Book Review by Robin Fahr

Being an ALIVE Magazine book reviewer as well as a television talk show host, I’m in the enviable position of getting to read great works, both fiction and non-fiction, and then getting to interview their authors, face to face. When I interview someone I really like, I automatically love their book, but in the case of Vietnam War Veteran Kenneth Levin, whose third book, Salami and the White Horse, has just been released, I’m fairly certain I would have loved it anyway.

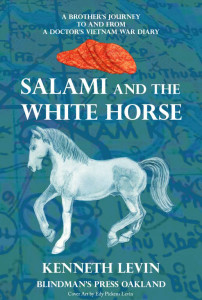

Levin is the author of the novel, Crazy Razor, and a short story collection, The Many Deaths of Comrade Binh, both fictional yet based on actual events that occurred during the Vietnam War. Salami and the White Horse is his first non-fiction work, based on an army doctor’s Vietnam diary, discovered nearly five decades after the last entry.

Levin is the doctor’s brother, who read the diary and reluctantly started a journey which has taken him from the late 1930’s to today, from Chicago’s West Side to Vietnam, from birth to death, from tears to laughter, with plenty of painful and warm memories along the way. Salami and the White Horse describes this journey where interpersonal relationships, family, sibling rivalry, narcissistic brilliance, love, and humor are presented in a bittersweet, unvarnished, and gritty narrative – a roller coaster ride of tears and laughter.

Levin just returned from his National Book Launch in Miramar, where his wry style and quick wit appealed to audiences of all ages, with special emphasis on veterans and their families. We recently caught up in-studio and again in-livingroom:

ALIVE Magazine: After a novel and then a collection of short stories of war and Vietnam, your third book, Salami and the White Horse, recently premiered in Florida, ground zero for Veterans, it seems. The launch was a huge success, attended by all ages, perhaps because Salami is as much about family and history as war and Vietnam. Is this a shift in your writing?

Kenny Levin: Shift? Maybe so. Probably more like a burp. It is non-fiction through and through, whereas Crazy Razor and The Many Deaths of Comrade Binh are fiction. Or at least they have thin veneers of fiction layered on top of cores of fact and reality. There is no veneer on Salami.

AM: You take your readers for a ride on an emotional roller coaster. I laughed and cried. What compelled you to write a book like this?

KL: If my writing can produce tears and giggles, I’m satisfied with my work. What first compelled me was what I thought would be a good book for very little effort on my part. I had my brother’s diary from his time as an army doctor in Vietnam. I thought that all I’d have to do is transcribe it, add a bit of narrative between entries and, voila, an instant book. That was one of my dumber moves. It was so boring. Then I found the diary of a North Vietnamese doctor who set up a clinic not far from where my brother was stationed. I turned the book into a comparison of the two diaries. Still boring. So then I added a bit of the two doctors’ history, and it was a little bit better but still lousy. It was at this stage where one of the early draft readers, a clinical psychologist, suggested I focus and expand on the family dynamics that I had brought in as part of my brother’s history and add more about the politics of the time. That transformed the book. By the time I finished, catharsis and telling a tale of family were the compelling factors. The easy book with little effort on my part was long dead.

AM: How did you come up with that title?

KL: Before I started writing Crazy Razor in 2009, I read a “how-to-write-a-book” piece put out by some writers’ workshop. The first direction was to pick a title before you start writing. That is possibly the worst advice you can give anyone who wants to write. When I start to write – and I’m not alone in this – I have only the vaguest of ideas where my writing’s going to go. How could I name a book before I know what the book is about? Salami and the White Horse went through two complete revisions and then 13 drafts. It went from a transcription of a doctor that just happened to be my brother’s war diary, to a comparison of two doctors’ war diaries, to a book of family dynamics and political history, until finally it became a combination of all of that. The focus of this unfocused book is three men: my brother, my father, and me. My dad was a salami fiend. He could live on salami supplemented with chocolate and be quite happy. My brother was the crown prince of the family. Brilliant, charming, good looking. And what did a crown prince travel on? Certainly not an Oldsmobile. Prince Charmings sit astride a white stallion. Hence the title. I was worried about the editors’ take on my choice of title and they did change it. But just a bit. I submitted Salami and a White horse. They changed it to Salami and the White Horse. Imagine if I published the book in a scratch-n-sniff format, like one of those children’s books. Garlic and horse manure.

AM: Yes, except I imagine the manure of a prince’s white horse doesn’t have much smell. What about your shift from the fiction of the novel and short stories to non-fiction?

KL: That was an eye-opener. Because I want all my writing to be realistic and credible, I spend more time researching and fact-checking than actually writing. With the first two books, if there were gaps in my research or I had written myself into a corner, all I had to do was create filler for the gaps or write a door to open to get me out of the corner. But with non-fiction–at least by my own self-imposed rules–I did not have the option of creating filler or doors. So, the salami book has a gap or two–such as why did a Vietnamese general vote to censure himself? I could not find the answer to that. Finding myself in an awkward corner that I couldn’t write myself out of was just something I had to live with, embarrassing or not. I’ve heard that the difference between fiction and non-fiction writers is that non-fiction writers keep the names and dates the same but change everything else for the sake of their writing. I won’t play that game. If you’re writing non-fiction, write the facts and let the gaps and cracks show. I won’t describe impossible dreams as facts.

