My Personal Experience with The Confederates

In 2011 our family gathered in New Orleans for my niece’s graduation from Tulane University Medical School. The ceremony was extraordinary; Pulitzer prize-winning author and columnist Thomas Friedman gave the keynote address, and singer-composer Stevie Wonder provided the entertainment. It was quite an evening.

Never having been to New Orleans before, we spent the next several days touring the city and surrounding areas. We did some of the obligatory touristy things like strolling down Bourbon Street and taking an airboat ride to see gators in the wild. We ate, drank, and danced to Zydeco, celebrating with family and strangers who felt like family.

I loved New Orleans—the food, the people, the architecture, the music, and most of all, the city’s laid-back, friendly, “non-PC” vibe. After all, I had never been to a city where you might encounter someone enjoying a mint julep while walking down the sidewalk at four o’clock in the afternoon. And when I say, “not PC,” I mean cigar smoking was still allowed in public places.

This was “The South”—a world apart from California and the San Francisco Bay Area’s hustle and bustle to which I was accustomed. When we were there, as far as I could tell, the heart of the city did not include an Apple store, as the charm and style of New Orleans harkened back to another time. And that was what I found most appealing and interesting. It was the city’s history, and by extension, its effect upon the history of our great country, that captured my attention most.

Despite all the fascinating attractions of New Orleans, there were three things that drew my attention and curiosity like a magnet to iron.

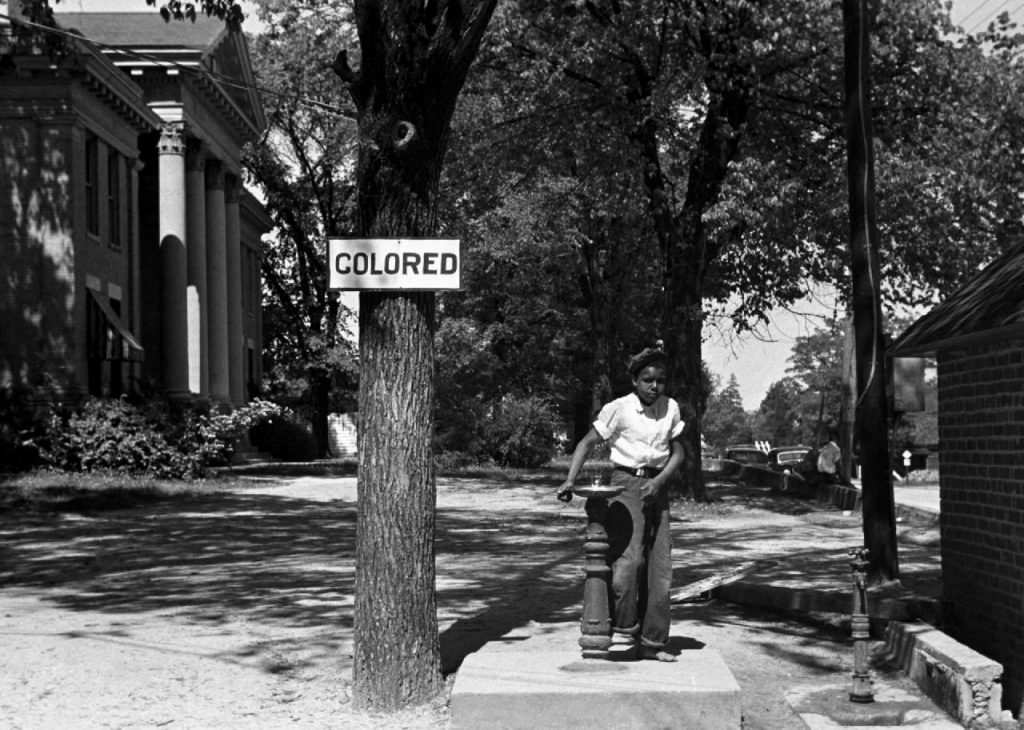

The first was a Slavery Museum in the French Quarter. Inside were items in display cases bringing the abject cruelty of human bondage into undeniable, absolute focus, There were things like wrist and ankle shackles that had once chaffed the skin of some long-forgotten human being—a person—likely “used” as a beast of burden. And there were paper receipts indicating the sex, approximate age, work-capability (as in, “a strong young male suited for heavy labor”), and the price asked and/or paid for said “property.” I had never seen anything like this in my life, and had no idea that a museum like this even existed.

