Bart Dorsa, a lifelong resident of San Jose, has lived in Moscow for six years and has achieved more in that short span of time, than most young transplanted Californians could ever hope to expect. We had emailed back and forth between Moscow and Danville to set a time for a phone interview which finally materialized when he was driving from Los Angeles to San Jose for a local event.

I had followed Bart’s interesting life in Moscow through his parents Marilyn and Frank Dorsa of San Jose, and since I’ve known him since he was four years old, I took a special interest in his life and successes abroad. I had made a list of twenty burning questions about his career in Moscow to get the article going. I should not have been surprised at the titillating answer to question number one, and I saw that the interview had taken on a life of its own.

“Well Bart, tell me about the interesting women in Moscow. Is there anyone special?” I asked.

“Did you know I was engaged to twins?” was his first question to me.

“Yes Bart, I had heard that but I thought it was a great comedic throw-away line,” I answered.

“Well, it was great while it lasted—the twins Nadia and Luba were singers in their own band and they had been dating men who were jealous of their close sibling relationship so they both decided to marry one guy. We all three got engaged. I was the lucky guy,” he laughed.

I went on to my next question about his work in Russia. It was fascinating so far, to say the least. Once Bart had settled in Moscow, it lead to his liaison as a managing partner with one of Russia’s most creative emerging fashion designers, Vika Gazinskaya, who has since found her creative niche in the competitive world of design in the Eastern Bloc countries as well as Paris.

Bart Dorsa took control of the business, public relations and production end of the seasonal fashion show extravaganzas that were soon featured in top European magazines. Even though the fashion show production end of the business was extensive, he continued shooting an artistic-genre of photography which led to exhibits of his art at local Moscow venues. His creative work was noticed, and he garnered critical reviews.

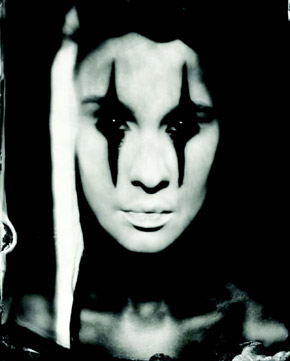

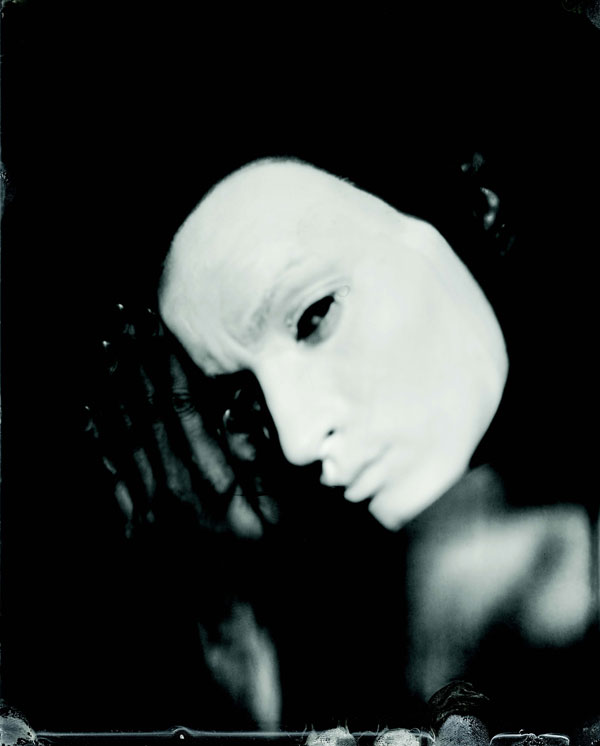

He soon ventured into a field of a new kind of photography by using an old technology with an antique tripod-mounted 19th century wooden camera. The ghostly faces in his photographs, as if the subject is peering out from the past, drew positive critiques of a most unusual old-fashioned concept that had crossed over to an albeit contemporary art form. Bart Dorsa has captured ephemeral photographic images that are hauntingly captivating with a lingering sense of the long ago past.

This highly unusual art form in the field of contemporary photography, with the use of an earlier technology, led to further recognition of Bart Dorsa as a creative artist-photographer. It was just a matter of time, after so much acclaim about the artistically surreal art form, that top Moscow models and others sought him for his unusual camera work. Dorsa shot each subject with the idea that his artistic guidance of light would allow the antique camera itself to interpret the photograph. The photographs, which are manipulated by patient developing techniques, emerge as quasi-intangible, diaphanous, ghostlike images. The photograph is captured by the fast opening of the shutter for a few seconds—a fraction of a moment trapped in time—which is already in the past within seconds, with an image that could endure for ages.