AM: Salami is an intimately revealing book. Was it hard for you?

KL: Yes. But it probably saved me several thousands in psychotherapy. As I did my research, especially my family’s history and looking at family dynamics, I realized I was turning a hero into a jerk, respect into disrespect, and strength into fragility. With the help of my sisters and nephew, I was digging through family history, turning over long forgotten rocks as buried memories and emotions squiggled into the light. Midway through the book I started referring to my eldest son by my brother’s name and vice versa. Freud would have a good time with that one. In the words of one of my sisters, “This is like pulling off scabs.”

AM: Why didn’t you just stop?

KL: I did. Several times. Obviously, I restarted one more time than I stopped or this would be one boring interview. When I decided to try writing several years ago, I realized I was sticking my rear end and ego out the window and asking everyone to take a shot. If I didn’t want to take that risk, I’d better not write. When you ignore both the safety of your ass and your ego, you can keep on writing.

AM: Both you and your brother went into the military and to war. In Salami and the White Horse you describe being raised in a crucible of family patriotism. Do you think your brother’s early death was due to his war time experience?

KL: No. I’ve asked that question of several doctors. No bullets, no shrapnel, no parasites, no Agent Orange.

AM: You were twice wounded and exposed to Agent Orange. Are you bitter?

KL: No, I’m not. I was doing the job I wanted to do. But today somewhere in Hanoi or PhuCuong sits a Vietnamese about my age and probably half my weight with a voodoo doll of me and a bunch of rusty pins. He’s sticking these into the doll and saying, “Levin, you son of a b#*@! You came over here to kill me and my people then went back to your cars and super markets and big-busted women. But you can’t really leave.” Then he sticks a few more pins into the doll. If I ever get my hands on that guy, I know where I’m going to shove that doll. But I’m not bitter.

AM: Not going to buy him a beer?

KL: Robin, I probably would. Comrade in arms, that sort of thing. There’s a terrible irony to this. I was blown up and shot by weapons made in Vietnam or China or Russia and fired at me by the guys I was trying to kill. Those wounds have healed and scarred over. My good life went on despite the wounds. But the most prevailing physical pain and limitations in my life are not from those bullets and explosives and shrapnel. They’re from the after effects of Agent Orange, the defoliant made in America and used by Americans – not the Vietnamese we were fighting. We did it to ourselves.

AM: When you wrote Crazy Razor you modeled the character of a North Vietnamese female doctor after a woman doctor you found in your research on the Ho Chi Minh Trail. Five years later, in writing Salami and the White Horse you discovered that very doctor’s diaries. If you had access to the diaries when you wrote Crazy Razor, would the woman doctor on the Ho Chi Minh Trail be a different character?

KL: Yes, I would have written a character more like the actual doctor. The character I did write, however, is one of my favorite creations in Crazy Razor and I would have lost her. Fortunately, I did not discover the diaries until long after the first book was published. Crazy Razor is better for that.

AM: You’ve compared the first and last entries of your brother’s diary to the Vietnamese woman’s diaries. Talk about that, please.

KL: Sure. Two docs at war. In my brother’s diary, the last entry is written in Hong Kong on his way out of Vietnam to start civilian life with his family and begin his medical residency. He complains that the lousy weather in Hong Kong is not letting him shop for souvenirs. He lives for another decade. The woman doctor’s last entry tells of her waiting to be evacuated by North Vietnamese soldiers while American soldiers search for her clinic. Two days later, she is killed by an American bullet. In my brother’s first entry, he complains about the delay in delivering his foot locker and he doesn’t have enough fresh socks. She describes in her first entry operating on a soldier’s gut with only Novocain for an anesthetic.

AM: The very last chapter of Salami and the White Horse is a short two paragraphs. You describe a conversation after the French defeat in Vietnam between a French and Viet Minh officer. Why did you do that?

KL: The Viet Minh tells the Frenchman that the weapon he feared most during their war was a doctor who would treat the peasants and villagers without regard to their politics or nationality. He didn’t fear bombs or napalm or bullets. Maybe if instead of sending troops down the Ho Chi Minh Trail or putting US marines and soldiers and sailors and airmen in-country, or blockading sea-lanes and bombing, and both sides instead sent care givers – doctors, nurses and teachers – there would be no wall in Washington DC with nearly 60,000 dead American names chiseled in that smooth, beautiful, black marble. Maybe. Maybe not. Probably not.

AM: And finally, you put your cousin’s Lokshen Kugel recipe in the Glossary. Why?

KL: Three reasons. One, it’s mentioned in the book. Two, it’s really good. And three, why not?

Kenneth Levin is a decorated naval officer, twice wounded and retired due to blindness. Salami and the White Horse as well as Levin’s other two works, are available on Amazon, BarnesandNoble.com and on his website, BlindmansPress.com.

Leave a Reply