Sometimes, getting words down on paper is like watching a hummingbird as it flits from flower to flower, trying to find nectar. As soon as one thought appears, another pops up beside it, turning your mind in directions that you never expected. Or, it’s like driving along a twisted road that you’ve never before traveled—while you expect each turn that meets you head-on, you’re never quite sure of your ultimate destination.

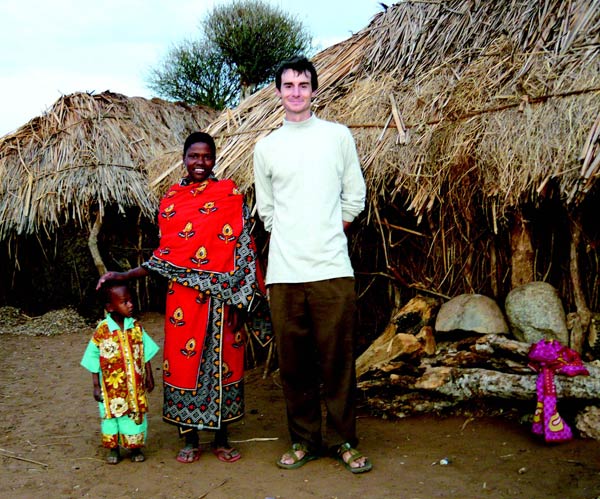

So it is with this story. It began simple enough; my wife Peggy and I were enjoying some casual conversation over lunch with friends, Bob and Jennifer Fish. As we discussed our families, they told us about their son, Randy, who is working as a Peace Corps volunteer in Tanzania. The more we heard about Randy’s work, the more intrigued we became. The idea of running a story in ALIVE was broached, and the direction seemed clear enough; we would do an article about how a local resident, Randy Fish, was helping people in a small Tanzanian village.

On the surface, one would expect the story of how a comparatively wealthy, educated westerner was working to “improve” conditions for people living in an impoverished, technologically backward village in Africa. But, as you will discover by reading Randy’s own words, the story of his work in Tanzania is deeper and more complex than one would assume. More than a story of service, it is a story of comparative values; of bridging cultures and seeking the common ground of compassion in cases where that bridge stands incomplete. More than anything else it is a story of self-discovery, understanding and empathy.

Snapshot of the Peace Corps

You remember the Peace Corps. They used to advertise fairly regularly on television during the 1960s and 70s. Until hearing Bob and Jennifer share their story about Randy’s experience, I would have to say that my image of the Peace Corps was pretty much formed through recollections of those old TV commercials—an image born alongside memories of the Vietnam War and the protests against it. Cast against the stark contrasts of that era, I suppose I envisioned the Peace Corps as just another government program, a feel-good enterprise, perhaps, being offered up to the world as a way for the United States to be recognized as a “good” nation.

While the Peace Corps is an agency of the United States government, my understanding of its purpose and value, has been what could best be described as superficial. And while I still retain a healthy skepticism when it comes to the real worth of just about every agency of our government, as I have come to know the story of Randy’s experience, I have gained an appreciation of this organization and how it functions that is different from what I assumed.

The idea behind the Peace Corps was first proposed in a somewhat impromptu speech delivered on October 14, 1960, by then Senator John F. Kennedy, to students at the University of Michigan. Perhaps as a warm-up to his famous “Ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your country” inaugural, Kennedy challenged the students to serve their country for the cause of peace, by volunteering to work and live in developing countries.

The students were enthusiastic about the idea, and on March 1, 1961, President Kennedy signed an executive order creating the Peace Corps as an agency of the United States government. By 1966, there were 15,000 individuals serving, and since then, more than 195,000 Peace Corps Volunteers have served in 139 countries throughout the world.

Currently, 7,876 volunteers are working at 70 different assignment posts in 76 countries. They work in myriad ways, applying their skills to a broad spectrum of needs. Volunteers are involved with farmers and small business owners, helping them develop ways to be more productive; they serve as teachers to both children and adults, and they aid entire communities in countless ways. Service in the Peace Corps is a commitment of 27 months.

Randy’s Life in Tanzania

After reading Randy’s first hand account of his experience as a Peace Corps volunteer in Tanzania, I wanted to know a few more details for our article. Randy’s father, Bob Fish, arranged for me to call Randy at 10:00 A.M. While there is no electricity or land-line telephone service in the village of Dawar, Randy does have cell phone access powered by a solar charger. With the time difference being ten hours, making it 8:00 P.M. Tanzania time, it was a fairly convenient time to call.