Next was another museum—The Confederate Memorial Hall Civil War Museum. As stated on their website, the museum “opened its doors in New Orleans on January 8, 1891, and has been commemorating southern heritage and history for over 120 years. The museum is the oldest in Louisiana and houses one of the largest collections of Confederate memorabilia in the United States.”

The collection of rare, fragile material of historical importance was impressive. There were uniforms, flags, pistols and rifles, documents, and photographs. A dress uniform worn by General Thomas Jonathan “Stonewall” Jackson’s was on display, complete with dress saber and scabbard, as well as the riding saddle of Confederate President Jefferson Davis. In my mind, Stonewall Jackson must have been a physically imposing figure, but seeing his uniform said otherwise. While he was six feet tall, the narrow shoulders and slenderness of his uniform told me he was very slight of build. In fact, while I don’t intend to be sexist, I would describe his jacket size as being a “woman’s petite.”

One piece on display that will forever be seared in my memory was of what I would estimate to be a six or seven-foot section of a tree trunk, coated in some type of varnish to preserve it. It was just standing in the corner of one of the rooms in the museum. Embedded in the tree were several balls of “grape shot,” each about three inches or so in diameter. Seeing those lead balls securely embedded in the tree due to the force of cannon fire said everything one needs to understand about the carnage suffered by soldiers serving on both sides during the Civil War.

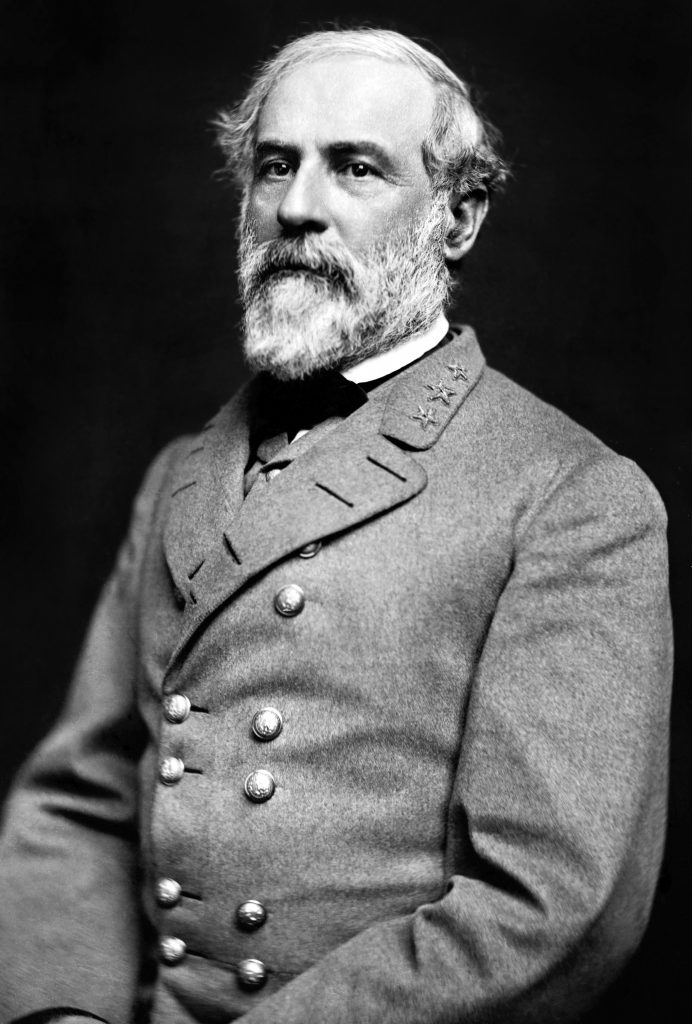

The final item of interest was a large statue of General Robert E. Lee that stood atop a sixty-foot column in the center of “Lee’s Circle.” The statue was erected and dedicated in 1884, only to be removed in 2017 after previous Confederate statue-related violence had erupted in Charlottesville, Virginia, earlier that year.