Bart Dorsa conceptualized that a total immersion in the visual art form was integral to the ethos of his photographs. It was a no-charge, no-pay venture and some of the eeriest images of Moscow’s beautiful women, and those not necessarily photogenic, were artistically captured this way as if they reach to the present from the century past. The results are eerily unearthly, to say the least, but bear a fleeting gossamer grotesque beauty that cannot be achieved with textual mainstream photographic techniques.

When I asked Bart if the Russian women are more sophisticated at an earlier age than their American counterparts, he answered, “The Russian women develop a classical femininity at an early age which is then very restricted. They are beautiful and sophisticated in their look, but are still very young.”

I asked him to describe his daily routine in Moscow and he told me that he is working eight to twelve hours a day in preparation for his one-man photography show at the museum. “I try to get at least six hours of sleep every night. The people work hard in Moscow and hard work is expected. The summers are humid and uncomfortable and the winters are bitterly cold – freezing bitter cold. The Russians work hard and they play hard. And the most noticeable difference about the Russians from the Americans is their excitement about simple everyday things—they are passionate about everything and do not have the chronic cool detachment we see in America. They get intensely excited about the little things and enjoy every aspect of life to the fullest.”

“Speaking of bitterly cold weather, Bart, how do they feel about global warming? Is it an issue? Is it ever discussed? Should I dare even ask,” I enquired.

“They’re celebrating global warming! It’s so cold over there; they love to hear about the normal cyclic warming. It’s nature at its best.” We laughed.

“Are the Russians outwardly concerned about their political climate?” I thought I already knew the answer to the question, but I asked anyway.

“Moscow is a city of twenty million people and they gently accept what’s going on. They’re not impassioned about their politicians; there’s not much they can do to change anything, and the Russians are famous for their stoicism. They go about each day, stoic in their beliefs, and they live hard lives in dangerous cities. Besides, I don’t get into talking much about Russian politics. Life is hard in Moscow, as elsewhere. Many people have lost their investments and their jobs. There are big pay cuts and there is daily hardship, but the people continue to live their lives and go to work every day. Their tradition of stoicism is that life goes on.”

Bart Dorsa has a different outlook on life and his work in Moscow now. He is more impassioned than when he was producing and directing films in Los Angeles. His film The Invisible made an appearance at the coveted Robert Redford Sundance Film Festival and the once-dormant Here Lies Lonely is soon to be released. The production end of his film work was what gave him the artistic impetus to work in still-photography in Moscow. After his rapid success in that field he gradually moved away from the medium as a digital camera photographer and artistically ‘regressed’ to the photographic technology of the past that was first introduced in 1839.

Bart is now working mostly with the antique mid-19th century collodian or ‘wet-plate’ camera. “I can work in the middle of nowhere and I don’t need to depend on anything from the outside to complete my project. It makes me fiercely self-reliant and independent.”

I always knew that about Bart.

I always knew that about Bart.

The antique camera offers difficult challenges and a special expertise of infinite patience. The camera is large, heavy and bulky and is housed in a wooden box on a pedestal with a black cloth to block the light while the photographer shoots the photo. Bellows move the lens forward to the subject, the glass plate is placed in a slot and the image is exposed on the glass and within seconds it needs to be developed from a negative to a positive. That is how the very first facsimile images were captured on glass or on tin plates one hundred and seventy years ago. This process required developing-chemicals such as the syrupy solution of pyroxylin in ether or alcohol and other complicated flammable mixtures that were very different and much more dangerous than today.

The collodion process, introduced in 1851, takes a slow and accurate technique. It requires a special patience and a step-by-step process, far beyond the f-stop photography that preceded today’s digital cameras that have made the art of photography somewhat boringly instantaneous.

“The antique camera gives me more artistic control and I can do all my own developing by creating my own formulae with emulsions of collodion, cyanide, ether and other chemicals. I create my own chemistry to make the photographs on glass. None of the developing processes need any dependence on outside sources. It is an independent and resourceful procedure. No single regular commercial product is needed to create the photographic art. It is a process that I work on from the making of the image by exposure on glass to the final end product,” Bart Dorsa explained.

“People face failure everyday and we are always in a creative crisis—meeting the challenge and succeeding is an irreplaceable reward. My work takes me away from the chaos of life. It is very rewarding, even though my hands and feet are black from the silver used in the process.”

Photography has recorded our lives for seventeen decades, not long in the grand scheme of visual art, by any means. The dawn of photography emerged almost simultaneously in 1839 when several scientists were able to create a method of fixing an image by allowing light to be transmitted through a camera lens that left a mark on paper or sensitized glass plates. The camera oscura—Italian for dark room—evolved to fruition by the incremental expertise of Nicephone Niepce, Louis-Jacques-Mende Daguerre and William Henry Fox Talbot who together set the technology in non-stop motion.

A few years later Frederick Scott Archer invented the first practical wet-plate photographic process to be reproducible when he coated a glass plate with a collodion solution and

exposed the plate while still wet. Voila! By 1880 George Eastman perfected the dry-plate process, and the Eastman-Kodak Company has since clicked its way into photographic

history cornering the world’s market share of photographic papers and film.

