The creative triumph of Richard Linklater’s Boyhood will likely be acknowledged, perhaps emulated, by filmmakers for years to come. As auteurs study the structural genius of Linklater’s masterpiece they may also draw inspiration from the type of story he decided to tell, and become familiar with other films that seek the same delicate dance between life and art.

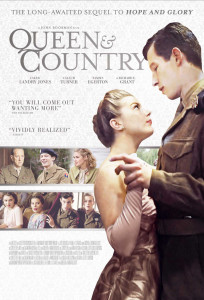

A wonderful place to start would be the autobiographical work from John Boorman, which feels like an old-school big brother to the new-millennium magic child that is Linklater’s celebrated cinematic time-experiment. Boorman, the legendary director who gave cinema one of its watershed films in terms of male psychology and cultural/class tension—Deliverance—has followed his 1987 classic Hope and Glory with a delightful and moving sequel: Queen and Country, which provides a touching and light-hearted conclusion to the story of his own boyhood, and in turn his illustrious career as a filmmaker.

In Queen and Country, the eight year old boy from the previous film, Bill Rohan (Callum Turner), is now 18 and conscripted for military service during the early 50s. Stationed in Britain as a typing instructor, he’s never part of a field battle, but his confrontation with military thought and decorum in the guise of Sgt. Major Bradley (David Thewlis) is the source of insightful humor and also frames Boorman’s humanistic philosophy. As with Hope and Glory, the sequel doesn’t pontificate or try to make any sweeping statements; it shows us the war experience through a very personal prism, an 18 year-old perspective, and predictably, for that age, it isn’t surprising when love soon trumps conflict as the boy’s primary interest.

For Bill—who never seems to covet the idea of distinguishing himself in the armed forces anyway—the event that makes a man of him is his encounter with a stunning “older woman” (all of 24) who he calls “Ophelia” because she will not reveal her identity. That very name suggests the unattainable love-object of the medieval troubadour’s noble knight who will fight to the death for her honor. Boorman’s juxtaposition of Bill’s passionate yet ultimately unrealized love for an unapproachable woman with the military-culture dysfunction he is forced to endure (and cleverly defeat, at least in spirit) produces a tone that is joyous, ironic, and bittersweet all at once. If Boorman’s memory of his first love has been romanticized by the passage of time, his moral clarity—likely formalized during the very years Queen and Country explores—remains razor sharp. This is a film born of a tender heart and focused mind, and its confidence and celebratory spirit is infectious throughout and quite inspiring at its conclusion.

Queen and Country, like its predecessor Hope and Glory, overtly refrains from making the expected anti-war statements, but the devastating effects of war become emphasized in spite of—or perhaps because of—their absence, and this is Boorman’s masterstroke. Showing narrative restraint that few directors achieve, he keeps the perspective firmly rooted in the level of maturity and personal experience of his alter-ego, which somehow makes the surrounding conflict more vivid in relief. Even if the character doesn’t fully grasp the implications of war, we do.

So often in films the story of the male protagonist boils down to his doing something courageous, something that saves or changes the world, something that elevates him, establishes him, or proves his worth. It is refreshing when a film shows us the emotional man, where the story is less about the importance or impact of his life and more about the individual resonance of it. Especially in a war milieu, where strength and resilience are often all that is required of a character, it is noteworthy to see a director brave enough to trust that a personal story will make the deeper impression.

Queen and Country will almost certainly be the 82 year-old Boorman’s last picture—he has said as much publicly, and the final shot of the film infers this with poetic charm: a movie camera slowly coming to a halt. It is heartening to see the great director go out with such grace, and the subtle insights of Queen and Country show Boorman’s singular voice in concert with mature wisdom. The metaphoric title of the film itself is both the clue and ultimate message. The triumph over the insanity and terror of war is achieved through sacrifice and commitment, not to abstract concepts like royalty or territory, but to something far more personal: love and family.

Leave a Reply