|

RANDY FISH