ALIVE Book Review by Robin Fahr

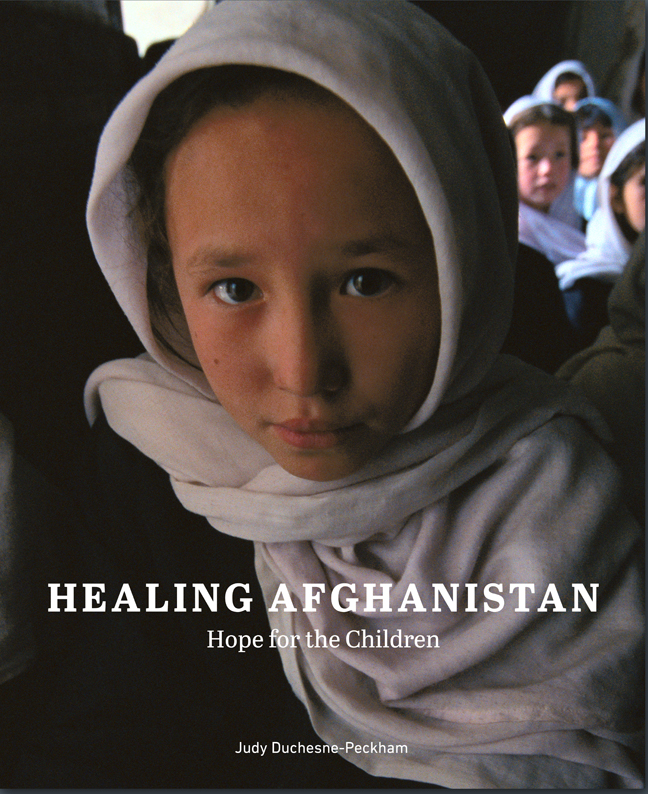

Healing Afghanistan: Hope for the Children By Judy Duchesne-Peckham

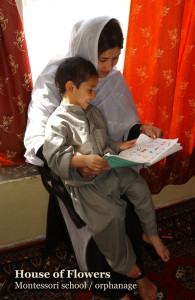

The story of House of Flowers, the only Montessori school/orphanage in Afghanistan

In 2003, Judy Duchesne-Peckham, award-winning photographer, educator, and long-time social activist, joined a small humanitarian team headed for Kabul, Afghanistan. The mission was to provide aid to Afghan women and some of the country’s estimated two million orphaned children.

Duchesne-Peckham photographed and documented both the prevailing despair in the large government orphanages and the beginning of hope in one small Montessori-based orphanage/school, the House of Flowers. Here, Afghan teachers were being instructed in Montessori techniques that encourage the healthy development of the whole child, including peaceful conflict resolution, gender equality, and respect for the individual as well as the group. At first, much of the philosophy seemed antithetical to the Afghan perspective, in which children are seen as being capable of very little. The critical importance of the Montessori approach was stressed to the Afghan staff; the children would maintain their freedom to engage in their areas of interest, producing works that reflect their temperament, intellect, and emotions. Ten years later, the verdict is in: the House of Flowers is a resounding success and is being hailed as the model for all government-run orphanages in Afghanistan.

Healing Afghanistan is about the institutional transformation now under way in Afghanistan and the ways in which it is serving to teach, nurture, and heal the children. Filled with beautiful photographs and thoughtful essays, it tells the story of a country once renowned for its educational system, the effect of the Taliban takeover which closed half of the country’s schools and made education for girls illegal, and how in the midst of chaos, there is a sanctuary of hope for it’s children.

ALIVE Magazine sat down with Healing Afghanistan photographer and contributor Judy Duchesne-Peckham to find out why we should care about the ongoing humanitarian crisis in Afghanistan and why she believes its children are the best defense against the return of darkness and oppression.

ALIVE Magazine: Why did you create this book?

Judy Duchesne–Peckham: Of all the countries I had ever visited throughout the world up to the time of my first trip there in 2003, Afghanistan affected me the most profoundly. That still remains true approximately 34 countries (total) later. I had never been anywhere that was currently at war – and had been for more than 20 years. The suffering, as well as the resilience and strength, among ordinary Afghans was palpable and often brought me to tears. It also compelled me to think of ways that I, as a middle-class teacher and photographer in California, could help. Once I met the children and staff at the House of Flowers Orphanage/Montessori School in Kabul, I knew that my efforts on their behalf could make a real difference.

Most of the news we get in the West about Afghanistan is negative. I wanted to share something hopeful and positive by focusing on the remarkable work being done at the House of Flowers; hence my book, from which 100% of profits from sales will go to House of Flowers.

AM: What was your objective?

JDP: House of Flowers is privately funded by a dedicated group of supporters but has always struggled to stay afloat since its founding in 2002. Though I have helped with fundraising these past ten years, it has never been enough to ensure that the House’s annual operating budget would be met. It seemed to me that with more global awareness of House of Flowers as a ten-year Afghan success story, raising $69,600/year shouldn’t be insurmountable. That sum provides care for up to 32 children/year, including monthly rent, food, clothing, school supplies, the salaries of a house manager, two full-time teachers, a cook and a night watchman! (visit www.mepoonline.org for complete details). But perhaps even more importantly, House of Flowers contributes to the critical development of well-rounded, intelligent, open-minded, and generous children who see themselves as global citizens. They are the best hope for future leaders who have been raised in an environment of gender-equity and peaceful conflict resolution. I wanted to celebrate that.