Times Change, Ideas Change, People Change

So what is my point in telling you all of this? My point is that by visiting these museums and monuments—be seeing them with my own eyes, and by touching and experiencing them—I was inspired to learn more about one of the most important periods in our nation’s history. Were Southerners just some kind of anomaly, a perverse, corrupt, evil strain of humankind, as many today seem to believe? Or were the romanticized images of “noble and chivalrous” Southerners anchored in reality? I wanted to know. Who were the Confederates? What did they believe? What was their “cause”—one they thought worth dying for?

At the time, while I already had a fair knowledge—or so I thought—about the Civil War, I became committed to learning as much as I could in trying to answer these questions. I read everything I could get my hands on, amassing a substantial library in the process.

Had those monuments and statues not existed, I would have remained in a state or relative ignorance about one of the most important periods of American history–warts and all.

But I did see them, and the result was, I learned a lot. First off, the world was a very different place then, as were the beliefs and values of everyone. In fact, the one thing that has not changed is that the entire story of America, and indeed of all civilizations, is that ideas and values do change over time. What most 21st Century Americans view as repugnant today was widely accepted as standard behavior prior to the Civil War.

For example, Abraham Lincoln wasn’t an abolitionist, and he didn’t believe blacks should have the same rights as whites. In one of the Lincoln-Douglas debates in 1858, Lincoln said, “I will say then that I am not, nor ever have been, in favor of bringing about in any way the social and political equality of the white and black races…” And, the Emancipation Proclamation was primarily devised as a military strategy to help win the war, as it originally only applied to slaves in most of the Confederacy. The proclamation did not apply to border slave states that had remained part of the Union, like Delaware, Maryland, Kentucky, and Missouri. Lincoln’s views on racial equality did evolve over time, but certainly not to the level where Americans and most of the world are today.

Does this mean Lincoln was just another evil racist white man? Taken out of the context of history, I have no doubt some with ill-intended political objectives would answer, “yes.” But that is not only wrong, it is unjust on its face.

For example, if someone made the argument in 1940 that “a woman’s place is in the home,” I’d bet that not only 100% of men but also 95% of women would have agreed. And in 1955, if you asked one hundred tenured professors in psychology or psychiatry to explain homosexuality, about that same percentage would say that “it’s a form of mental illness.”

Today we might say those ways of thinking were bad or evil or flawed, but that would be projecting our values and understandings into another time, and that is an exercise in futility with no relevance or meaning for our lives today or into the future. To my way of thinking, judging our ancestors in this way only serves to satisfy a perverse need some have to do the very thing they rail against—to classify others as being somehow “inferior” to them.

As distasteful as it is today, in early America, and long before, throughout much of the world, black people were believed to be inferior beings. Even in the African continent, some tribes believed other tribe members to be inferior. This was the way the world was, going back thousands of years.

Are there still pockets of this kind of backward thinking? Certainly, there are. But as time has progressed, this way of thinking and believing has become rarer and rarer, particularly here in America. While there may be anecdotal examples of racial bias from one person to another, gone are the days of widespread racial injustice in America, and I would challenge anyone to prove otherwise.

Why Were Confederate Statues Allowed After the Civil War?

Throughout history, during protracted periods of war, it is not uncommon for warriors of the opposing sides to develop respect for one another. In fact, during the Civil War, there are numerous stories of times when truces were enacted on certain common holidays, when soldiers not only ceased their fighting, but came together in celebration, only to return to battle hours later, oftentimes fighting to the death.

And when wars were won, what did Americans do to their vanquished enemies? Americans have always sought, and seek still, to help heal their enemies’ wounds and move forward into a hopeful future, not only in peace, but in cooperation. We build. We reconstruct. We do all we can to help past enemies make the often-painful transition from being a beaten, vanquished foe, into a respected member of a new society.

