|

|

Workplace safety has always been very important to us here in the United States. When visiting a production facility invariably one will see a sign stating the number of days since the last accident. On construction sites we expect to see workers’ heads well covered with colorful hard hats. Most everywhere we turn we are bombarded with safety slogans and little reminders to be careful.

A number of years ago the government made safety an overriding goal by establishing the Occupational Safety and Health Administration which operates under the acronym of OSHA. Admittedly we joke a bit about this group, but it does serve as a watchdog on safety matters.

So where is all of this going? Well, while browsing through a pile of old trip photos I came across a number of pictures that point out our view of safety regulations is quite different from those practiced in many other countries. Let’s take a look at a few.

|

|

Probably the sites that demonstrate the greatest diversity between the United States and some foreign countries are their multi-story construction projects in Southeast Asia. Here in countries like Malaysia, Vietnam, and most of Indonesia, bamboo is used to form scaffolding on which hod carriers bring cement to those who are laying the brick. Now I’m sure bamboo is sturdy and stout, but when it is joined to another similar pole with a foot long piece of rope, it certainly can’t be trusted. Two, three, sometimes four stories or higher these flimsy bamboo scaffolds snake up the sides of construction projects. I’m sure you’ve seen a few yourself. Invariably they are irregular and angle out one way or another. I find myself mesmerized watching bare-footed laborers lugging cement in buckets along these swaying paths. I keep waiting for the entire structure to collapse and bring the whole project down with it.

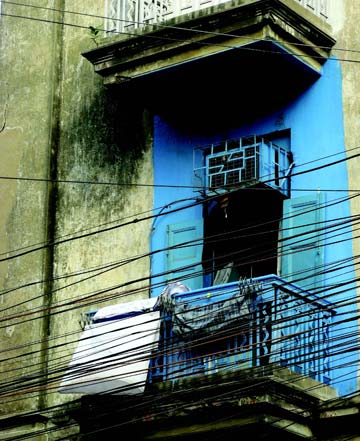

Another site which would drive OSHA into a fit of frustration is the electrical distribution cables which run willy-nilly overhead in many of these nations. I was particularly amazed while staring down some side streets in Old Delhi, India. Here, crisscrossing the streets, are hundreds of cables just sort of hanging there. Apparently if you want electricity you simply grab one of these lines and sort of tap into them with your own wires. I would suspect several hundred electrocutions per year could be considered average in this casual-use pattern. I did notice a few lines which just hung there, and I assumed they represented failed connections.

Again it’s hard to argue against success, but I advise any OSHA reader of mine to avoid these spots as they could certainly cause a psychotic response and might be difficult to forget.

Bamboo scaffolding and uncharted electrical grids may be the most obvious OSHA regulation violations, but there are others.

While visiting the Santiago Volcano site in Nicaragua, I was warned to stay away from the several hundred foot drop into the churning lava flows by a sign which read, “Stay behind the fence.” Now the thought was there, but unfortunately the fence had slowly migrated down the steep precipice until it was on its way into the cauldron itself. A visitor who took the sign seriously would have needed a rope and grappling hook to get to this rickety wood structure. I’m not sure just how old the sign and the fence were, but the location certainly badly needed an update.

|

|

One other sign violation occurred in Indonesia. Barb and I took an old, very beat-up ferry between Singapore and Sumatra. Posted in the main cabin was a sign which restricted the ferry’s occupants to one hundred and twenty people. Now I’m sure ninety per cent of the time the owners would love to have had one hundred and twenty paying participants. However, on certain holidays and other particular times of the year they easily make up for their shortfalls by loading these boats down with as many bodies as possible. This was one of those “particular times.” We found ourselves squished into the cabin with absolutely no chance of escape – hoping against hope that “the little engine that could” would make it across the Singapore Strait. Passengers were sitting on the floor, on the laps of other people, and standing on any vacant square of cabin floor. Escape was no option for us in case of any disaster, nor for the over two hundred and fifty crammed aboard.

The last story tickles me to this day. Admittedly we go back to the mid-eighties on a flight between Guilin and Shanghai, China. We stopped to refuel our jet at an ex-military air base somewhere between these two cities. The plane came to a stop at the end of the runway, and they requested that we all deplane. Here, in no-man’s land, stood over one hundred passengers while a truck came zooming out with hoses flying. It pulled up to the plane and a half dozen maintenance workers began pumping gas into the plane’s fuel tanks. I noticed one of the workers had a lit cigarette which was dangling from his lips. I grabbed Barb, and we retreated to a safer spot, about one hundred yards from the refueling site. It took about twenty minutes to fill the tanks of our plane, and then we were all hustled back inside. I’m sure this oversight has since been remedied, but I still chuckle to think of those maintenance guys puffing away around high-octane fuel. We could have been launched into orbit any second – all one hundred of us.