Photography developed, since 1839, from the primitive technology of the tripod-mounted wooden camera with a bellows and black hood, to the box Brownie, the f-stop wonder Rolliflex camera and to the recent palm-sized models that give us the instantaneous results.

My curiosity, about the almost-extinct cameras, led me to ask Bart what had inspired him to pursue the cumbersome technique-driven and archaic 19th century methods of making primitive photographs with such a time-consuming and patience-taxing set of challenges.

“Bart, why did you revert to the old-time cameras? Is it not more difficult to work with such archaic technology? What inspired you to make your photographs with old cameras?” His

answer was actually quite surprising to me.

“I saw the haunting images of Lincoln and a man named Powell at the National Archives in Washington D.C. and became mesmerized,” he answered.

The avant-garde, yet ethereal classic style of photography that Bart Dorsa has created with definitive modern nuances, and with the use of an archaic mid-19th century camera has

received the coveted attention of the curators of modern photography at the Moscow Museum of Modern Art—the MMOMA. The MMOMA has a substantial permanent collection of 20th century artists such as Pablo Picasso, Fernand Leger, Joan Miro, Marc Chagall and Kandinsky that are exhibited at their main museum in addition to their other three venues in the historic quarter of Moscow.

|

|

Bart Dorsa, an American artist, has been given the honor of having his innovative photography exhibited in a one-man show at the esteemed MMOMA, and his 120 piece iconic photograph collection will be installed near the year’s end by the museum with special lighting effects at one of the historic museum buildings.

Bart Dorsa has defined the essence of photography from the 19th to the 21st century by taking a fresh innovative artistic approach, much like prior exhibitions, Soul Stealer and Silver Tongued Devil. His pioneering work has taken him on a quintessential photographic journey of one-of-a-kind haunting images with eyes of clarity that search from the distant past to the bright light of the present – their ghostly souls captured maybe for forever in a brief ethereal moment of time.

THE PHOTOGRAPH: A MOMENT IN TIME

It is true that early images of people and those photographed during the American Civil War have an eerie haunting quality to them. The faces are devoid of expression and there was never a smile when the sitters looked into the foreboding camera. No doubt it was their first time facing a wood box which was purported to capture their very images. The exposure—lens aperture for light—took a long time and the subject had to sit unsmiling and very still for a few minutes so the image would not blur by the long exposure time. The period of immobility is what led to blank stares along with the trepidation that the photographs were to be carried far away by family and perhaps were never to be seen again.

It would remain the only remembrance of their image.

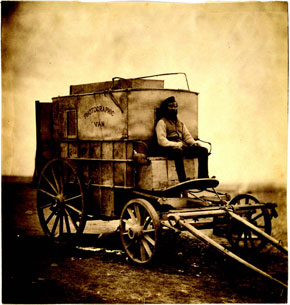

During the Civil War, soldiers were specifically photographed in the battlefields as a tangible reminder that they were proudly fighting a war and their images would serve as souvenirs. Very few people could afford a photograph as the cost was equal to a week’s pay. Traveling photographers made daguerreotypes of soldiers who may very well be dead before the images were developed in the horse-drawn ‘dark room wagon.’

It was not the first war to be recorded with photographic images; Roger Fenton was the earliest traveling photographer sent on assignment to the battlefield in the1853-1856 Crimean War. He bought a horse-drawn wagon from a London wine merchant and rigged it as a mobile dark room van and shipped it on the Hecla, a troop ship that sailed to the Crimea in the Black Sea. Fenton was the first photojournalist to ever be embedded with troops on the battlefield for three months in 1855.

Fenton produced 360 photographs in the Crimea during his three-month stay, an enormous achievement for an on-location war zone, camera set up and instant developing. His assignment was to omit images of misery and tragedy and capture only patriotic images of generals and COs in battle dress to appear victorious for the front pages of London’s newspapers. It was to be the first recorded photography used as visual propaganda for the British war effort in the conflict against Imperial Russia with the French, Turks and Sardinians as allies. The Crimea was the location of the iconic Charge of the Light Brigade where over six hundred British and Irish men charged into the wrong valley and into the cannon fire of twenty thousand waiting Russians.

Roger Fenton moved on to Moscow after the war to photograph the city’s spectacular architecture, but will always be remembered for his haunting images of battle-dressed British generals, French Zoaves, and conical field tents spread across windswept Crimean battlefields.

The realities of war, through Fenton’s photographs, lead to a widespread negative reaction by the British public and many of the historic photographs were liquidated at auction. In 1944 the U.S. Library of Congress purchased 263 of Roger Fenton’s photographs from his grand niece and the historical collection can be viewed in their online archives: LibraryofCongress.org.

Photographs copyright Bart Dorsa

ANITA VENEZIA