A couple of years ago, the orphanage nearly closed due to lack of funding. Also around this time, as the war in Afghanistan raged on, wildfires erupted and burned uncontrollably in southern California, where I live. I thought about the couple of thousand photographs I had made in Afghanistan stored in my house and what a shame it would be if everything burned up before the world had a chance to see unique images of the forgotten Afghan faces of war – the ordinary citizens, the women and children, the orphans, the disabled. I hoped the time was right to publish a book and use the profits to benefit House of Flowers. I contacted my friend, Dr. Mostafa Vaziri, founder of House of Flowers and its parent organization MEPO (Medical, Education, and Peace Organization) and asked for his advice and guidance. He approved and agreed to participate.

AM: Who is your intended audience?

JDP: The book is intended for anyone who believes that hope, healing, and peace can occur in the most unlikely of places. It’s also intended to show the importance of education in its power to change peoples’ hearts and minds through personal acts of courage, love, and humanitarian service. The book is also intended for people who don’t see things that way.

AM: What did you learn about Afghanistan that you didn’t know before and what personal stories and memories can you share with us?

JDP: I learned so many things that it’s hard to know where to begin. I had wondered what ordinary Afghan citizens thought about the US intervention after 9/11/2001. I asked some of them, who told me that in spite of the bombings, they were very glad the Taliban had been deposed.

I wondered what type of reception our small humanitarian team of Americans would receive. Without exception, Afghans welcomed us warmly, with generosity, kindness, and goodwill. Those with the least to give often gave us small gifts and shared hospitality over many cups of tea. A teacher I met thanked us for coming and upon learning that I, too, was a teacher, embraced me tightly, crying, “Because of your visit, I know that God has not forgotten us.”

I didn’t know my heart would be broken by much of what I observed and what a lasting impact those trips would have on me. When I think of Afghanistan, I remember so many beautiful faces and eyes filled with sadness and uncertainty.

I recall standing in Ghazni Stadium and weeping at the thought of the executions that had happened there.

I remember using my camera as a shield from the suffering I saw at the government-run Tahya–e–Maskan Orphanage where, in 2003, hundreds of orphan boys stood in long lunch lines waiting for food to be cooked in large black cauldrons over wood-burning stoves, something reminiscent of a Dickens novel.

I didn’t know there were countless numbers of dedicated individuals from all over the world, risking their lives through their involvement in NGO’s (Non-governmental organizations) in Afghanistan, doing their best to help rebuild a devastated country. I didn’t know their presence would greatly inflate local rents.

I didn’t know I would meet older women in literacy classes who were thrilled to be learning to read for the first time in their lives. I remember sitting on the floor next to one of them who lifted her floor length skirt to expose her pulverized anklebone as she pointed to it and whispered to me “Taliban.”

I didn’t know that in the midst of the dust, the noise, and the chaos of Kabul, there was a little sanctuary of hope, healing, and light at the House of Flowers. I didn’t know that I would fall in love with the children who lived there and would have become an instant mother to them all if I could have.

AM: Speak to the importance of educating girls in Afghanistan.

JDP: There’s an old saying “to educate a girl is to educate a nation” since a child’s first teacher is his or her mother. Imagine a world where everyone has the life-long right to pursue an education, where learning to read, write, create art, and think critically are ordinary and expected activities for both girls and boys — where legal jobs of all sorts are plentiful and pay enough to support families with a decent standard of living, including the basics of safe food to eat and clean water to drink — where people develop understanding and compassion and learn tolerance toward peoples’ differences — where no one needs to kill anyone who shares a divergent point of view — where men and women live in peace and friendship, not fear and domination.

In Kabul, House of Flowers is a microcosm of this idealized world. When the new government head of orphanages discovered this thriving Montessori-based program, he recognized its success immediately in the well-adjusted children who live there. An orphan himself, Mr. Sayyid Hashimi supports implementing the same type of program in the government-run orphanages. Allison Lide, Montessori teacher and co-founder of

House of Flowers, returned to Kabul last year to begin a pilot program in those very orphanages. Lack of funding, of course, is a major obstacle to its full implementation.

I’ve always believed that education is the strongest antidote to societal ills and challenges, with the infinite power to change peoples’ lives for the better on so many levels. It’s why I’ve been a teacher most of my adult life, as well as a life-long student. Though not a panacea for everything, education can certainly address the roots of problems such as terrorism and extremism. When children are loved and raised in healthy environments, when they are taught self-respect, respect for others, employable skills, and peaceful conflict resolution, they grow into healthy adults, immune to despair, desperation, and hopelessness that leads to terrorism.

The team that I traveled with on my first trip included three therapists from the Bay area – Casi Kushel, Taghi Amjadi, and Suzanne Pregerson – who specialize in PTSD therapy with immigrant populations, primarily from Afghanistan and Iran. They were able to begin a pilot program for traumatized children in the orphanages using finger puppets designed and made through a network of women established by the trip’s organizer, Diana Haskins, of the Afghan Academy of Hope.

We’ve all seen what happens when ordinary people become truly desperate. As Americans, if we’ve learned anything since that fateful day in New York City in 2001, it’s that we are truly members of a global community, no longer isolated by continents and oceans. We have a personal stake in caring about children in remote countries half a world away. What kinds of adults will they become? I am haunted by the faces of the once-young boys I met in the government-run orphanages and wonder what has become of them.

AM: What’s next?

JDP: I hope that enough books get sold to generate interest in a second and third printing so that House of Flowers never has to close its doors and can become the role model for other Afghan orphanages. I also dream of creating a sustainable educational fund for orphans who desire higher education, and I hope that compassionate benefactors everywhere will step forward and offer financial support to these very worthwhile projects.

HEALING AFGHANISTAN–Hope for the Children is available at www.HealingAfghanistan.com. 100% of profits from book sales will benefit the House of Flowers, Montessori school/orphanage, in Kabul, Afghanistan.

Leave a Reply