It is just past 5:15 A.M. as I make my way into the kitchen to make a pot of coffee. I walk to my desk to boot-up my desktop and glance at my iPad as I’m waiting. An internal conversation begins: “Okay, one brief look at my games won’t hurt. I’ll just check to see where things stand. I will hold fast to the rules I’ve set for myself: No moves before I’m fully awake—well past my first cup of hot caffeine and thinking clearly. Yeah, no problem. Everything looks good in all… wait… wait… did he really move there? Let’s see, this guy is in Spain, right? What’s his rating again? Oh, yeah, he’s a “1323.” Ahh, yes, he doesn’t see what’s coming over here… I’ll just move her (my Queen) up here…”

As soon as my finger leaves the screen, I see…the mistake. Now the thought is, “Oh, no, this blunder will cost me.” I have work to do so I leave the board as it is, but in the back of my mind throughout the day, the thought creeps into my consciousness: What can I do to fend off what looks to be certain defeat?

And so it goes when you’ve been infected with a virus more virulent than the swine flu—of course, I am referring to the game of chess, and the symptoms I describe are not the least bit uncommon for those who love to play.

Now please understand, the severity of my ailment is mild. I don’t check my games in the middle of the night, and never play—okay, not really never, but rarely—during the day when I am working. (The exception being, perhaps, while waiting for a large file to upload or download).

The term “obsession” is sometimes used when referring to chess, and for some, this is a self-confessed truth. For example, the well know, Pulitzer Prize-winning author, syndicated columnist and psychiatrist, Charles Krauthammer, gave up the game all together because he realized he had developed a bona fide addiction, finding himself at the board in he middle of the night.

I don’t have one iota of statistical evidence to suggest that OCD is more prevalent amongst chess players than anyone else, but I suspect this may be true. As online chess has opened a doorway into the habits of scores of players, with their record of wins, losses and draws revealed, the staggering numbers of played games suggests that chess may well be the grand daddy of “harmless” addictions.

First Moves

My older cousin, Jim, taught me the game of chess when I was ten. For the longest time, I was sure he was one of the world’s top players, as he could always beat me handily. The chess pieces of his set were the same ones used in the original Star Trek television series,* which somehow confirmed that he really was as smart as Mr. Spock—same chess pieces, he beat me all the time, and he often uttered phrases like, “that’s logical,” or, “fascinating,” or, “how illogical.” And come to think of it…his ears were sort of “pointy!”

I liked playing chess, and I’d played whenever we visited my aunt and uncle’s house. I was soon playing well enough to teach my father the basic moves, and for a while we played pretty often. Once he had the moves down, he usually won, but I was still able to win a fair share of games, too. That is when I realized that, unlike sports, age and physical characteristics had nothing to do with one’s ability to play well. The only thing that mattered was the ability to concentrate and think.

In the eighth grade, I joined the school chess club, and while it wasn’t a chess “team,” with formal competitions, per se, I was able to experience playing chess with a number of other kids my own age. It was here that I discovered that psychology was sometimes a part of the game—something which I really didn’t really care for because to me it seemed to pollute or tarnish what I thought to be a “pure,” clean game. You should be able to win because you play chess better than your opponent, not because you evoke fear in him. (I later learned that there is really no way to separate the two—chess from personality.)

Throughout high school, I played chess off and on with my dad and a few friends, and followed daily chess problems, authored by International Master, George Koltanowski*, in the San Francisco Chronicle, but outside of this and schoolwork, ninety-nine percent of my attention was focused on a few other things—those being my 68 VW bug, Friday nights at Pinky’s Pizza and “cruisin’ the creek,” and cheerleaders. That is, until my junior year…

1972: The World is Changed

People often credit (rightly so) President Ronald Reagan’s SDI—the Strategic Defense Initiative, aka, “Star Wars”—as a primary catalyst for the collapse of the Soviet Union. But there were other, less recognized factors that also played a significant role in scuttling the juggernaut of global communist influence.