I asked Randy to elaborate about his mission as a Peace Corps volunteer. Certainly, he went to Dawar with the expectation of helping people improve their lives. In that context, I asked Randy to tell me about how the people of Dawar are reacting to his efforts there. One big question I had was, why is it that a group of people, who have existed for what is possibly thousands of years, remain so technologically behind the rest of the world? Why does poverty and their primitive lifestyle persist, despite the efforts of so many outsiders who have tried to help?

Randy: When I first came here, that was the idea. I’m coming to make things better—to help people and to change things. But what I found was things are changing but they are changing at their speed. They are deciding what to change.

I’ve learned that there is no ‘better’ really, there is only a ‘different’ way. Some ways produce more than others. Some ways, you do get a lot more corn for example, but it also takes a lot more time—which is less time to spend with your family. It’s less security because you might have to invest a lot of money to buy seed, let’s say, and then, if a drought comes, it’s much less of a benefit. You spent all that capital that normally you wouldn’t spend, and you get no return. So, instead of that, they would rather spend very little capital and get a smaller return than take a big risk and not know about the return.

It’s a very ‘Tanzanian’ trait-not to assume risk.

There is very little security in day to day life here, so any time you give up a little bit of that security and try to get a reward later, that’s a very shaky proposition.

EJ: Is corruption involved here that helps create the technological disadvantages suffered?

Randy: Corruption is very bad here. For example, you could invest a lot of money to send your kids to school, but the teachers don’t show up. People are very disenchanted with the institutions in place. Institutions that have, in the past asked them to invest and take risks, in the past those institutions have let them down. The risks they’ve taken didn’t bring the profits promised, so there is a lot of distrust now in promises, especially from outside influences.

EJ: So, it’s more outside forces involved that hold the people back?

Randy: Corruption is very much within the village itself. For example, there are really three smaller villages within a larger village. They decide to assess a tax of ten dollars per family to finance a water system, but then you have a corrupt tax collector and the money disappears. I pick who I work with very carefully, especially with money. And often, it’s even your neighbor or even your best friend that will steal from you.

EJ: So how do you deal with that? How do you help these people?

Randy: My goal is to help those who want to change—to help those who want to help themselves. I’m not an agent of change, I am a motivator of other agents of change.

One thing I really want to stress is that when we first come here, we have this idea that there is this thing called a ‘community’ and that we are going to go and help the community. But that’s very much a fallacy. It’s individuals that we end up touching and who end up touching us. And it’s the same, I would venture to say, for every Peace Corps volunteer. You get on a very individual basis—it’s personal relationships that it’s about.

EJ: What, if anything, surprised you most, about living and working in Dawar?

Randy: One thing that surprised me—the biggest difference—is just the closeness of families here. Families and neighbors. They have a saying here, “It’s better that a far away family member dies than a neighbor.” Because you are very close to those around you. Communities are so interconnected—so many inter-personal relation-

ships, and they rely on each other so much. Time has shown them they can’t rely on the government or on outside influences. People rely on each other.

Social relationships are very strong here. For example, if you’re visiting, it’s considered rude if you’re not offered food. In the U.S., if someone comes to your door at dinner time, people say, “Come back later. We’re eating.” Here, it’s, “Stay. Eat.” Food is one thing most families have and they share it.

EJ: Do you miss home and your family? Things like being able to jump in your car whenever you want to go somewhere, and electricity and running water and being able to take a shower?

Randy: I don’t really miss it, but I’d have to say that I have a greater appreciation for the time when I do get to be with family. I love it here. I love the peace and quiet. I love the stars. I love that you don’t know if you’re going to be able to shower tomorrow; if water’s going to be available. There is something nice about being unsure of

what’s going to come. My desire is not to return to America, my real desire is not to forget—not to forget what we’re really doing here.

EJ: What would you tell school kids back in the States? What would you say about your experience and would you recommend it?

Randy: I’d say there are all types of education. A very important one is in the classroom. But you can’t forget to go outside. You can’t forget to learn from yourself and that you can be your own teacher, or that there are other teachers outside of school. I’d say, learn as much as you can and experience as much as you can. Just live your dreams.

How to Help

EJ: What, if anything, can ALIVE readers do to help you in your efforts?

Randy: The maternity ward is the big project that I’m trying to help this community—my village—build. I’ve written a Peace Corps partnership grant proposal which allows private donors from the States to contribute money through a Peace Corps fund that will go directly to this community and this project. There will be a link on the

Peace Corps website to donate to this maternity ward in my village.

Information about the Peace Corps can be found at their website at www.peacecorp.gov or at their toll-free recruitment number 800.424.8580.

ERIC JOHNSON