The process of healing the enormous wounds inflicted by the Civil War began logically by according a measure of respect to the humiliated Confederates. They were soundly beaten militarily and subsequently surrendered, so the best way to engender a lasting peace and harmonious future together was to permit them a sense of honor and grant them a modicum of respect due a worthy opponent.

Confederate veterans were recognized as legitimate soldiers and allowed to retire in peace, rather than as traitors deserving to be hanged. Organizations like the Confederate Veterans, the United Daughters of the Confederacy, and Sons of Confederate Veterans were formed, and Confederate graves were and are honored still, in places like Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia. Monuments and statues were erected throughout the South, recognizing Confederate leaders like Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson.

All of this was allowed in the spirit of healing and reconciliation.

The Transition to “Southern Pride”

In time, the reputation and status of Confederate soldiers and Southern culture grew and was embellished. The South was romanticized, becoming a kind of caricature of a culture; a blend of fact and fiction that scarcely acknowledged the foundation of the divide that was the issue of slavery.

The Confederate Battle Flag became a symbol, not of oppression, but of the independent spirit—of the rebellious quality of character that refuses to be controlled by others. This is the underlying sentiment of those who today speak of “Southern Pride.” This is also why they cling to their memorialized heroes. Allowing that Southern Pride to exist was never intended to be hurtful to the African American descendants of slaves, it was allowed in the effort to heal the entire nation—black and white.

Confederate soldiers and their leaders were historically viewed in terms of their courage and military acumen, and how they treated those who served under their command. General Lee, in these regards, was, and is still, considered one of the finest military generals in “American” history.

In terms of Lee’s character, it is significant to note that Lee rejected Lincoln’s offer to lead the entire Union Armies, because he could not bear to take up arms against his home state. He chose instead to remain loyal to his neighbors, family, and friends—to his homeland, the state of Virginia. The issue of slavery, or whether blacks should be considered equal to whites, had no bearing upon his difficult decision regarding loyalty and service. Here, in a letter to his sister, are his own words telling why and how he came his decision to join the Confederacy:

My Dear Sister,

I am grieved at my inability to see you… I have been waiting for a “more convenient season,” which has brought before many before me deep and lasting regret. Now we are in a state of war which will yield to nothing. The whole South is in a state of revolution, into which Virginia, after a long struggle, has been drawn; and though I recognize no necessity for this state of things, and would have foreborne and pleaded to the end for redress of grievances, real or supposed, yet in my own person, I had to meet the question whether I should take part against my native state.

With all my devotion to the Union and the feeling of loyalty and duty of an American citizen, I have not been able to make up my mind to raise my hand against my relatives, my children, my home. I have, therefore, resigned my commission in the army, and save in the defense of my native state, with the sincere hope that my poor services may never be needed, I hope I may never be called on to draw my sword.

I know you will blame me; but you must think as kindly of me as you can and believe that I have endeavored to do what I thought right. To show you the feeling and struggle it has cost me, I send you a copy of the letter of resignation. I have not time for more.

May God guard and protect you and yours and shower upon you everlasting blessings, is the prayer of your devoted brother.

Robert E. Lee to Anne R. Marshall [sister], April 20, 1861, Arlington, Virginia

It is clear that Lee had no intention of fighting against the Union, but as a man of his word, he became duty-bound to serve the Confederacy, nonetheless. When Union forces took to invading his homeland, he did what he had hoped not to do—he drew his sword to defend it.

The Foolishness of Destroying Monuments & Statues

Today, we see statues being torn down and vandalized, along with Confederate flags and other historical artifacts. In fact, anything even remotely associated with the Confederacy, the Civil War, the antebellum South, or America’s slave-related history, is being branded as something that must be destroyed. Some people claim they find these historical items offensive or disturbing because they see them as “symbols of oppression,” or as evidence of “systemic racism,” and there is a movement afoot demanding that these reminders of the past be erased.