Long before SDI, a crushing blow to the Soviet psyche came on July 20, 1969, when Neil Armstrong’s boots kicked-up dust on the lunar Sea of Tranquility. America’s “Cold War” with the Soviets that had simmered for nearly 30 years, was beginning to turn in favor of the West. Three years later, in July and August 1972, in the windswept city of Reykjavik, Iceland, a twenty-nine year old American named Robert James Fischer, single handedly inflicted a gaping wound into the façade of “Russian superiority.”

To fully appreciate the significance of Fischer’s triumph, it is important to understand that the Soviet Union had been an overwhelmingly dominant force in chess since 1948.

Much like Soviet participants in Olympic events, chess players in Russia were encouraged and supported by the state. Chess was used as a propaganda tool; the idea being that the game served as the “demonstration sport” of mental superiority and intelligence. All elementary and secondary school children learned chess as part of their regular curriculum, and promising players were treated to weeks-long chess summer camps and chess-centered boarding schools. The state rewarded strong, competitive players, and afforded them, by Russian standards, a “celebrity lifestyle.” Soviet society was encouraged and culture molded to value chess, elevating it into a vehicle for the attainment of a revered social status. Since 1948, until a young prodigy named Bobby Fischer faced off against the then current world champion, Boris Spassky, every other world champion had also been Russian.

Unlike in Russia, prior to this landmark championship match, chess was of little interest to most people in the United States. But Bobby Fischer changed that. His brilliance and mastery at the board was undeniable. In 1956, at the age of 13, we won the U.S. Junior Championship and placed 4th in the overall U.S. Open Tournament in Oklahoma. At age 14, he won the U.S. Championship, beating the Russian, Samuael Reshevsky, becoming the youngest U.S. Champion in history. In 1958, at just 15, he became the youngest grandmaster in history. At 19 he was undefeated and won first prize in the 1962 Stockholm Interzonal Tournament. In 1970 he crushed Soviet ex-world champion Tigran Petrosian in the “USSR vs the Rest–of-the-World” Tournament, and in 1971 he demolished the three top grandmasters in the Candidates Matches. There was only one title that remained unclaimed by Fischer, and he wanted it badly—the world chess championship.

In 1972, the stakes could not have been higher as the political implications for a face to face showdown with the Soviets was undeniable. The back-and-forth posturing and rhetoric between the communist USSR and capitalist USA, while not as high as during the Kennedy—Khrushchev years, was still the dominant global rivalry.

Fischer hated the Soviets and had openly accused them of systematic cheating over the years to retain their dominance in chess. In a BBC interview, he said, “It is really the free world against the lying, cheating, hypocritical Russians—this little thing between me and Spassky. It’s a microcosm of the whole world political situation.”

The Russian government desperately wanted Fischer stopped once and for all, and the U.S., while to a lesser degree, also realized that a Fischer win have some significance. The Fischer-Spassky match would be the intellectual prize fight of the century, leaving the winning competitor, along with his nation and ideology, with major bragging rights.

Posturing, psychological warfare, and all manner of shenanigans preceded the match, particularly from Fischer, but it finally got underway on July 11, 1972. Fischer had been holding out for more money, but a telephone call from then Secretary of State Dr. Henry Kissinger convinced Bobby that fate of Western prestige rested upon his willingness to play and his ability to beat the Russians.

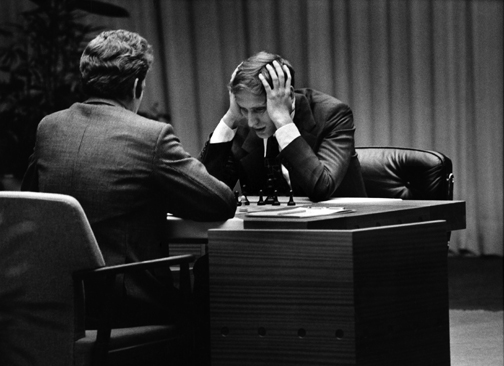

The final game was played on August 31st. The two titans played a total of 21 games. Fischer lost the first two games after making incredible, severe blunders. But in game three, the “Deadly Gamesman,” as he had been called on the cover of Life Magazine prior to the match, emerged. In the next 19 games, Fischer won seven and drew eleven. He lost only one.

While chess had been of major interest for many years in the Soviet Union, for the first time, during and after the match, chess became hugely popular in the United States. Chess suddenly became “cool” in the states, as the nation rallied behind Bobby Fischer. The chess match was so popular that by the 13th game, in August 1972, according to news reports at the time, in Manhattan, 18 of 21 bars had their TV sets tuned, not to the New York Mets game, but to channel 13, the New York public television station, with live coverage of the Fischer-Spassky match from Reykjavik. News reports from the democratic Presidential Convention were postponed so that the chess match could be broadcast. This particular show gained the largest rating ever recorded for any public television broadcast.

In the end, it was a conclusive victory for Bobby Fischer, for the West, and for chess itself. The news agencies that had converged on Reykjavik had played up the “David vs Goliath” scenario perfectly, and Bobby came home a bona fide hero. He was featured in Time, Newsweek, Life and Sports Illustrated, and was a frequent guest on the major talk shows of the day.

On a personal level, after so many years of seeing chess relegated to a backseat behind more “macho” pursuits, like baseball and basketball, it was gratifying to see chess emerge to a front and center position of not only acceptance, but outright popularity in the United States. After the “match of the century,” the sale of chess sets and chess books skyrocketed, and to this day, more books have been published about chess than about all other games, combined.

Other than Bobby Fischer, no other American has held the world title in chess, and outside of the chess playing community, his name is recognized and associated with the game above all others.

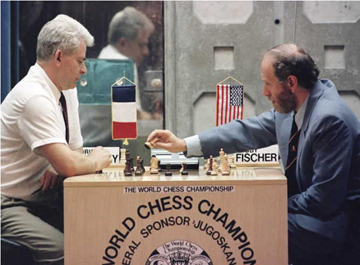

Sadly, the story of Bobby Fischer’s life did not end well. He failed to show up to defend his title a few years later and essentially became a recluse. He returned briefly in 1992 for the “Revenge match of the Century,” with Spassky, only to win again with 10 wins, 15 draws and five losses. The match was played in Yugoslavia however, and Bobby’s travel there then was in violation of United States law. Fischer had called a news conference before the match, and in front of the press, spat on the U.S. order forbidding him to play, proclaiming, “This is my reply.” An arrest warrant for Fischer was issued by the United States, and he became a fugitive from his home country for the rest of his life.

Fischer became increasingly paranoid, bitter and unhinged, living the remaining years of his life in exile, in the only country that would grant him asylum—Iceland. He died of renal failure on January 7, 2008, because he refused medical treatment, and was buried near a small church in the same city, Reykjavik, where he had experienced the pinnacle achievement of his life.

Because of the “Match of the Century,” like other chess players around the world, my interest in and appreciation for the game of chess, grew. The fact that Bobby Fischer eventually went mad was a profound loss to the game of chess and to the world. When I heard of his passing 2008, it seemed like such a waste.

Bobby Fischer’s only passion in life was chess, and his need to beat the Russians was inexorably woven into the fabric of his identity. In his mind and in truth, from July 1972 and beyond, the world had cast him as the central figure in an event that changed the world. It was a role not even the greatest grandmaster of all time could bear.

SIDEBAR

Were the Russians really smarter than everyone else? The fact is, there were simply lots more chess players in the Soviet Union than anywhere else in the world, and they all started playing at a very early age. For example at the peak of Soviet chess domination in 1980, there were over 4 million members of the Russian Chess Federation, while there were fewer than 200,000 members of the US Chess Federation. With that many players, you’re bound to have at least a few that are really, really good!

*The chess set shown in the original Star Trek episodes is a Peter Ganine Classic Set, produced in 1961. These sets are now quite rare. The only one I have ever seen since my cousin’s set is one on ebay, listed at $1,500.00.

*George Koltanowski (1903-2000) is the world record holder in “Blindfold Chess.” In 1937 he made headlines by playing 34 games simultaneously while blindfolded. In 1960, in a demonstration exhibition, he played 56 consecutive games while blindfolded, winning fifty, drawing six, and losing none!

For more information about chess, visit the United States Chess Federation website at uschess.org

For information and links to local chess clubs, visit the USCF Northern California Affiliate, at calchess.org

To play chess online, visit chess.com and on ipad or iphone, download the Social Chess app.

Leave a Reply