Everything must go! Statues or monuments honoring Christopher Columbus, George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, along with another ten U.S. presidents, including Ulysses S. Grant, who led the fight of the Union forces that defeated the Confederates, must now be cast into the fire. Monticello, the Washington Monument, and now even Mount Rushmore, are all at risk of this zealous cleansing movement.

This entire movement, currently spearheaded by Black Lives Matter, is made up of people who choose to view our nation’s—and the world’s—history, solely through a myopic lens that recognizes only the failures in judgment and character flaws in our collective past. Never once do they stop and consider their own character flaws and failures in judgment. And the irony here is, these are the only things that truly impact their “today and tomorrows.”

On President Lincoln’s second day in office, he spoke to a delegation from Pennsylvania, saying that he wanted to spread the idea “that we may not, like the Pharisees, set ourselves up to be better than other people.” Apparently, this wise advice has yet to make its way into the thick skulls of our modern-day warriors of “social justice.”

The tragedy in all of this is in what it reveals about some Americans today. Their ignorance of history and, more importantly, of human nature, is astounding. It speaks of incredible immaturity and a colossal failure on the part of parents, teachers, and societal leaders. These are not adults with a measure of wisdom and life experience to know that human beings, past or present, were and are not one-dimensional creatures. No one, past or present, is either “purely good and virtuous,” or “purely evil and bad.”

How to Move Foward

When our country began to convulse after the tragic death of George Floyd, one of my best friends, an African American woman in her 30s who lives in Los Angeles, said to me, “What’s wrong with these people? This isn’t 1960 anymore; it’s 2020. Blacks can do anything they want today.” That was a true statement made by a wise, adult woman.

We all have ancestors and our particular family history. Some of it is good, and some is bad. Our job in the present is to accept it for what it was. We must acknowledge that our ancestors were not perfect, just as we are not prefect. Then, we are to do our best to learn from the mistakes of the past and move forward together.

As for the actual statues and monuments themselves, under no condition should they be destroyed or defaced in any way. Rational discussions about their appropriate placement is fine, but the adults in our society must stand up and make sure this is the course taken. And the children who believe they are “in charge,” or that their tantrums will force their way—they are in dire need of a firm hand by those adults. I plead to our wiser elders: please, don’t fail these children in their time of greatest need.

A Word About Slavery

Gauging by the actions and reactions of many today, one would think slavery was invented by white southerners. The only thing more striking about this than the ignorance of it, is the hypocrisy. Insofar as ignorance is concerned, anyone with even so much as a cursory interest in world history can tell you that the institution of slavery is about as old as civilization itself, and at one time or another it has infected every race, culture, society, and continent on planet Earth.

As for hypocrisy, people seem to think it only some a relic of a tarnished history, but it is alive and well still. In fact, as I write this, a prominent socialite named Ghislaine Maxwell sits in a jail cell awaiting charges for abuse of minors and sex trafficking, aka slavery, and there will be hundreds, if not thousands, of human lives ended and discarded because they were deemed “less than human” under the banner of “freedom of choice.”

“Ah, but the Supreme Court ruled in Roe v Wade that abortion is ‘legal’,” you argue. Okay, by that logic, where does the Supreme Court’s decision in the Dred Scott case lead us? The foundations for both cases are rooted in devaluing certain “classes” of people. In one case, race was the determining factor justifying blatant discrimination, in the other, it is a person’s “stage of development.”

Even aside from the abortion issue, men, women, and children are “trafficked” and exploited all over the world, every day.

One suggestion for those so outraged by the deeds of others long dead and incapable of defending themselves: How about focusing on the problems of slavery throughout the world, today?

And finally, what about trying to see America’s slavery-tarnished past in another light, in a way that helps build a positive future as opposed to just cursing the past? Maybe if more people could adopt African American writer Zora Neale Hurston’s attitude, we’d be further along. She said, “Slavery is the price I paid for civilization, and that is worth all I have paid through my ancestors for it.”

Leave a Reply